It was the year 1885 when the government of Canada put Métis leader Louis Riel to death. To this day there still is a debate amongst Canadian scholars to whether or not Louis Riel was hung rightly. Personally, I just cannot fathom the academic fascination these scholars have on this particular subject, the man has been dead for well over a century – what does it matter what size his penis was or whether he dressed to the right or the left? The man had a noose thrown around his neck; shouldn’t that be the focus on whether he was guilty or innocent? Sorry but that, it’s just a very sensitive issue for us Canadian men – the rest of the world can’t understand the ramifications on the male ego when the Canadian government constantly reminds the other nations that the last hung guy in Canada died in 1968. The world cannot understand being in a night club talking to some hot woman who takes a glance downwards…the comments before walking away, “oh sorry, I didn’t realize you were Canadian”. It hurts, people, it hurts. Let us put aside the sexually deviant ponderings of academia and focus on the actions of Louis Riel: was he one of Canada’s heroes or was he just a shit-disturber, or as we Canadians refer to a hoser?

It was the year 1885 when the government of Canada put Métis leader Louis Riel to death. To this day there still is a debate amongst Canadian scholars to whether or not Louis Riel was hung rightly. Personally, I just cannot fathom the academic fascination these scholars have on this particular subject, the man has been dead for well over a century – what does it matter what size his penis was or whether he dressed to the right or the left? The man had a noose thrown around his neck; shouldn’t that be the focus on whether he was guilty or innocent? Sorry but that, it’s just a very sensitive issue for us Canadian men – the rest of the world can’t understand the ramifications on the male ego when the Canadian government constantly reminds the other nations that the last hung guy in Canada died in 1968. The world cannot understand being in a night club talking to some hot woman who takes a glance downwards…the comments before walking away, “oh sorry, I didn’t realize you were Canadian”. It hurts, people, it hurts. Let us put aside the sexually deviant ponderings of academia and focus on the actions of Louis Riel: was he one of Canada’s heroes or was he just a shit-disturber, or as we Canadians refer to a hoser?

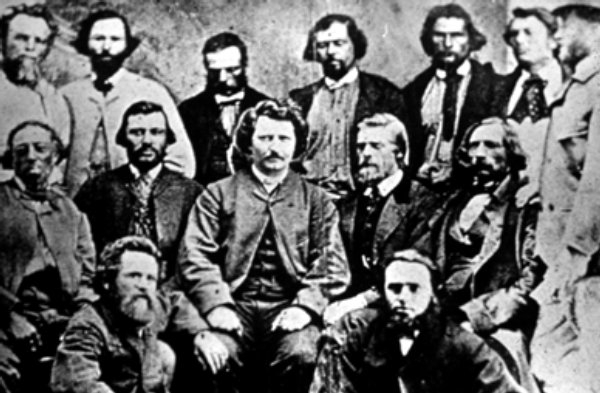

Louis Riel was born October 22, 1844 at the Red River Settlement; west of Ontario called Rupert’s Land; which would become later the province of Manitoba. Louis was what we Canadians call a Métis – half Native and Half French descent, not to be confused with Sit’em’s, which naturally would be half Native and Half English descent. At the time it was a tale of two Canadas one could say; with Ontario being primarily English and Protestant, while Quebec was French and Roman Catholic. The Red River area, with its large French and Métis population, followed this design as well. As a young man Louis was sent to Montreal to study for the priesthood. Though he never graduated, his foray into studying to become a lawyer ended similarly. While Riel did not formally graduate, he was considered well educated and was bilingual, by 1868 Riel would be back in the Red River area where he would quickly emerge as a leader for the Métis people.

In 1869 the Hudson Bay Company had agreed to transfer the Red River area and the North West area to Canada by the first of December. The government appointed William McDougall as lieutenant-governor of the territory. His first act was to send survey crews to Red River. This action lead to the Metis organizing a “National Committee” with Louis Riel as secretary, which halted the surveys and prevented McDougall from entering Red River, culminating in the seizure of the Hudson Bay Company’s Fort Gary on November second of that year. From the Métis point of view this was a rational exercise. The Red River area was still attempting to recover economically from a grasshopper infestation the year prior, there had been an influx of Anglo-Protestant immigrants from Ontario who were aggressively carving spots of their own and the American pressure to become part of their territory. It was decided that there had to be a form of governing rule in the vacuum created by the impending transfer that needed to be addressed. There should be two items of note about the action of commandeering Fort Garry: Firstly, there was no resistance from the Hudson Bay Company. Secondly the committee invited all the citizens of Red River to send delegates; English and French, Protestant and Catholic to Fort Garry for representation. The Canadian government, however, would see it as an act of rebellion.

The committee would then form a provisional government with Riel leading December twenty-third. Riel would issue the document entitled, “Declaration of the People of Rupert’s Land and the Northwest”. On January twenty sixth there would be a general meeting that not only included Riel and his associates but representatives of the Canadian Government and the Hudson Bay Company to debate Riel’s writing of the “List of Rights” that would precede Manitoba entering into the Confederation of Canada. This list included rights such as “That all people have the right to elect their own legislature”, “That English and French were to be commonly used by the government [sic]in all documents and Acts of the legislature” as well as “that all privileges, customs and usages existing at the time of transfer be respected”.

A group of transplanted loyalists, or Orangemen, originally from Ontario with ties to the strongly Anglo federal government saw Riel and the provisional government as an act of sedition and attempted to overthrow it. Faced with armed opposition, the Métis of Fort Garry were alarmed and quickly rounded them up as they were trying to enlist support from the Scottish parishes of Red River. One of the Orangemen, Thomas Scott who had come out to Red River as a surveyor, was caught and charged with treason . Scott would be executed by a firing squad on the fourth of March, 1870. Though it would be an associate of Riel, not Riel himself, that presided over the court-martial and sentencing, the Canadian government would hold Riel responsible for the actions.

Though loudly opposed by the Orange Lodges of Ontario that Scott had been a member of, Riel and his delegates obtained an agreement that would embody the Manitoba Act from the Canadian government that would pass in parliament May twelfth 1870. It would transfer power July fifteenth of that year, as well as 1,400,000 acres of land for the Métis. For his role in creating the Provisional Government, and for the death of Thomas Scott, Riel was labeled a traitor by then Prime Minister John. A. Macdonald though he was never officially charged. To show Ontario and support the new lieutentant-governor Archibald, the federal government sent a military force to Red River in the summer. Fearing that the military may not have been on a “mission of peace” as the government had said, Riel fled to the United States. He would return a few months later, and when the new province was threatened by a Fenian raid from the United States in the autumn of 1871, he would offer a cavalry force of Métis to the lieutenant-governor.

In 1873 Riel was successful in gaining a seat in Parliament through winning a by-election and then again in the general election of 1874. Riel went to Ottawa but was expelled from parliament on a motion introduced by the Ontario Orange leader Bowell. Although Riel was once again re-elected, he chose not to attempt to take his seat. By February of 1875, the Canadian government adopted a motion granting amnesty to Riel, conditional on a five year banishment from “Her Majesty’s dominions”; Riel made the decision to move to the United States.

Since he had left Canada he had gone into a depression with bouts of euphoria in which he began to talk of speaking with the “Divine Spirit” and that he was the “Prophet of the New World”. Riel suffered a nervous breakdown and friends smuggled him back into Quebec; to be first admitted into the Longue Pointe (or now known as Montreal) hospital, then to be transferred to a mental asylum in Beauport. It was while he was under psychological care that Riel chose to see his life as a religious mission; to establish a new North American Catholicism with the bishop of Montreal as the Pope of the New World and to see his Métis brothers and sisters as equal members of society. Riel was released in January 1878 and returned to the United States, first to New York, then settling in the Upper Missouri region of Montana where he joined the Republican Party, become an American citizen and took a wife.

Much like the conditions of the Red River settlement in 1969, the prairies had been going through political, economic and social disarray. There had been talk of the West forming a new country with Manitoba, the Northwest Territories and British Columbia, a scurvy epidemic that had run through the west in 1883 and 1884, and wide spread starvation. The Canadian government responded to calls for food by sending more police forces instead. June of 1884, a Métis delegation from the south branch of the Saskatchewan River sought out Riel, who was teaching as a school teacher for a year at the St. Peter’s Jesuit mission in Montana, asking him to represent them in obtaining rights for them in the Saskatchewan Valley. Riel agreed and by July he and his wife reached Batoche, the central Métis settlement in Saskatchewan.

Riel began speaking around the district as well as writing a petition. By that December the Canadian government promised would form a committee to investigate and report to parliament Western problems. Unlike in Red River, Riel found himself without a majority Métis population to back him, along with continued resentment over the execution of Thomas Scott, his personal claims against the Canadian government of approximately$35,000 and the general knowledge of his religious views that hampered political pressure to forward action by the Canadian government on the petition.

March nineteenth, 1885, Louis Riel and several Métis would take over the parish church in Batoche, form a provisional government and demand the surrender of Fort Carlton, setting off what was later referred to as the Northwest Rebellion. In a way, there is confusion as the actions of the Indian population and the actions of Riel and the Métis, as they were not combined but separate within the same time line. March twenty ninth, the Stoney Indians shot and killed a government teacher who refused to give them food for their starving tribe. A day later, the Cree who were in a similar position, raided the fort at Battleford. April second, nine whites were killed by Indians during a raid on Fort Pitt. The response by the Canadian government was swift; the railway that would link Eastern Canada to Western Canada was almost complete and the North-West Mounted Police, the precursor to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, were already established in the west.

This is not to say that there was not an armed section of the Métis resistance. There was one led by Gabriel Dumont, though it is said Riel made no attempt to interfere with the military aspects of the action. On March twenty sixth Dumont defeated a group lead by NWMP superintendent Crozier at Duck Lake just outside of Batoche. Métis forces would once again be victorious over government forces on the twenty fourth of April at Fish Creek. This would lead to where the Métis would make their final stand at Batoche.

On May ninth Major General Middleton’s forces laid siege to Batoche. With Middleton’s forces greatly out numbering the Métis, who quickly ran out of ammunition and resorted to firing sharp objects and small rocks from their guns, the battle lasted only three days. By May Fifteenth, the armies and police forces of Canada had put down the Indian resistance and Louis Riel, shoeless, surrendered himself to the police. Gabriel Dumont and several other Métis managed to escape and crossed the border into Montana.

On July sixth, 1885, a formal charge of high treason was laid against Riel with the two week trial beginning the twentieth of the same month in Regina. The jury found Riel guilty but recommended clemency. The verdict was appealed to both the Court of Queen’s Bench of Manitoba and to the Judicial Committee of the Privy council with both dismissing the appeals. There was public pressure to excuse Louis, especially from the pre-dominant Roman Catholic Quebec, delaying execution as three physicians examined Louis Riel’s mental state – all found Riel to be “excitable” but only one thought that he was insane. With the official version not revealing any difference of opinion among the physicians, the federal Cabinet decided that Louis Riel would face the consequences for his actions. It was just after 8:30 the morning of November 16th, 1885, Louis Riel’s feet swung limply beneath the trap door of the Regina gallows.

Hero or hoser, one cannot deny that Louis Riel has continued to be relevant in the twenty-first as he was in the nineteenth century. Delusional or defiant, he chose not to be indifferent. Depending on one’s heritage it could be debated whether Riel utilized a pair of forceps on the cresting head of Canada or attempted to use a rusty coat hanger as it emerged from the British womb. He attempted to protect not only “his” peoples but English, French, Native, Catholic and Protestant alike that resulted in Manitoba and in a way, Saskatchewan, becoming Canadian provinces. While violence surrounded him, it could be said that the violence was not directed by Riel but ran parallel with his intents. Did that make him a revolutionary just as the American “Minute Men” or indeed a traitor to Canada? Perhaps there is no true answer but his attempts make him one of Canada’s first subversives and that should be acknowledged for the value that label has.

What a fascinating piece of history, one that leaves you contemplating the entire saga of the Native American conversion. To me, it feels like he sacrificed himself willingly, knowing the probable chances of a dire outcome, yet determined to take chances anyway. So much of Canadian history reflects on the history of my own demographics. By the time white settlement reached Alaska, the “enlightened” person had managed to dismiss all overt signs of racism. The cultural invasion was relatively peaceful, probably because of Canada’s early efforts to create a balance. We also felt the influence of the Hudson Bay Trade Company, but that’s all for my own historical stories. Thank you very much for sharing this story that might help create a global understanding of America’s First People.

I’ll go with Hero and Hoser…who says you can’t be both? To me that really is the message left. One needs to step up to the plate in defence of what they believe.

Riel has always been a role model for me. He tried to do find solutions in the way that were expected yet he never gave up and moved onto actions that forced those who would ignore take heed. It decries of the injustice of our ‘equal’ society that now apathy has set in to where the people have yielded power to the system.

Great article and very timely for me as I have been studying the history of the fur trade. Thanks for a closer look into Metis’ history.

wow that is so cool

why did the stoney indians kill a government teacher i need to know i am so confused

if any on reads this pleez answer

thanx, Sarah

awesome

somebody pleez i am so desperate

why did the stoney indians kill a goverment teacher pleez pleez pleez

if somebody told me i would love you forever pleez pleez pleez

thanx, Sarah

the stoney indians killed a government teacher because he refused to gine them food to feed there starving tribe

i here you are desperate so am i

thanks but no thanks

now do one on the first biological weapon used to kill millions of first nation people. and then put one up on the first holocost to my people before hitler was even thought of.

This is a really debatable argument! I’ve to write an essay whether Riel was a hero or not and I’m super stumped. He’s a great person to look up to, but then if you look at it from a different point of view it then changes your opinion.

Riel was fed a big supper the night before he was hung. Why ? So he would poop himself, as though a further disgrace to other questionable acts.

Was Louis Riel a pain in the ass, or rather attractive to peolple like United States Congresswoman Jackie Speier, a Democrat Representative from California, who publicly supported the Taliban on MSNBC by saying that they were not “necessarily” terrorists. Her outrageous comments came during a discussion about the prisoner swap where President Obama freed 5 top level Taliban commanders in exchange for Army Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl ?

Nice to see my previous comment failed to get posted. Facts from Riel’s trial should have recieved equal treatment.