By Karla Fetrow

We all know the stories on how the west was won; the gunfights at OK corral, the legendary Wyatt Earp, Doc Holiday and others who braced the forces of lawlessness to bring law and order. The wild, wild west was tamed at the point of a gun, and frankly, so was the wild north. The history books, the movies, the television shows all depict honest but helpless homesteaders who could never have survived without the western heroes brandishing their badges and cleaning up the mess the murderous bandits left behind. Credit should be given where credit is due, and there is no doubt there were some very courageous law men putting their lives on the line, but when you consider the political arena, the enormous greed, and even the apparent willingness to solve all disputes with violence, it becomes a little dubious that civilizing the west was due entirely to the gun slinging tactics of a few lawmen. The books, the movies and the television shows fail to characterize the strength and determination of the early homesteaders.

Homesteading, signed into effect by President Lincoln, was on the wane by the early 1900’s as the the generous land parcels that initiated the homesteading surge into the west dwindled with individual claims. However, under the New Deal, signed into effect by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1936 to develop and invigorate rural areas, also opened up the vast Alaskan wilderness for homesteading. It was more than a New Deal; it was a new hope for farmers, blue collar workers and others who had been struggling under the yoke of the Great Depression.

While it can’t be measured in the thousands that migrated into the far more temperate climate of the western United States, the hundreds who came faced very similar obstacles. They were faced with complete wilderness, with no road systems beyond one rudimentary highway. For those of European origin, their only European counterparts were basically miners, trappers and a few scattered military outposts. They obtained their land through government contracts and policies and were expected to develop their townships by the same policies. As far as law was considered, however, they were basically very much on their own. There was one basic difference; the United States Government had quit waging war against the Native American populace by then, so there were no angry tribes seeking revenge. Although the setting for their homesteading efforts had a far more brutal natural environment, peaceful settlement came with a lot less effort.

They were, however, faced with lawlessness. Not everybody welcomed the new influx of settlers and the laws they brought with them. As with the west, many of the skirmishes were over land claims. By law, if you applied for a homestead and received your patent, or paid for a homesite claim, there were a few things you had to do to remain in compliance. You must clear a certain percentage of your land for farming or settlement. You must build a home and remain there for at least six months out of the year. While most complied with this law, there were still a few who resented any intrusion on the right to do as they pleased, and anywhere they had placed a stake was their, whether they filed with the territorial government or not.

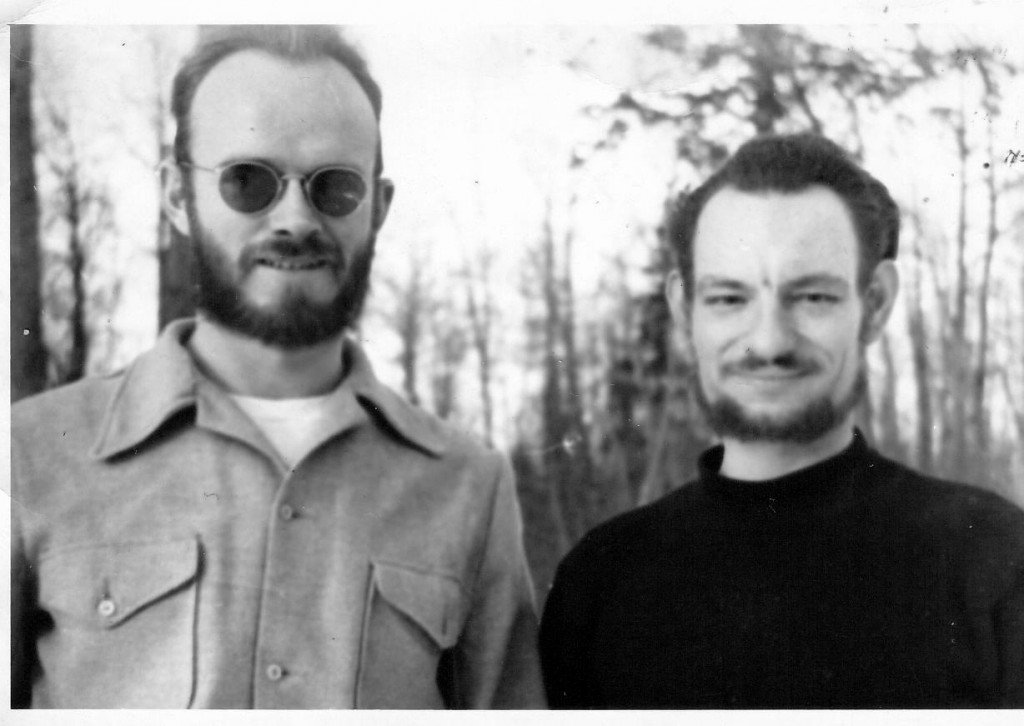

Les came to settle in Alaska in 1946, although it was not his first exposure. He had joined the Civilian Youth Corps under the New Deal provisions when he was just seventeen, and had been assigned to bridge construction in Ketchikan. As he explained to his young wife, he had been struck by the beauty of the land, and wanted nothing more than to return to it. His opportunity to return came only after a terrible World War and now his greatest ambition was to put that war behind him and create a family that would hopefully never see such ravages again.

They rented a small cabin in a settlement that had, at the time, only four other families. His landlord ran a grocery store, a laundromat and handled the local mail. It was the only center of activity, but it was kept lively through nightly story telling, a bit of impromptu music, and occasional skits. It was there he met Paul, who told him about a piece of land up for sale next to his homestead. A trapper named Jake had put up a shack, he said, but had never filed his claim and hadn’t returned in five years. “Frankly,” said Paul, “the man is shiftless, has no respect for others, and harasses women. I have two small children and I’ll be glad if he never comes back around.”

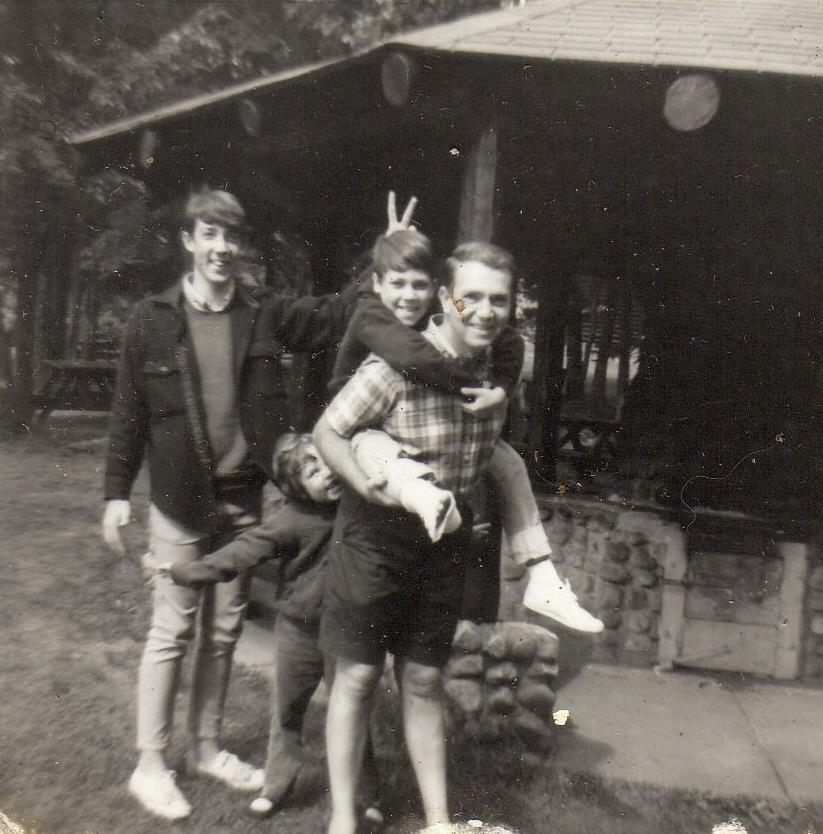

Les looked over the five acre plot, decided he liked what he saw, and filed a claim on it. Within a year, he had cleared twenty percent under the terms of the contract, built a house, and had chickens and a garden. He also had two small children, and another on the way. The settlement was growing just as quickly. There were now ten families that stayed in touch with each other through old military hand cranked telephones. Times were hard, but life was good. He had come to feel a sense of belonging. Then Jake came back.

Jake was furious to find someone had taken over the land he had regarded as his own. He gave Les a week to get off his property, and promised dire consequences if he didn’t. Les waited until Jake had left, then called up Paul. “Let me know if he comes around again,” Paul advised. “We’ll be ready.”

Les sat out the week, and the next, then the next. One evening, he saw smoke rising from the chimney at the old shack. Cradling his rifle, he watched as Jake walked up the drive, his own rifle slung over his shoulder. “I thought I told you to get off my land,” said Jake without preamble.

“It’s mine now,” countered Les. “I cleared it. I worked it. I paid for it at the claims office.”

“Then I suppose there’s nothing more to talk about,” said Jake. As he aimed his rifle, he heard a click behind him, then another. As he turned around slowly, four men stepped out of the bushes, their guns pointing at him. Jake surrendered then, and never returned, except maybe once in awhile for an overnight stay in the old shack, but as long as he never bothered anyone, no one bothered him.

The point of the gun was the common law in those early days. As the settlement turned into a community and the community into a small town, more disputes were settled by a show of guns than by calling the highway patrol. Funny thing was, you never really heard about shoot-outs and killings. If the people had taken the law into their own hands, it was a respected law. A road was as long as the inhabitants said it was, and you just accepted that. If you dumped garbage alongside of the road or trespassed, you could expect potshots flying over your head.

They weren’t saints. Taverns went up and from them, you could hear loud music and laughter far into the early morning hours. For every tavern that went up, so did a church, yet the two existed peacefully side by side.

The pipeline days rolled in, bringing greater prosperity, vigorous growth and a new breed of people. Suddenly, there was violence, more inexplicable and brutal than had ever been witnessed before. Suddenly, there was murder, not just the kind you see on television, but among the community’s own. It was mind numbing. The streets that had always been safe were now no longer safe. The stranger you once reached out to and helped was now the stranger that could harm you.

This new breed also brought with them a new type of law and order. Nothing brought it home more explicitly to the community than the incident on Edmunson Lake. Jess and Neva lived on Edmunson, which was a good ten miles from any other neighbors. They had a small cabin, but a small cabin was all they needed to be happy. Jess was a hard working man with a bulldozer. He was also a jack-of-all-trades. If somebody needed their land excavated, they called Jess. If a plumb pipe burst in the winter, or their care wouldn’t start, they called Jess. Most of the time it seemed he worked for free. It was said if everyone had paid him that owed him money, he would have been a millionaire, but he wasn’t. He was just a modest man with a small cabin.

Neva was beautiful; with that stunning, red-haired type of beauty. She was more of a fun-loving type of woman than she was a homemaker, but she served well as a hair dresser, a nurse and the most desirable waitress to have in a restaurant. Neither were the type to bother anyone, but one night a few somebody’s decided to bother them.

It was late in the evening when they heard some teenaged boys whooping it up and getting drunk by the lake. At first, they just ignored them, but after awhile they noticed the sounds were getting closer and closer to their cabin. Jess stepped outside and noticed the boys had torches. They were still a good distance away, but rapidly moving in. He ordered them off his property. They ignored him. One of them shouted, “what cha gonna do, old man?”

They laughed and pushed each other as they stumbled through the brush. Again, Jess ordered them to leave, and one of them threw his torch. It caused a small burst of flame, but the ground was soggy and the fire quickly went out. Jess reached inside his cabin for his rifle. “I’m asking you politely to leave,” he warned them. If you don’t, I’ll fire.”

They didn’t believe him. Laughing, they continued to advance. Jess fired. He had meant to shoot over their heads, but the evening was thick and the lighting was poor. He shot one of the boys in the chest.

The rest of the boys took off like the devil was on their tails, leaving their companion bleeding on the ground. Neva ran out of the cabin sobbing, and carrying a towel. She wrapped it around the wounded boy’s chest, applying compression while Jess started up his truck. They had no phone, no electricity and were ten miles from the nearest neighbor who could help. They drove the boy as fast as they could to the nearest emergency center, while Neva cradled the boy’s head on her lap, whispering over and over again, “please don’t die.”

They were too late. The boy died in the emergency room. A couple hours later, the police came by and hauled Jess off to jail. The community was shocked. This was one of the kindest, most upright men in the entire town and he had been placed in jail! There were letters, protests and visits to the judge. Several days later, the judge backed down on pressing charges and ruled it was self-defense, but it was also a message. No longer were they ruled by common law. Another form of law had taken its place.

The years have passed. It’s no longer a community that stands by each other to sort out differences and ease troubled waters. New people move in and complain about their neighbors, calling the police when they feel irate. The old timers are moving out, looking for more remote areas where they do not have to put up with constant interference in their lives.

Looking at today’s troubled society, I can’t help but wonder if this is what we are lacking; the right to build and choose the direction of our communities. We do not have trials by our peers and colleagues. We have trials by strangers who know nothing about us. We do not have judges who examine carefully each person’s case, understanding the circumstances and mitigating factors. We have judges who decide whether or not you have committed an infraction and the penalty you must pay. We are ruled violently and abruptly, so that instead of easing the anger, it pressure cooks and seethes. We are ruled by the point of the gun, but the gun is not our own. Common law has shifted into a thing of the past and all we are faced with are strangers who do not know or care who we are.

By and large, these folks sound like my kind of people – I don’t like the idea of “paying claims” to anyone (as I see land as something held onto by strength, not through investment of state-backed IOUs to some external power), but I more or less embrace the value system these people do: if you stake your claim, you work your land and have the power to keep others off of it then it belongs to you!

Azazel, i pretty much agree with you, but you have to consider these were a people from a different time era. Despite having gone through the Great Depression and a World War, they still believed in their government, and were quite happy to follow the stipulations of the Homestead Act. I’m sure they never once imagined the government they supported would one day turn on their own children.

Mitch, i hear you loud and clear. One of my friends commented, “an armed society is a peaceful society.” This is very true. When a community stands together to protect each other, the bullies think twice about saying, “what cha going to do about it?” They know perfectly well what’s going to be done about it.

I think society is becoming more violent because there is too much interference. Instead of simply allowing groups to live peacefully together, they are invaded by a law enforcement that tells them how things have to be done, that forces them to live by laws they never asked for and never agreed upon. We don’t need that. We need to be able to feel we have direction of our own lives, that we are capable of making our own choices. If our choices are so bad, they are doing harm to others, an armed society would quickly straighten those choices out.

Mitch brought up an excellent point. While those who consider themselves “Liberal” often go about decrying Guns and Weapons, the do it is such a bully-like fashion- seemingly missing the irony of their own bully tactics. It amazes me that they even keep the tag of liberal when almost nothing they support promotes liberty.