I sat at the table in the little cafe, watching the rain dance on the pavement outside, beading the window and turning the tall grey buildings misty and indefinite. The clouds were so low overhead and so grey that the buildings vanished into them, and the effect was as though it was raining inside an immense grey hall. It made me glad to be indoors. I do not enjoy this weather.

I noticed the man at once, walking hunched over under an umbrella towards the cafe. He was the only pedestrian I’d seen yet after I’d left my vehicle and trotted to the cafe through the rain.

I watched him all the way, until he passed my window and went round towards the door. I sipped my drink, taking a quick look at him as he entered. By the time he had folded his umbrella and put it in the stand, I’d turned back to the window, and watching him in the reflection on the pane.

He was probably not past forty-five, but he looked much older. There was a tired look about him which I sensed right across the cafe, and his shoulders were stooping. I watched him in the window as he looked at me, glanced away, and walked to the centre of the cafe, looking around. There were no other customers, and in the end he finally turned back to me. I sipped my drink as I watched him come up, in reflection, until he was standing on the other side of my table. Then I put down the glass and looked up at him in polite enquiry. “Yes?”

He cleared his throat and started to back away. “I’m sorry,” he said. “I must have got the wrong person…”

“Probably not,” I told him. “You’re Mr…” I already knew his name, of course, but he needed to say it.

“Kangas,” he told me. “Henri Kangas.”

“Yes.” I indicated the chair opposite. “Why don’t you sit down, Mr Kangas?”

“You’re the one who’s supposed to meet me?” He sounded incredulous. His deep-sunken eyes were scanning the cafe, as if hoping to see someone else who might be more like his idea of a spacer. But there was only me.

“Yes,” I repeated. “I’m Jamileh Rezazadeh.” He blinked at the name. I tried to see myself through his eyes: dark, square-jawed, with thick eyebrows and my big Iranian nose, my hair covered by the headscarf I never normally wore. Some perverted impulse had made me tie it over my hair today. “I’ve been expecting you,” I said.

“So,” he said, and sat down. His hands were big and hairy, and he began twisting them together on the table. “I’m not sure I want to do this.”

“Nobody ever does, not completely,” I said. “But it’s your decision to make.”

“Tell me again,” he muttered, looking at me in flashes, glancing at my face and away again, quickly. “First, tell me if you’re an agent for the ship people. I thought I was to deal with them directly.”

“No,” I assured him, “I’m not an agent. In this business we don’t use agents. I’m a ship person, Mr Kangas; to be more precise, I am the ship person, a fully qualified pilot.”

“Then…” He didn’t follow up on what he was about to say, but I knew what he was thinking: that even though I looked about thirty, I was old, probably much older than he was; and he was right. “You’ll be piloting the ship we’ll be leaving on? If,” he added hastily, “we agree to leave on it, of course.”

I didn’t answer him directly. “Dawn,” I said. “That’s what we call it, Dawn, though the official name’s something else. We call it Dawn because we think it’s a new dawn for the human race. Do you know what Dawn is like, Mr Kangas? You probably have seen pictures and holograms, but you don’t know what it’s like. Unless you’ve been there, you can’t.”

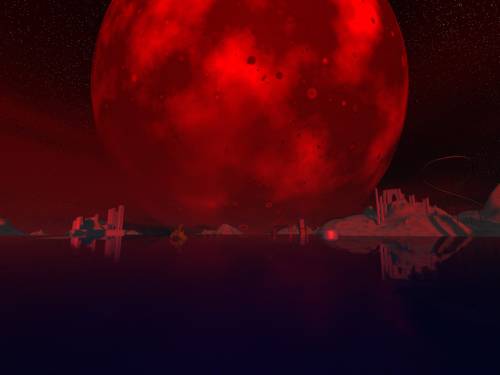

I let the memories wash over me as I began to speak. “You should see the sun come up on Dawn. It’s a red sun, huge and cooler than ours, but it’s got billions of years to go before it burns out. And on Dawn, when it rises, it washes the sky with pinks and reds and oranges, like you can’t imagine.

“I was once in a forest on Dawn at daybreak.” I remembered the cool, drifting mist, the thick rubbery vegetation, the bracing air. “I wasn’t lost, but I was pretending to be.” It hadn’t been hard, not then, because there was only the one town on Dawn, right next to Port Cosmos, not counting the satellite scientific stations. “I saw the sun come up from the top of a hill.” I tried to put in words what it had been like, the roseate glow that suffused the atmosphere, and turned each drifting particle of mist into a tiny ruby. “And that’s when I fell in love with the place.

“And then the nights.” I told him of the sky of Dawn at night, ablaze with stars, a hundred times more than earth’s deserted skies. Dawn was closer to the centre of the spiral arm of the galaxy, and the stars in its sky shone in swathes of red and blue and yellow. I told him of the rain of Dawn, falling straight down from the upper reaches of atmosphere in a crashing torrent that seemed to beat the breath out of your body and yet left you feeling cleansed and alive.

“Dawn is a wonderful planet, Mr Kangas,” I said. “Earth-sized, with a breathable atmosphere, no dangerous predators and no lethal diseases, but then you know all that anyway. What you don’t know is what it means.” I waved a hand at the window. “Outside, there, this world’s dying. Whatever anyone pretends, everyone knows that it’s dying.” We both watched the polluted rain fall down past the concrete canyons of buildings for a minute. “All we have here,” I reminded him, “is economic collapse, environmental holocausts, and wars over resources. It can’t go on like this forever, you know. And on the other hand, we have Dawn.”

He looked down at his hairy twisting hands. “From what I found out,” he said, “this immigration isn’t actually legal.”

“It isn’t,” I said frankly. “But the laws are strictly for the books. My ship is a regular cargo liner, as you know; we go out on a multi-stop trip, mostly to barren little planetoids and mining stations. The only really important stop is on Dawn. We have accommodation that’s never used, an entire bank of stasis units, twenty of them, and –“

“You mean the coffins,” he said, with the slight shudder I’d come to expect from those who had never used one.

“They’re stasis units,” I said firmly. “Not coffins. They’ll keep you in suspended animation for the trip. Even though we’ll be going at nearly the speed of light, in ship time, a couple of years and more are going to pass. Yet you won’t get older by more than a day or two.”

“And can you tell me one more thing?” he asked. “Why me? It’s not as though I’ve got any special skills to contribute. Nor can I pay enough to make it worthwhile for you.”

“It’s not a matter of pay, sir. Nobody can pay enough to make it economically viable. But some things are beyond economics.” I wasn’t about to tell him that we’d take anyone of productive age who was willing to go and wasn’t so significant as to be missed. We needed people on Dawn. “You do realise that once you go, there’s no return? It’s a one-way ticket, strictly.”

“I know,” he said, staring down at his hands. “That, I know.”