Gory, terrifying, historically accurate, impeccably detailed, and absolutely true account of Rebel soldier’s experience during America’s Civil War. He survives thirteen battles in four major campaigns under Generals George Pickett and William Longstreet. Yet, our soldier’s worst fear is not of being shot but of the smart, ruthless wild hogs stalking both armies. He can see them on the mountains, in the thickets, at the edge of the woods, waiting patiently to eat the faces of the dead and wounded after darkness has covered the battlefields. Hess’ actual diary is included as an appendix, along with a complete bibliography.

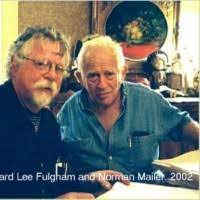

ENDORSED BY NORMAN MAILER! (author of “The Naked and the Dead” and thirty other award winning books. The late author won two Pulitizer Prizes and The National Book Award, making him one of the most significant and most read writers of the Twentieth Century. He endorsed Fulgham’s book after reading it in 2004.): “This book is a discovery. It gave me so close a sense of what it was like to be a Confederate soldier in the Civil War that I began to think of my own army experience. Old fears, old excitements, even memories of my old equipment, and with it all, vivid as the sound of gunfire, came the smell of battle in the air of the book. I loved reading ‘The Hogs of Cold Harbor’. I was in the Civil War on the Southern side. That is no small education for a Northerner like me.”— Norman Mailer

From the Author

By Richard Lee FulghamFormat:Paperback|Amazon Verified PurchaseThe Most Insightful Review Yet – A Serious Addition to American Literature, April 17, 2006

This review applies to: The Hogs of Cold Harbor: The Civil War Saga of Private Johnny Hess, CSA (Kindle Ebook version, Paperback, Hardback)

[…]

This is an exceptional work of emotional catharsis.

Without a doubt, the Civil War has come to represent a deeply divisive aspect in American historical thinking, assuming collective proportions and seemingly symbolizing some sort of moral or ethical bifurcation in the national psyche. Over 600,000 American men died during the Civil War, a quarter of all white Southern men of military age had been killed or maimed and – in the pitiless words of the economist – “the state of Mississippi had to spend twenty percent of its revenue on the purchase of artificial limbs for Confederate veterans.”

Richard, in his transcription of a Confederate private`s war diary, advances with a bucolic attention to detail and a spirit of pastoral scholarship rare in a writer of history. The Hogs of Cold Harbor is a model of exploratory and meticulous investigative procedure. It is vibrant with detail – be it domestic, culinary, sartorial, anatomical, agricultural, botanical, carnal or otherwise. The amount of minutiae, particulars, specifics and ‘trivia’ derived from the conventions of the age, is extraordinary and sometimes totally hilarious. And it all seems to spring naturally from the narrative rather than consisting of contrived or superimposed impedimenta. Indeed, his contemporary account of Russell County`s Hog Killing Day adds a great deal of indigenous, local information to what may have seemed an elapsed folkloristic tradition, even if it is presented in his unrelenting, sometimes stomach-churning vivisection.

There is absolutely no attempt to sanitize indigenous tradition in order to make it more palatable to twenty-first-century sensibilities, and I defy anyone to experience Richard’s indefatigable capacity for painstaking adherence to intense and sometimes gruesome detail without feeling queasy. Nor does he shy away from the South’s political blindness about the Federal Union or its own unthinking endorsement of the sanguine nonsense of ultimate military victory. The reality of it was, in fact, that the Confederacy had only two million men of military age against the North’s seven million, and that is not taking into account the hundreds of thousands of Negroes in the North who might well be allowed to serve. The other advantage the North possessed was the extent of its industrial capacity. Private Johnny Hess makes no attempt to hide his distaste for the disingenuous “holier-than-thou” Unionists, or deprive his age of the testimony he gives of the “Godless Yankees”.

It is acceptable, no doubt, to disagree with the Private, though I fully endorse the gist of Richard’s Fulgham’s own reservation about the North’s excessive self-righteousness. Nor does he allow individual sentiments to obscure historical facts, but simply to illustrate the narrative. The South’s uncomfortable legacy is a part of the general malaise of America`s past, as were government policies against the Native Americans, who were placed on reservations and taught white ways, or the enduring extremes of racial segregation and subsequent international “imperialisation” of the Globe. Nevertheless, this long, bloody and intimately narrated chronicle does what one expects history to accomplish: tell a tale of long ago that throws a prickly and uncomfortable light on an immutable truism of history: That the struggle to survive creates monsters!

Frankly, if the educational authorities ever considered a cure for the fallacy that being Southern means being reactionary they could do a lot worse than go for the honest approach and make this book recommended reading in all American schools.

Richard Fulgham’s homage to the hogs, however, comes in other ways: “The hogs were smart in an all-too-human way…” And there, in an unholy juxtaposition, lies the author’s central challenge: how to convey the inherent swinishness of man? His solution, indeed, is imaginative and ingenious, even if it is exceedingly predatory. But then again, it is incontrovertibly inherent in the nature of the beast – indeed reverting to it. Man-eats-Hog! Hog-eats-Man! It sounds improbable but, trust me, it works. The overlapping destiny of these hordes of swine and men scavenging for victuals on battlefields inundated by the tidal wave of death, are eerily recorded. Given the entirely unreasonable circumstances, “Human warfare was just God’s way of slopping the hogs.”

Private John Henry Hess epitomizes America’s bucolic youth, emphasizing rugged patriotism and pioneering self-reliance. Richard’s touching vignettes about Johnny Hess’ life with his young daughter and her blemished but loving mother suggests the unexplored tenderness of someone who can rewardingly illuminate the beauty of the human face with a redeeming love for its imperfections. The book might have profited had he kept some of its bathos off its pages but, on a much more elevated scale, there are moments of penetrating poetry. The liberating fluidity of the transformation of a “hand-sized, blood-red stain covering the left side of her face” into “a beauty made that much more awesome because it was so terribly flawed,” leaves one with the certainty that the author’s second vocation may well lie in writing about the more redemptive qualities of the human beast.

But this cathartic, educational and scrupulously researched “nonfiction novel” is, nevertheless, the result.

A Subversive Review of The Hogs of Cold Harbor

by L. M. Warren

When I first read the book well over ten years ago, I thought to myself:

I want to write like Richard Fulgham.

I wanted to create literature that was witty, disturbing, and bludgeoning in its moral obligation. At the time, I never even knew authors could write that way; so unhinged and so impassioned they might as well be acting, they might as well be bleeding onto the page.

Now after my second reading of it, my thoughts have evolved into:

I believe every author ought to write like Richard Fulgham, or just shut the bloody hell up.

Too many authors today are given a free pass to write shit just because they know how to construct a sentence and have “feelings” about various issues. But 90% of these books (traditionally published and self-published) are nothing but pig shit. Agenda-oriented and corporate sponsored drivel that is only circulated because it can sell to Democratic or Republican audiences. Audiences that want reassurance, that want “research” they can quote to build their house of cards they call an ideology. The writing doesn’t matter, the message is secondary to the characters—the stock characters who embody the Great American lifestyle. They learn only respect for the government, they change, only to be a better consumer.

The Hogs of Cold Harbor, on the other hand, is a wonderful absurdist Civil War epic that boldly questions the status quo of patriotism and social dogmas. Telling the “obscene” story of how the Confederate States of America saw themselves as the heroes against Lincoln and Grant’s villainous Union (a perspective so alien to the mainstream no agent would probably touch it) the story skewers the plight of humanity, human beings forced to self-define their own “honor” in the midst of moral chaos.

The book isn’t exactly subtle, but rips apart our hopes, dreams and false notions of civilization, exposing us as godless, violent creatures who create masturbatory fantasies of why we are justified murdering our fellow man. Throughout the savage narrative, which sees vivid war imagery and an almost pornographic degree of realistic description of gunfire carnage, we are reminded that among all other animals, human beings are the ones truly without honor.

We hear the story of Johnny Hess, the perfect representation of innocence, as he slowly deteriorates into a cynical onlooker, and then into delirium as he struggles with the concepts of Cold Harbor hogs resembling human beings in their war formations, funeral processions, and of course, the way they stared with those knowing eyes. Hess, at various points in the story, screams his patriotic dogma and his simple mantra that keeps him surviving; “that God-fearing humans have honor and hogs ain’t got none!” But over the course of some 400 pages of Civil War battle summations, he is forced to recant as the bitter end approaches, realizing that although hungry hogs may have simpler minds, they are superior to humans in at least one aspect: they never kill their own kind! We are the ones foolish enough to find reasons to fight, and to create barriers of religious, political and social differences that require violent solutions.

The book reaches its peak of creative brilliance when author Richard Fulgham himself appears in the book (or perhaps a family ancestor?) and explains an uncomfortable truth about the human species: we’re not that much greater than monkeys, if even that, and all we can hope for is that we walk away from conflict unscathed, take a lesson from the hogs, and let the most savage of creatures battle it out to certain death.

Because as the book teaches us, a greater lesson than anything you’ve ever learned in history class, is that the Hogs won the American Civil War. While the northerners and southerners killed themselves over philosophies and vengeance that are long forgotten, the hogs stuffed themselves with human carcasses for those long years, some living, some dead, and had the largest feast of their short-pig tailed lives.

I’m still not clear whether Richard’s insertion of Richard into the story is a literary blasphemy meant to break the fourth wall, OR if the Richard Fulgham I know and I love has always been a fictional character the many years I’ve known him. What a mischievous shadowcast it has been, Richard, or shall I say, Johnny…or maybe ever Porcino or Napoleon…or Pickett, or whoever the HELL you REALLY are, my illusionist friend! You are the master illusionist laughing madly at us all, calling yourself a “monkey” in great pride.

You are a fantastic monkey, my friend, and a wiser monkey I have never known. And there has never been a finer collection of monkey scratch than The Hogs of Cold Harbor, one of the greatest books I ever expect to read in my lifetime. It deserves comparison to anything Hemingway or Twain ever wrote, and perhaps it would have been compared to such if only Richard had dumbed his brilliance down to the simple argument of: “America is great and that’s why we won!” which is all people want to read anymore.

The complexities of truth are an uncomfortable read for sure, which is why most people won’t have the stomach or the heart to finish the whole book. But for those who make it to the end, you will get your money’s worth. A book that beautifully puts into words everything that you’ve ever thought about in your quieter moments about the lure of nationalistic furor—and once fell for the pig shit of Obama’s “Change we can believe in” or Trump’s “Make America great again”—all propaganda that soldiers can see through in a heartbeat, especially when watching their comrades fall apart like bloody Lego pieces right in front of them.

It is a book that I wish I could write, if only I didn’t detest the simplicity of the Traditional Adult Narrative that permeates most books today, which are not worth my time.

I seek refuge in writing comedy, in the ADHD Internet troll voice of the Common Era, as I demonstrated in “The End of the Magical Kingdom”, another war book that hides behind a colorful metaphor.

But what I enjoyed most about Richard’s voice is how he manages to tell a story that’s as true as it is absurd, as dramatically engrossing as it is laugh out loud funny, and as tragic as it is fun. Somehow, the author creates a narrative and true historical chapter that doesn’t seem phony or long-winded, like the typical adult novel sitting in the bookstore.

The fact is most authors today don’t write like Richard Fulgham, and more is the pity, because most book shelves are dominated by the likes of Stephen King, who is a hog shit of an author and an even bigger piece of hog shit as a human being.

I didn’t just love this book, I was immersed in the experience of being surrounded by war. I was there, with Richard, as we took up arms, believing hearsay and being deceived by lying generals. I was there with Richard, as we saw hogs devouring wounded soldiers, speechless and with streaming tears in our eyes. And yes, I was there with Richard as we visited painted whores and drank liquor to numb the pain.

In a time in America where political dogma is rising again destined to meet to a furious end, The Hogs of Cold Harbor is an injection shot of sanity. Now if you’ll excuse me, I must go tend to my piglets and gardening, shoving away mad trauma of talking heads and human gore, living as peacefully ever after as we can manage.