There are few people who avidly watched movies in the 1980’s who are unfamiliar with the film, “Salvador”. Presented as a fictional story about a young reporter whose drinking habits killed his job opportunities, the movie carries you into the brutal civil war that characterized 1980’s El Salvador. Believing he could earn some bucks as a free-lance writer, but doing an exclusive coverage of the revolutionary forces, Richard Boyle (James Woods) almost immediately begins witnessing some of the worst horrors imaginable in human aggression. The tempo quickens after the archbishop is assassinated in public while performing mass, and four peace-keeping American nuns and one lay woman are raped and murdered.

Only the main characters were fictional, however. The historical background was viciously accurate. I was living in Mexico City at the time of these terrible deaths and watched the whole country go into mourning. You would have thought this message of violence would have kept peace keepers away, but it wasn’t so. It instigated two distinct forces. One was among young Mexican citizens, already on the verge of creating their own revolution, preparing to fight and die by opposing the Salvadorean military regime. The other was an International coalition of human rights activists who were preparing to give aid and die for the oppressed El Salvadorean citizens.

I met one of these young peace keepers while standing on the corner of a Mexico City street, selling handcrafts to tourists. Mexico was seeped deeply in the peso crash, and I had lost my job as translator for a Mexican/ American business firm, but like the free lance writer in the movie, Salvador, I sensed a story. I had stayed, taking my chances with a Mexican street artist who had become my partner.

Vicky was small, pretty and positively exuded earnestness from every skin pore. After buying a couple of bracelets, using some of the simplest Spanish terms to close her purchases, she tried speaking to me in somewhat barbarized Spanish. “I speak English,” I informed her.

Breathing a sigh of relief, she told me she was from Canada and was trying to find passage into El Salvador. “Why do you want to do that?” I asked. “They’re killing each other there.”

“Well, that is why. I am a Quaker. I was supposed to meet here with a group who were going to El Salvador as mediators, but I arrived too late. They’re already gone, but I still want to try and help.”

I stared into her eyes. They were beautiful, gray and calm. I would have chalked her up for a fruitcake if I had been able to ignore their gentle, penetrating clarity. “Let me ask my companero. We might be able to help.”

Jose was somewhat reluctant to assist this gentle girl. We had discussed going to El Salvador ourselves, but the general contention had been that I would not last more than two weeks in the war torn country. It had been enough to put my noble thoughts on idle. But here was someone softer, gentler, more innocent than myself, perfectly willing to put her life on the line for her ideals. The experience was humbling.

We took her to a small town in Oaxaca and left her in the hands of some revolutionaries who were skilled in border crossings. Their general function was in smuggling people out, but sometimes they smuggled new recruits in.

It’s a little odd to think now that my first real contact with those relying on faith was with a young Quaker from Canada, but as the years progressed and the peso continued its downward spiral, I began absorbing the enormous faith of the Mexican community. I began seeing it in small things.

We could no longer afford the high cost of living in Mexico City and switched our home base to a small Indian village forty miles away, coming into the city only for supplies and weekend stints at the enormous open air, Lagunilla Market. On the weekends that we weren’t in the city, I’d watch from the window of my small hut as a little monk labored his way up the hill each Sunday to perform mass for the villagers. The chapel wasn’t much larger than the hut and had room only for the alter and six benches. The villagers were so poor, there were never more than a few coins left in the coffers set out for offerings. The only reason he made this weekly pilgrimage up a very tall hill on a high plateau, sweltering with desert heat in the summer and bone chilling conditions in the winter, was because the villagers had pleaded with him to give guidance and direction to the congregation.

Each Sunday, he arrived without fail, and each Sunday the entire village turned out to await his benedictions. The old ones and the pregnant women crowded into the pews. The rest of the populace spilled out from the doorway and crowded together on the turf just outside the chapel. After mass, he would listen to the complaints of the citizenry, soothing quarrels, absolve their humble sins, and even serve as a medical advisor for various ailments. Although he was sometimes offered a chicken for his services, the treasured mole, which was a delicious sauce the town was famous for, or a plate of empanadas, it was but a pittance for the time and patience he took in being with his parish.

Each Sunday, he arrived without fail, and each Sunday the entire village turned out to await his benedictions. The old ones and the pregnant women crowded into the pews. The rest of the populace spilled out from the doorway and crowded together on the turf just outside the chapel. After mass, he would listen to the complaints of the citizenry, soothing quarrels, absolve their humble sins, and even serve as a medical advisor for various ailments. Although he was sometimes offered a chicken for his services, the treasured mole, which was a delicious sauce the town was famous for, or a plate of empanadas, it was but a pittance for the time and patience he took in being with his parish.

One weekend, with plenty of supplies, but no funds, we decided to try our luck at the local market, selling our handcrafts. The town had not seen a full display from us before and was quite enthusiastic about buying our hand-wired earrings and assorted baubles. At the next street stand, a lady was selling bouquets of beautiful, miniature white roses. Feeling resplendent in our new found wealth, I bought a few.

They seemed too beautiful for decorating our hut, however, and on the way home, my mind kept wandering to the strange little monk who returned to our village each Sunday to guide his flock. I felt tender to him, and toward the villagers that had opened their hearts and homes to us. I decided it would be a beautiful gesture to leave the bouquet at the chapel for all to enjoy. I told Jose I wanted to attend the chapel a few minutes before going settling down for the evening. He nodded with understanding.

The chapel was just a short walk from our home. I wondered what I would say to this invisible creator who had somehow kept us safe, who had not only granted us shelter and food, but had even provided us with extra funds for entertainment and a few nice things at a time when everyone was living hand to mouth. I would thank Him, certainly, but I would also ask for something.

Jose and I had been together for several years, yet we had no children. We had agreed the situation was far too serious to bring a child up in, but still I craved a baby of my own. My biological clock was ticking away and it became harder, more painful each year, to see other children playing and running to their mothers’ arms, while I had none to hold. I had made up my mind to ask for a child.

Feeling just a little guilty about this petition that did not include my companion’s blessing, I entered the chapel to pray, but stopped in amazement at the entrance. The pulpit, the alter, the walls, were all decorated with white roses. I no longer felt generous, but incredibly humble. I knelt at the alter, rendered my thankfulness, and delivered my secretive petition.

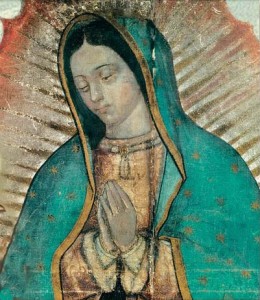

Call it coincidence. Call it what you will, but nine months later, my son was born. I learned soon after that day of flowers, it was a yearly event; an honoring of the Mexican saint, the Virgin Guadalupe. Because I had, until that day, avoided any overt religious occasions, I had not known. It didn’t inspire me to suddenly start attending church, but I did begin to dwell more and more on the power of faith.

Leon was a beautiful, happy, healthy baby, much loved everywhere we went. Our ability as sales people increased as people were attracted like magnets to the cheerful toddler. Jose, who had been surprisingly receptive of the idea of a new family addition, began calling him our lucky charm. Then, the unthinkable happened. Mexico City was hit by an eight point magnitude earthquake.

The damage was devastating. Thousands of people died in the collapse of the centralized buildings. Thousands more were listed missing. We were among the lucky ones. We were on our way to the city to buy more supplies when the earthquake occurred, and did not have to go through its intensity, but we arrived to a crippled metropolis. Unable to raise money quickly enough to immediately leave again, we were stranded.

We suffered with the other street artists. Many had lost homes, family members and relatives. A hotel kindly put us all on the third floor where we could share expenses, food and support for each other during this new crisis. Already stumbling under a financial burden, Mexico was now suffering a physical loss. After trying to retrieve all the victims of the disaster they could, the bulldozers came out and the uncounted deaths were buried under the rubble.

A few days after our arrival, our son grew ill. His appetite vanished, he grew listless and his breathing became labored. We rushed him to a clinic, but the clinic was full, as were all the hospitals. A doctor gave us medication for him and explained that the air quality had grown so bad, all the children under three years of age had contracted bronchitis. We would have to doctor our child by ourselves.

For five days, we kept him under constant watch, barely taking more than an hour or two of sleep at a time. He grew thin and pale, rarely opened his eyes, never cried out and drank soup only as we coaxed it down him. By the fifth night, I was in a frenzy. Our baby was dying. I scrubbed down the little hotel room, even the ceiling, all the time praying beseeching a miracle. There had been miracles, I knew. Nearly a week after the earthquake, while evacuating a collapsed hospital, they had found twenty newborn babies in incubators, still alive, hungry and crying. They were called the miracle babies. I wanted a miracle, too.

I was in too much of a fever to sleep at all that night, but dozed off in a chair next to Leon’s bed. Whether for a few minutes or a couple of hours, I don’t know, but I was startled awake by a small, weak voice calling my name. I opened my eyes and turned my head. My son’s eyes were open and he was telling me he was hungry.

It was the most joyful moment of my life. He willingly ate two bowls of soup that morning, and by afternoon, wanted more. His recovery was rapid. Within a few days, he was sitting up in bed, playing with toys and greeting the street artists who came to the door with their best wishes. In his baby lisp, he told me a beautiful woman had come to visit him while he was ill. As hallucinations are common during serious brushes with death, I thought very little of it until I took him for his first walk in the streets.

Because he was too weak to walk very far, I carried him in my arms. He was happy to be out and about again, delighting when various street vendors gave him small treats or offered a toy from their stands. However, as we passed a store window, he suddenly ordered me to stop. “Aqui!” He cried out. “Aqui es ella. La mujer tan bella.”. Here. Here she is. The woman so beautiful. I looked at where he pointed excitedly. In the window was a statue of the Virgin Guadalupe.

Tragedy was not done with us right away. Two years and one more baby later, we were involved in a car accident that took the life of my companion and one other passenger. With a near fatal blow to my head, I dreamed I was flying through the air with Jose and the young woman who had been with us, when we arrived at a gigantic fortress. Jose and the young girl were allowed to pass through, but I was ordered to “return and take care of the children”. When I awoke, I knew instinctively that Jose and Leticia had died, but my children were waiting for my care.

Leon suffered facial damages so severe, he could no longer open his mouth after resetting the bones to his chin and his jaw. There was no choice left but to return to the United States and the hands of a specialist who could repair the paralysis. The operation was successful and he remains to this day, a very gregarious young man with a gift for gab.

Those years of intense faith and direct communion with a personal God seem to have faded, even though I can never deny the miracles or coincidences I had witnessed, whatever your interpretation of my story might be. I often contemplate the differences between the faith I saw and experienced in Mexico and what we accept as faith in the United States.

One peculiarity stands out for me. There were no true non-believers in Mexico. They all accepted a living God, whether they were saints, sinners, thieves, murderers or simple, honest folk going on with their daily lives. God wasn’t a convenience figure to pray to in times of trouble, an icon to drum up sentiments of loyalty and preservation of an image. He simply was; giving when He thought fit to give, removing gifts for His own mysterious reasons, a manifestation with no explanations for its presence. They didn’t disbelieve simply because of hard times, toil, loss or bitter experiences. The toil, the loss, the bitterness were natural occurrences. The miracle was delivery.

We live in a country that has had far more to be thankful for than Mexico, that has suffered less, that has been given more, and yet we have so little true faith. We take our blessings for granted and curse when our blessings have been removed. We rely entirely on the influence of wealth, the strength of our armies, the magic of our pharmaceutical drugs, but rarely on simple faith. We have become a great nation, but we are teetering. We are collapsing, because we’ve put aside the bonds of our humanity, demanded power instead of tolerance and understanding, and closed our minds to possibilities beyond our own experiences. We insist we know the truth without exploring alternatives. We state we believe while still in doubt. We have lost our way, but will not change our direction. Discord, disagreement, lack of compromise plague us because we have no faith; not in a creator, not in ourselves and not in each other. Toil, loss and bitterness will be the fruits of our downfall. Our miracle will be survival.

La Virgin De Guadalupe is my favorite “saint” and the most interesting to me. Looking at the mythology, she is not a Catholic construct at all. European Catholics will often attribute the “divine mother’s” aspect to her but it seems she is really something older. She appeared, not to clergymen, not to Europeans but rather to HER people. To advise them how to get along and move forward in a time when tensions were high. This is something I can connect to. Not that I am in the least bit Catholic or have an affinity for “saints” but rather the message here and the fact that she was a woman, regardless of whether you believe her a goddess (as some do) or a saint. Women, powerful and humble ones really do make differences that war-like behavior very often cannot.

The matter of faith, it is so personal. When you have it, it’s virtually unshakable and yet, as we see here recently it too can be manipulated. Particularly when one allows someone else to tell them how their faith should function. This is the biggest danger I think in the faithful…the intermediaries.

Which is why I love the story you also told about the Quaker woman.Quakers who not only believe in peaceably service but in receiving personal instruction from their diety. If one is to believe in something, to me this is the only way to believe.

BTW, the Quakers are always active in helping and alieviating suffering. I recommend taking a look at their One Minute For Peace campaign. @ http://www.oneminuteforpeace.org. And no,I’m not a Quaker, but if I were to contribute to something religious, it would be this type of work.

Regarding the statement of there being “no true non-believers in Mexico” – the simple fact of the matter is that, on the whole, regions with impoverished, uneducated people tend to be more religious than people from wealthier, more educated regions: the more desperate the situations people find themselves in (in the case of people in the former Third World, their entire lives are one, large desperate struggle for survival), the more likely they are to believe in the supernatural – if for no other reason than to assure themselves that there is something out there looking out for them (even if there really isn’t the thought provides them with some comfort) and to help them make sense of situations that are beyond their ability to comprehend (due to the fact that they don’t have more than a basic knowledge of their world).

All in all, the kind of faith you describe is a coping mechanism for people who otherwise have little hope in their lives – while it does provide them with a sense of purpose and comfort, it keeps them from seriously questioning the realities that surround them and rising up to assert their own sovereignty as individual beings (as they basically see themselves as being at the mercy of outside forces): getting rid of this sense of dependency is a crucial element in triggering a genuine cultural revolution…

Azazel, to consider Mexico an uneducated country is a mistake. They have an excellent educational system, with a particular aspect the US could stand to emulate. Education is free, and as long as your grades are good, continues to be free, even at the college level. As soon as you slack off and routinely fail to appear in class or neglect your assignments, you’re out. If you’ve had a change of heart and do want to continue your education, you must pay for private classes. This system ensures that even in poor villages, there are some who complete the formal requisites and become doctors, lawyers, teachers and other skilled professionals.

Mexico in general, was not an improvised country until the peso crash. It had a very large middle class; as large as our own was before our own devaluation of spending abilities. Most of my friends – and they were quite revolutionary – were well educated. Their religion wasn’t a hope they hung onto that somehow they would be mysteriously delivered from their plight, but as natural to them as breathing.

Although the people are predominantly Catholic, I actually felt a stronger sense of religious freedom in Mexico. They accepted any spiritual belief; metaphysical, paranormal, psychic or plain superstition, such as carrying a rabbit’s foot for good luck. The beauty of this acceptance was their consideration of the possibilities. If you felt yoga meditation would enhance your spiritual connections, they were perfectly willing to try a little yoga with you, or at least respect the environment for your meditation.

I see Americans as feeling they are at the mercy of outside forces far more than I do Mexicans. They avidly explore their minds and are willing to examine anything new to them without prejudice or suspicion. We don’t really know the mind’s full potential because we fear the exploration. We put up smoke and mirrors. We reject what we can’t place in concrete terms. We place more faith in outside forces; i.e., in material things and acquisition, than we do our own abilities. In such a scenario, religion easily becomes more of a crutch or a tool to bend the will of the people, but this is not what I saw in Mexico. I saw a people guided by their own faith in themselves and each other, who just happened to be religious.

[…] idea of a new family addition, began calling him our lucky charm. Then, the … Read more on Subversify If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it! Tagged with: Charm […]