By Karla Fetrow

Catch the golden ring and win a free ride. The merry go round horse lifts lightly, airily off the ground and settles again a yard inside the circle and a mile into imagination. The rings roll down from a metal arm, one dull silver one after another, to be plopped within a canopy. I ride Lightening. I ride the beautiful black pony with the sapphire studded saddle and ahead, the golden ring glistens. I’ve practiced this moment a long time and catch it easily. Another ride, another moment in another land, faraway and secret, with Lightening.

I show the ride conductor my prize. “Good job,” he tells me, patting my the head and taking the ring. “But why don’t you wait a little while? We’ve got a lot of customers right now. Come back when the line looks empty.”

I nod. It was one of the drawbacks of being a carny brat. There were lots of free rides, but only when the line wasn’t busy. I wandered around, hoping to find a neglected ride. The roller coaster was nearly always busy, so when the grounds were full, as they were today, there wasn’t much chance of adding it to my amusement rounds. The airplanes, attached by cables to a pole, were idle, but it was the baby ride. The steering columns in the cockpits wouldn’t tilt the wings right or left as they did on the more grown up ones, nor could you push a peddle to make your plane take dips and reach enormous heights. It just went around in a boring circle while toddlers peaked anxiously out the plastic windows.

I sighed, filled with an odd sense of loneliness among all these happy people dashing around in couples and groups. On the slow days, the carnival was fun. On the slow days, my mother drove through the neighborhood, rounded up a few our neighbor’s kids, and took us all out to the carnival to make it look busy. Those were the best days. Those were the days when everyone had time for us; the ride conductors, the concession sellers, the jugglers and clowns. We were allowed more liberties than, more secret treats, more behind the scenes treatment. On days like this, no friends were allowed free entrance and everyone who was inside was busy. Even my older brother and sister pitched in to help out.

“You can’t find anything to do?” I looked up at Ko Ko the Clown, who I knew to really be Dick Rand, and shook my head. “I caught the golden ring, but I have to wait.”

“That’s good. That means a paying customer didn’t get it.” He laughed and I pondered at his humor, but he was the boss. “Look, the train is empty. Why don’t you go sit down in it and wait for it to fill up?”

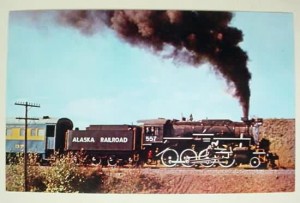

That I could do. I liked the train. It was an exact miniature of Alaska Railroad’s most famous train, “the Moose Gooser”, complete with smoke stack and wide grid in front, painted Alaskan blue. I climbed into the last car, my favorite, holding my breath as the sight of one child waiting to take a ride caused others to want to try it out as well.

It was a strange time, I suppose, but pioneer lives always do bring with them a bit of strangeness. We were building a town, this handful of people carving out the wilderness, and through some great majestic favor granted by the gods of industry, it occurred to someone, one day, that Alaska needed a carnival. The only problem was that the someone who somehow made it up here with a half a dozen carny rides and some concession booths, went broke within a few weeks of his opening and was desperate to sell. By even more astonishing good fortune, Dick Rand, a civil service co-worker with my father, decided the carnival would be a great investment. It didn’t take a lot of hard talk to convince my dad, his pal and buddy, who had a strong taste for the stage, thus all things fantastic, to co-invest with him.

Those first years, when Anchorage was as much a pioneer town as the rest of Alaska, were not easy for the newly vested carny owners. In the summer, the only real money that was made was during the holidays; Memorial Day, the Fourth of July, the weekend of the State Fair, or sometimes during a spectacular summer day when the sun shone brightly through our usual fog cover and it felt like Hawaii had come to visit. The entire venture probably would have thrown us as miserably into debt as the original owners except Dick Rand came up with another idea.

Television technology was finally coming to Alaska with the triumphant erection of its first studio and tower. Although its beginning was embedded in no more than a half a dozen network shows, as quickly as the station went up, the local stores were emptied of their televisions. Dick Rand’s idea was to run his own one hour long television show, padding it with cartoons and taped in episodes of the Mickey Mouse show, with my dad as his side-kick.

The name of the show was “Kartoon Karnival” starring Ko Ko the Kenai clown and Chu Chu the Chugiak clown. For a clown, Ko Ko was very curiously the straight man. Each week, the show sponsored half a dozen children as guests. Ko Ko interviewed the kids; asking them their names and a little about their lives; the kind of questions you usually ask kids; what do you want to be when you grow up, who’s your favorite movie star. My dad, as Chu Chu, was the funny man. He pulled coins from behind the ears of the kids, had a water squirting flower, and looked around in astonishment whenever he “mistakenly” sat down on a horn that sounded suspiciously like a very loud fart.

The show brought in a bit of extra revenue, but mostly it gave us ample advertising space for the carnival. Sometimes, they ran out of kids to host and a phone call to my mother would quickly round up the gang and whatever neighbor kids had been lurking around the house, hoping something like this would happen. I wasn’t one of the best candidates for the show. Mainly my eyes remained fixed on the gigantic cameras and fascinated by the sight of me staring back on the screen. My answers to questions were usually a series of convoluted giggles. It was at that terribly early age of six or seven that I began to understand I had stage fright and would never make it as a movie star. I don’t think this inability to show off in front of crowds was on my father’s planning board. After all, he had successfully taught us to speak from the diaphragm and never turn our backs on our audience; even when we were throwing tantrums; but somehow, he would just have to work around quiet Karlsie.

He found his child aide when my sister, Mary, grew some legs that she could actually walk around with instead of chubby, waddling stumps topped by an oversized belly. Mary, who watched the trapeze artists and acrobats with awe, was soon turning cartwheels, hand stands and back flips with ease. My dad had my mother make her an identical clown costume, put on her make-up and wig, and called her Chu Chu Junior. A starlet had been born.

Sometimes, the carnival meant traveling. When it did, we were usually carried to a campground, where we amused ourselves by catching minnows while pretending to fish, exploring anything that looked dangerous and wheedling any nearby neighbors who had horses into letting us ride them. Sometimes, the travel agreement included a cabin we could stay at while the carnival did its circuit. One of these agreements took place on the Kenai Peninsula. The Rands and our family shared two very charming cottages, with a single electric line and two naked bulbs, a communal hand drawn water pump outdoors and a ranch full of penned up horses outside. No more than a few hundred yards from us, the ocean pounded and thudded against a sandy beach.

We were in paradise and didn’t care if we ever left. We learned very quickly though to be careful what you wish for. The carnival was only to last three days. The first two days were sunny. The third day it rained. It began lightly enough, but the drops grew larger, more persistent. When the carny crew returned to camp that night, they were soaked and miserable. We all sat up drinking cocoa , drawing shadow figures on the wall by the flickering light bulb and telling stories until everyone was warm, relaxed and dry again.

The rain continued through the night and on into the morning. The electric power died and Dick Rand brought out a battery operated short wave radio to catch the news. The road was flooded. We would not be able to leave until the rain stopped. The next two days, we entertained ourselves as all children successfully do regardless of the weather, while the adults grimly went around trying to demonstrate some sort of illusion that they were busy, but it was never clear with what except for keeping the radio tuned. It wouldn’t have been so bad but we ran out of food. Only enough had been prepared for a three day trip and we had been pretty generous in accessing it during the stay. Now, there was nothing left except four gigantic bags of carnival popcorn and a couple of cases of soda. It would have to suffice. It did. The sky finally cleared enough on the third day for us to move out, but one thing we all mutually learned from the experience; you absolutely can survive on popcorn for two days. It’s the best emergency food supply there is.

I suppose, if you wanted to take the modern kill joy perspective of child labor laws, Dick Rand and my father were guilty of exploiting their children, and yet I can’t imagine any form of child exploitation my siblings and I would more willingly fall into. My father was a curious character; extremely formal, serious about his civil service duties, and passionate about his social role. His face was usually stern and able to intimidate stout hearted adults, let alone children. My mother used to say my father loved playing a clown because it was the one time the children were not afraid of him. He played it well, making them completely forget his usual authoritative figure as he played silly magic tricks, fumbled his juggling, fell off stools and tried to keep up with Chu Chu Junior.

With Dick Rand, on the other hand, it wasn’t so much a hankering to bring his acting skills to the surface as it was that he basically saw through the eyes of a child. He instinctively knew what they thought, what they wanted. Because of this, he was amazingly tolerant. Left in his station wagon one day with a back end filled with cases of soda, while he and my father were negotiating a contract, my siblings and I, along with his daughter, Renae, became restless. I’m not sure who started it, either Renae or my brother Larry, who was closest to her in age, but it occurred to one of them to shake up a can of soda and squirt it at the other. This led, of course, to one minor transgression after another, until it became an all out war. By the time our parents had returned, nearly an entire case of soda had been opened and the inside of the vehicle looked like the rain forest had invaded it. Everything dripped with fat, sticky beads of colorful soda pop.

If it had been my dad’s car, it would have meant six months of condemnation and such hell like activities as studying all the countries in Africa, washing, waxing and polishing the car and keeping our rooms clean on a daily basis. Dick only looked inside with utter amazement a few seconds, scratched his head, then laughed. He only laughed. Then he apologized for taking so long, and ended by saying, “but we got the contract! Let’s have a picnic and celebrate.” We stayed in the rather sticky car until we’d driven out to the edge of the inlet where the wild flowers grow and small creeks murmur and had a glorious day.

Renae was probably the first woman I ever fell in love with. Not that she was a woman at the time I first met her, but she was eight years older, so when I was eight, she was sixteen and quickly learning all there was to know about womanly crafts and guile.

She had ginger colored hair that she set off with bright looped earrings. Sheaths of sparkling bracelets covered both arms. She carried a tray that was supported by a leather strap that dangled from her neck. The tray was covered with cheap jewelry and carnival trinkets. Whenever she caught someone’s interest, she unfolded the spindly snap-out legs under the tray and began her spiel. She indulged my interest in her, allowing me to tag along and paw through the items that my father said were too gawdy and cheaply made to wear or own. She told me when I was old enough, I could have my own tray. This made me very happy. She was the only one who saw any potential in me as a carny worker; until Danny Caulfield came along.

Unlike Dick Rand and my dad, who shed their clown costumes with the last tinkling sounds of circus music, Danny seemed to be made for the carnival. He always wore bright, clashing colors; feathered caps and intricately tooled cowboy boots. He always kept strange pets; snakes, lizards, performing rats, even an armadillo. There was always a group of beautiful people; acrobats, tight rope walkers, exotic dancers, close by his side. Wherever he went, heads turned, people followed, curious as to what exhibition he would perform next. Ko Ko and Chu Chu played for the kids. Danny played for the crowds.

Danny and his entourage were a successful addition to the carnival. So successful, that soon Danny was buying shares, and in very rapid time, became a full partner. When he first arrived, he began paying a lot of attention to Renae. She was nineteen by then, smoke and drank. I couldn’t join her in the tent where she sat with her shoes have kicked off in the cool circumference of a beer cooler. I watched while she talked and laughed with Danny.

I thought he was her boyfriend. I wondered how it must be to be Danny’s favored girl, how it must feel to tuck your arm in his in front of the dazzled admirers. I asked her about it and she laughed. “He’s not my boyfriend. I like being with Danny, but it’s just for fun. We’re friends.” She leaned closer and whispered, “it’s not really girls that he likes.”

I was too young to understand this. I “liked” without boundaries, boys and girls, young people, old people, whoever it was enjoyable to be with in my child world. My child world was changing rapidly however, and Danny Caulfield’s preferences came up more than once over the next couple of years, each time stirring up some sort of fervent, defensive indignation in my parents. They didn’t like it when people talked about Danny. They liked it less when neighbors called to gossip about him. Even more disturbing was when the television station refused to allow Danny on the set. “I don’t care what he is,” my father said. “I see a man. I see a hard worker. I see a smart man who knows how to run a carnival.”

Whatever his preferences, Danny was still always surrounded by girls. They didn’t compliment him; he complimented them. Despite the sequined costumes, their piled hair and their high heels, the girls were all somehow more beautiful, more glamorous, when they were with Danny. Danny, all by himself, was a magnet.

Although I followed Renae around like a puppy, Danny didn’t notice me until my fourteenth year. He might not have noticed me then, except I became fascinated by one of the snakes he carried around his shoulders. I asked if I could pet it, and he let it slip from his arms to mine. “You’re not afraid of it?” He asked. I shook my head. “Then maybe you could become a snake charmer,” he suggested.

I thought this was a wonderful idea and ran off to tell my father about my new ambition. He wasn’t pleased. “You are not going to wear a skimpy costume and gyrate in front of a lot of strange people with snakes around your belly,” he told me. “If you want to work in the carnival, I’ll get you a job in the cotton candy concession.”

That was better than nothing and it meant I’d get to make some money. I spent two weeks spinning cotton candy until I began to feel like I’d turned into a confection. There was one good thing about it. I met lots of boys who hung around all hours asking questions in between the very serious business of dispensing colored sugar. The only problem was, most of these boys were in the military. To make matters worse, my oldest sister was also working a concession stand and finding similar company. Suddenly, with very little announcement and fewer explanations other than a vast disapproval of high school girls dating military men, our carny days were over.

It was time to move on. My father sold his share of the business to Danny. Kartoon Karnival had folded a couple of years prior. Another television station had come to town, and there were rumors of a third one. Ko Ko the Kenai Clown and Chu Chu the Chugiak Clown gave way to Scooby Doo and American Bandstand. We were forced to surrender our ambitions to become exotic dancers for the more common place ones of trying out for the basketball varsity team, joining band or sitting in student council. They seemed pale in comparison, but we adjusted.

None of us ever went back to working for the carnival, even though every summer there were positions open for ride operators and concession stands. As children, we had been fond of it, but we were as accutely conscious of the illusions of the carnival as we were of the differences between real life drama and our make believe creations. We knew which games were rigged and how it was done. We knew about shills and hawkers. We saw the strings and mirrors that were used to manufacture magic. In some ways, it spoiled the painstaking care to introduce a world of strange beings, of wild dreams, of reckless gambles and the few fabulous lucky, but at the same time, I think we were enriched and privileged to know the people behind the scenes.

That’s just not fair, Karlsie. You’re going to win the Subversify “Carnie” contest and you’re the one throwing it!

Great job. Very nostalgic and moving piece of work. I can see a lot of heartbreak amid all the laughter. Changing times, all you can do is laugh. Your father sounds like a wonderful fellow. Ah, for the old days when ko kos and chu chus were the real entertainment.

No box of chocolates for me, Mitch. I promised Grainne i’d write my own carny experience but it wasn’t for the contest. I was actually pretty hesitant about beginning a story from a young child’s point of view, and almost nixed it. However, when i did a search just to see what the engines had archived concerning some of the most prominent characters in Alaska’s pre-pipeline days, i found absolutely nothing. Not one word about Dick Rand, Alaska’s first carnival, or even a coverage of the first radio station. It seemed so unfair; the people who gave all are forgotten and silenced by the people who hog all the limelight and glory.

I suppose it does make me feel a little sad. Alaska changed almost overnight with the heralding cry of oil and riches. The defamation of character continues as “progress” takes wide swipes into rural communities, pushing aside the local people to create an illusion of modernization and prosperity. They mow down the trees, flatten the hillsides and ruin the sleepy, pastoral settings with flamboyant homes, strip malls and parking lots. We weren’t even given time to grab our asses and say goodbye before our life styles were shoved out the door. It was a kinder time, a less selfish time, a time when people worked together. Although it’s hardly a popular subject within our self-absorbed, fast-paced society, hanging onto the next catastrophe like the dramatic scenes in a soap opera, i think i will continue to construct the early days of Alaska’s history. And thank you, Mitch, for continuing to be such an avid, loyal and gentle reader. It means much to me, especially knowing exactly how well you can write and how deeply you can carry a person into your perspective.

Karla my heart is warmed to the core. Not only is this a lovely memoir, but I am so very glad you did start the story at the beginning.

We tend to forget so very much so very fast in this era. The child labor such as it was is what went into making adults with a desire to work, even a love sometimes. We protect our children to much, probably to dire consequences later.

And, Dick Rand as well as your father deserve to have their story remembered. It is the people like them that make communities and ultimately our world a magickal place.

Grainne, your point about child labor is a very good one. It caused me to sit back and reflect for awhile. I’ve noticed among small, private businesses that the children, who are often around, can’t wait to do something to help out with the family enterprise. Young girls learn how to operate a cash register before they are twelve, although they officially are not allowed behind the counter, young boys jump to carry their dad his mechanic tools or pick up their first chain saw while it’s still nearly as big as they are. I don’t see that it harms them. They develop strong work ethics before they are out of high school and already comprehend how many hours of labor it takes to buy that new X-box or a second hand vehicle of their own. They don’t expect to have things simply handed to them. They expect to earn them. They are far more prepared for the work world than the children who had everything handed to them until they were eighteen, than told by their parents, “okay buddy, you’re on your own now.” What really seems peculiar to me is that the average child carries home so many academic studies by the fourth grade, s/he is lucky to have one hour of play time, yet adult society seems squeamish about letting an eleven year old child learn the rudimentary fundamentals of labor.

For me, writing about that simpler past is like sitting under a cool breeze on a hot summer day. It’s an escape from the clamor and aggression of modern society, but it’s also like opening a door to the way things could be. We don’t have to shed our characters, our performers and clowns to fit the beat of quickening tempo. We don’t have to brutalize our neighbors. We can be gentle and kind. For some who were raised in early Alaska, their clearest memories are of hardship and poverty, but mine weren’t. I remember a people; a wonderful, thriving people; living bravely under the shadow of nuclear missiles yet believing in the future. The prospect of war was as great then as it is now, yet they put aside their worries for awhile, went out to visit the carnival or other places where entertainment was cheap and laughter was free.

Glad i discovered this web site.Added “Life with a Clown” to my bookmark!

I’ve just subscribed to your RSS feed. I love your content.