America is losing its sense of humor. Part of it can be blamed on a sensitivity clause. Nobody wants fun poked at them. People would rather see real life neighbors making fools of themselves in a reality show or on a home video clip than watch a movie that makes them reflect on their own behavior. Part of it is dimensional. The comedian is given two options; either be a bumbling, super empowered clown, or the cynical straight guy making cryptic observations about his household of fools. Either way, the funny is accompanied by props.

America’s first cinema funny man remains the king of comedy; Charlie Chaplin. He committed his humor without props, without stunt men, without even dialog, other than the painted words of silent films. In front of your eyes, he became an unscrupulous young man who snatched purses, lied about his financial status, who instigated fights, than left just before the police came to break things up. He became all the things we don’t laugh at today, because America doesn’t see them as funny.

Neither would America see the antics of the Marx brothers as very funny. Early cinema steamed with vaudeville humor. Prohibition was in full swing, and the stage was a glimpse into smoky dins of loose women and illicit activities. Groucho’s one-liners were back handed slaps at the appearance of common courtesy. Glibly, he tells a writer, “From the moment I picked up your book until I laid it down, I was convulsed with laughter. Some day I intend reading it.” Looking at the audience, he says, “I’ve had a perfectly wonderful evening, but this wasn’t it.” While Chico mangles words, uncovering unfathomable meanings, Zappo plays it straight; the mournful, misunderstood lady’s man made to look a fool by his unwitting brothers. Then there is Harpo, whose only communication is a horn he beeps liberally, and which is apparently an entitlement for entangling himself in the personal space of others. Of all the Marx brothers, the innocent escapades of Harpo would be the most taboo definition of humor today.

Neither would America see the antics of the Marx brothers as very funny. Early cinema steamed with vaudeville humor. Prohibition was in full swing, and the stage was a glimpse into smoky dins of loose women and illicit activities. Groucho’s one-liners were back handed slaps at the appearance of common courtesy. Glibly, he tells a writer, “From the moment I picked up your book until I laid it down, I was convulsed with laughter. Some day I intend reading it.” Looking at the audience, he says, “I’ve had a perfectly wonderful evening, but this wasn’t it.” While Chico mangles words, uncovering unfathomable meanings, Zappo plays it straight; the mournful, misunderstood lady’s man made to look a fool by his unwitting brothers. Then there is Harpo, whose only communication is a horn he beeps liberally, and which is apparently an entitlement for entangling himself in the personal space of others. Of all the Marx brothers, the innocent escapades of Harpo would be the most taboo definition of humor today.

By 1950, the era of television had begun playing a dominant role in viewing entertainment. A new type of humor was introduced; a wide-eyed, redheaded housewife concerned with the nightclub performances of her Cuban husband. Lucille Ball’s humor was unique for several reasons. Although a very pretty woman, she chose to quit her career as sexy blonde starlet for movies to play the role of a silly, inept housewife, star struck by the rich and famous. At a time when racism was an unconscious aspect of social life, it wasn’t her Cuban husband who bumbled through the rules of etiquette among the elite, but Lucy. Lucy wasn’t concerned about whether a camera angle made her look awkward, ungainly or plain. Her philosophy was, if it looked funny, shoot it. Her casual disdain for her looks opened the door to other inspiring, funny but not so very pretty women, such as Phyllis Diller and Lily Thomlin. Lucy, however, would probably be beating in vain at television producers’ doors right now because it just isn’t socially acceptable to make fun of housewives.

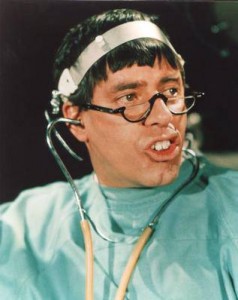

The nineteen fifty’s also heralded a change in the mood of American viewers. With the Great Depression and World War II out of the way, America became more light hearted. It became enthralled by Red Skelton, whose greatest gift was pantomime and Jerry Lewis, who explored the realm of ridiculous, stretching it to its limits with an amazing adeptness of changing at whim from a homely, myopic, mentally challenged, poorly dressed youngster, to a suave, smooth and very handsome man. Yet the most remarkable talent of all remained in a man who was quietly funny; whose reputation built slowly; as he delivered time and again, the elastic performance of someone who manages to always recuperate from falling down. Dick Van Dyke is probably the only stage performer whose agility reflected early Chaplain days. When considered for a role in Mary Poppins, he was asked if he could dance. He commented years later that he had never really thought about dancing before, but if he wanted the role, he had two weeks to learn. What he delivered was an unforgettable Bert, who wooed and won the hearts of America while whisking down chimneys, accompanying two children on their amazing adventures, and courting the mystical nanny of his dreams, Mary Poppins.

Dick Van Dyke, Jerry Lewis, Harpo Marx, Lucille Ball, Charlie Chaplain, Red Skelton, all had one thing in common; they used their body language, their facial expressions, their elasticity to deliver funny. It’s not the proper way to be funny anymore. There is no need for contortionists as stunt people and graphics will do the job. A falling down scene doesn’t quite compare with jumping from an airplane at ten thousand feet, landing in a garbage dump piled high with dirty mattresses, and rolling out of the way of twenty-five Ninja fighters. The most necessary requirement for the funny role is having the right face.

The period between the nineteen sixty’s and nineteen seventies could be called, in media terms, the age of awareness. Light humor was slowly being replaced by thoughtful, social humor. *MASH* paved the way. First aired in 1970, at a time when the morality of war was being questioned, Mash captured the imagination of both military and non-military audiences alike. It’s neutral background as an emergency medical unit on the war front, allowed the show to explore ethical dilemmas from a humorous view, and produce a rangeof personalities from the fervant flag waver to poor Klinger, who tries every ruse under the sun to get a medical discharge. In 1971, All in the Family rocked America by presenting the most politically incorrect character of all time, Archie Bunker. His narrow, chauvinistic, racist perspective reflected a wide spread view that began to feel silly as civil liberties began to mature in liberal America’s mind. Redd Fox, making his statements first in nightclubs and in audio tapes that could only be found in the adult section, cleaned up his language and made his debut in 1972 as a junkyard owner/ bereaved widower, tyrannically trying to control his son whose main concern is becoming a successful business man in a competitive world. His funny as a black man was actually the comedy of an everyday man, bypassing any true identification of color.

The funny person was being replaced by the funny show, settling into dark humor. The media attempts to lighten up produced a flurry of situational comedies, in which families bumbled through their mistakes, neighbors produced their irritants, children said charming but precocious things and aliens had the best lines. With the exception of Robin Williams, whose career carried him where no other schizophrenic personality has gone before, the days of the funny person were over.

Good comedy is a skill, as much dependent on delivery as it is on dialog. It’s wasted on graphic over-expression, on timid acting skills whose greatest concern is that they present a commercially engaging image. It’s lost among a public that will commit any stupidity just for the chance to earn a moment of fame. It’s painfully lost when the viewers will laugh at the completely unbelievable, but will not laugh at themselves.

This is the great motivating factor of good comedy. We all have to look in the mirror once in awhile and face the sillier depths of our personalities; our pomposity, our vanities, our lingering prejudices, our unwillingness to face change. They are the normal aspects of the human condition, a reminder that as much as we might strive for flawlessness, there is always room for improvement. Once we see the comedic value of our flaws, they are no longer quite so relevant. We can laugh at them. We can challenge them to change.

Because of its therapeutic value in regaining perspective, humor is often found in areas devastated with hardships or in the wake of a calamity. After the 1964 earthquake that destroyed large areas of Anchorage, Alaska, jokes bounced around about living on the wrong side of the crack and new waterfront property owners. After several years of economic poverty that severely effected the public diet, a favorite greeting during the Mexico City peso crash was, “I see you very fat to be dead and very thin to be alive”. Humor, whether dark or silly, helps people make it through the hard times.

These are hard times, but they are no worst than the historic day when the first black and white silent movie flickered across the screen and captivated an audience with the antics of a strange little man with an oversized mustache, a cane and a peculiar up and down gait that became a trademark. Despite the exhausting grind of the Great Depression, the bitter campaign of prohibition, the trauma of war, people gathered and payed their quarters to communally watch the parodies of drunkenness, unrefined manners, trouble makers and scam artists as portrayed by Charlie Chaplain. They watched, seeing the vexations of real life exaggerated into comedy and they laughed, relieved that they could finally let go of some of their anger and frustration. They laughed because Charlie was funny.

The comedian of today stands before a live audience, hoping the cameras will somehow find him or her to Comedy Central. The popularity is shifted here and there as some make it into recorded sessions and others become one shot wonders. Their names are diligently pronounced by in the know comedy watchers, and soon forgotten with the newest rave. Social commentary comedy is more openly expressed in cartoons than in the pantomimes of a comedian. The straight man/ funny man routine that brought to intense popularity such teams as Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin, Rowan and Martin, and the Smothers Brothers has been replaced by one-liners and puppet masters, their solo performances somewhat hollow in a world that relies on feedback. They are forgetting how to be the funny person, the one whose body language, facial expressions, odd little pauses and personality quirks announce, “this person is a comedian”. Nobody wants to be laughed at, not the deceivers or the achievers, the housewife or the business person, or even the comic face. But nobody wants to be the funny person, either, only the one with the best lines and best jokes.

I like to think the comedian is out there, the person who sees life from a little lighter perspective and shares a gift of laughter with others; perhaps in a steamy bar room, perhaps holding concerts in a park, perhaps exciting children into shouts of laughter. I like to think the comedian will return to grace our cinema with a commitment to being funny. It’s a vicious atmosphere, however. Tickets were refunded at the 92 Street Y when the audience felt comedian Steve Martin, did not live up to their standard of excellence during a performance. We’ve chosen what is accepted as humor. We’ve defined the parameters of a good laugh, but in doing it, we’ve forgotten how to appreciate what’s funny.

What a great article, Karla! Very astute observations about comedy today. There are funny thing at the movies and on TV, but as you say, it’s not really about “funny people” anymore. It’s all very manufactured and peer oriented. You’re only funny if you pander to the lowest common denominator. You’re only funny if you have attitude or if you’re controversial. And of course, cartoons, the funniest things on TV are social commentaries. Look at the sitcoms day…most of them don’t even have laugh tracks! The joy of performing and being “silly” is gone.

The art of funny is gone. Everything is filtered today through political correctness or anti-political correctness that makes a sitcom crass (but not necessarily that smart). Personally, I think Seinfeld was the last true comedy show of our generation. It is the “music video” that killed the radio star. It combined the bumbling world of slapstick and fused it with ironic cynicism of dialogue. Now, everything tries to be Seinfeld but misses the point entirely. Thanks for the memories.

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Amit Sodha and Amie_crs, Late Mitchell Warren. Late Mitchell Warren said: Great article by Subversify's Karla Fetrow on the dying art of comedy. http://subversify.com/2010/12/03/the-dying-art-of-comedy/ […]

Comedy was alive and kickin’ on British TV long after its de facto extinction in the US. And British comedy such as “Yes Minister”, “Porridge” or “Fawlty Towers” would beat most American “comedies” hollow…except for Lucy, who remains the greatest comedienne ever.

Bill, we used to receive a lot of BBC broadcasting, and you’re right. The English comedy i remember was absolutely delightful. However, BBC has been phased out a lot from the American diet, so in the field of media entertainment, we are completely deprived. Master comedians like Lucille Ball and Charlie Chaplain are few and far between. We were lucky they came to their height while film making was in its pioneering stages, or we might not have known about them at all.

Mitch, Seinfield himself, got on my nerves a bit because he reminded me of people i have known who i never found very pleasant. However, Kramer saved him. Kramer was the true comedian. Kramer was everything you would expect from a comic artist and i think it a shame that he never expanded past Seinfield.

I think one of the problems with comedy these days is that it’s almost become franchised in a way. There are so many outlets for being viewed that once a piece is found to be popular, the tendency is to beat that into the ground until the public moves on.

I believe that comedy is alive and well if one knows where to look. Everything that was good about Seinfeld is alive and kicking in Curb Your Enthusiasm with Seinfeld creator Larry David delivering up social inneptness and saying out loud what we all want to say at one point or another.

For slapstick we can look to Always Sunny in Philadelphia where the cast is constantly making fun of themselves, social mores and nobody gets a pass.

If we look past Jack Blacks stupid script choices we can see someone who is highly skilled at physical comedy. I think he just needs the right script.

I would agree that we are lacking in female comedic roles but really besides Lucy how many females played something other than the straight man anyway?

No comedy is not dead. I believe it is our own collective sense of humor that is endangered. We inhibit ourselves from laughing at life.