“Alex! The rope!!! Exhausted by the relentless heat of a sub-arctic summer and the aching glare of the river, my concentration lapsed for a moment. But that was all it took. Standing on the river bank, I could do nothing as the current caught my beautiful red canoe, snatching the lining rope out of my hands. For a long moment, she floated free but unsure, like a wild horse offered an open gate. Then, she swung broadside to the river, allowing a wave to swamp the kit. I was convinced it was all over, when Jean Pierre’s hand closed around the bow, hauling the canoe – and several gallons of water – from the river’s grasp in a single, Herculean movement.

“Remember,” he said laconically “To keep the rope tight.”

I wasn’t the first to almost lose my canoe like that on the Nascaupi River. Bizarrely, the explorer Mina Hubbard had a very similar experience here when she made her pioneering journey across the Labrador interior in eastern Canada in 1905. I was the first person to attempt her route since then – although I hadn’t planned such historic accuracy as to re-create her accidents, too.

Labrador, part of Newfoundland province, is a land of endless fir and spruce trees, high tundra and mighty rivers, where winter temperatures drop to minus 40 C and the short summer is a torture of mosquitoes and black fly. Mina’s achievement In becoming the first white person to travel across what was at the time, a ‘blank space’ on the map of North America, was all the more remarkable as her husband Leonidas, an American journalist, had famously died of starvation and exposure while attempting the same route two years previously.

I have always been attracted to wild places and so I was captivated by Mina’s story. Yet I also wanted to celebrate her achievements, which like so many other women explorers, have been allowed to sink from view.

My own experience in Labrador showed the magnitude of what Mina had achieved. Snow two weeks before our departure in July turned to a brief, but searing arctic summer. After paddling forty five miles across lakes, we turned upriver. Hot days were spent paddling through sluggish water and densely wooded riverbanks that turned into ever narrower channels where the river ran swift, the standing waves of rapids churning up the water.

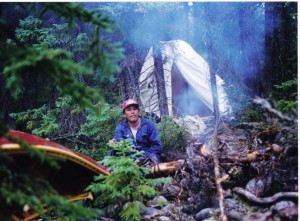

For days we inched our way north against the current, lining, poling and portaging around rapids, cutting trails through the trees when we couldn’t stay on the river. We survived a tent fire, two tornadoes and a thunderstorm, sheltering in the sweet-smelling cocoon of the upturned canoe as a double rainbow fell into dark forest on the opposite bank.

Eschewing some modern equipment (but keeping a satellite phone), I traveled in a cedarwood and canvas canoe, slept in a traditional canvas ‘Labrador’ tent and cooked on a woodburning stove, just as Mina had. We shared, too, some other uncanny co-incidences, such as losing our head nets on the same trail (although, unlike Mina, I didn’t resort to cutting eyeholes in a canvas bag and putting it over my head for protection from mosquitoes) and we both learned a great deal from our guides.

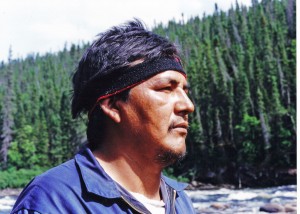

Where Mina travelled with four guides, I had only Jean Pierre Ashini, an Innu man who has spent most of his life following trails between the seasonal hunting grounds of his ancestors. It was his company that provided some of the strongest memories of my trip. Each evening we would relax in the tent, the ground neatly covered by sharp-scented spruce boughs, a citronella candle casting shadows on Jean Pierre as he rolled another cigarette.

“Tell me a story” I’d say and so he would, his voice low over the ever-present roar of the river, telling tales, old and new, of times when shamans battled and spirits ruled the land.

The passage of a hundred years has rendered those evenings more fascinating than daring. Yet Mina was one of the first women ever to travel alone in the company of Native men and she used those long hours in the firelight to learn about their lives and speak Cree, their language. Some critics at the time saw Mina as little more than a ‘mere passenger’. Yet this took no account of remarkable preparation and planning which kept all five in food and good health for eight weeks; of her responsibilities, including returning with scientific information and above all, her role as leader. As one guide, Gilbert Blake, said:

‘”We were never before on a trip where the women didn’t do as they were told.”

Mina may have taken her turn catching and gutting fish, happily giving chase to bears with her revolver and racing the canoes, but in her book, published in 1908, she portrays herself as feminine and without skill. In the drawing rooms of London and New York, she was fighting a PR war against Edwardian sensibilities. Her personal diaries however, tell a different story, one that is as much about her response to her guides and the landscape, as it is about the macho ideal of ‘uncharted territory’ (to the Native people of course, it was home).

In my book, I too raise questions about the fate of the Native peoples and their land in the past century. Labrador may have been the first part of Northern America to be seen by Europeans, but it has been the last to be developed. Long protected by its own ruggedness, it is the western world’s last true wilderness and integral to the traditional life of the Innu. Just one generation ago, they were ‘settled’ by the Canadian government into inadequate villages – one without running water – where alcoholism and suicide rates now soar.

The issue of who owns the land is a hot topic as Labrador is on the brink of industrialisation. This has picked up a pace since the 1970’s, once one of the worlds’ largest waterfalls was dammed, lowering water levels all over the upper plateaux and making our progress upriver far more difficult than Mina’s. Where once beaver dams were numerous, now the remains of temporary camps set up by mineral prospectors, dropped in by helicopter, scatter the riverbanks. Most resented of all by the Innu however, is the use of this unique landscape by NATO as training ground for low-flying jets, like the one that screamed over our peaceful camp one afternoon, the delayed noise as shattering as a baseball through the side of a fish tank.

Our journey didn’t take us as far as Mina. Faced with forest fires and injury, we were forced to turn back, but certain images will stay forever in my mind: The sun breaking through the clouds and touching the lake with silver, the distant boom of rapids, softened by miles of forest and the perfect stillness of a Labrador sunset. The wilderness can change perspectives in so many ways. Life becomes more elemental; rock, water and sky begin to press on one’s consciousness and the fragility of human survival becomes as clear as the quick running river itself.

My desire to follow Mina out into those hills was replaced with a desire to know the place and that became the real story; not in the rivers, mountains and valleys, but in the hearts and minds of the people and their connections to that ancient land. Labrador remains a place apart that has a power to captivate all who experience it, taking my journey and turning it into something much more interesting than a mere adventure story – one that I didn’t know myself until I paddled out into that wilderness.

Alexandra Pratt is a British journalist and author. The full story of her award winning canoe expedition to Labrador is told in ‘Lost Lands Forgotten Stories: A Woman’s Journey to the Heart of Labrador’, published by Eye Books 2005.www.alexandra-pratt.com

I think i need the full story. I was just settling down to read an account of some of Jean Pierre’s tales, and no account! Then you tell me you were faced with injury and wild fires, and what a story that must have been!

Freakin’ NATO. They’re sure not being very nice these days. Don’t they have something better to do; like i don’t know; writing peaceful treaties or something, rather than playing war games?

I too am heartily captivated and must search out your book. Thanks for this Alexandra.