For a gentle summer and an incredible autumn dawdling nearly a full month longer than usual, Alaska is having a voracious winter. Beginning with a powerful storm that churned the Chukchi Sea with hurricane force winds and freezing weather, it seems the personality that encompasses Alaskan climate has been snarling, “no more Mr. Nice Guy”.

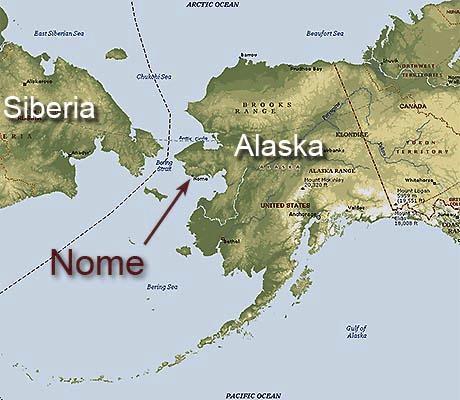

The storm surges were as high as five to seven hundred feet on some of the Western Arctic coastline, driving temperatures down to below zero from Barrow to the Cook Inlet. The cold snap lasted nearly an entire month, with colder than normal temperatures recorded throughout the state. The town of Nome was faced with another dire hardship. The vicious storm had made it impossible to bring in the last barge of fuel oil and gasoline for its residents. A snap freeze a few days following the storm had seized the Chukchi Sea prematurely, closing the shipping lanes, and the last scheduled shipments were unable to force their way through the ice.

The distributors in the town estimated that they had enough fuel to make it through March and possibly April, but the sea would not be navigable again until May. Without the additional fuel, they would have to ration their consumption by limiting their vehicular use and lowering the heating temperature for their houses. If the winter was good, with its traditional temperatures of five degrees to minus three, they would be fairly uncomfortable, but not desperate. However, there was one thing the locals all knew; never predict Alaskan weather. There needed to be a way to bring more fuel to the town in case the weather didn’t remain traditional.

Another barge company, Delta Western, had slated a September delivery of the 1.6 million gallons of fuel, then rescheduled for a couple of arrivals in October, according to Nome port commissioners, when the Alaska coast was ice-free all the way to Kaktovik on the Beaufort Sea. However, the November 8th storm halted their journey and they had to turn back.

There seemed few options for the town of 3,500 inhabitants who yearly hosted the finishing line of the Iditarod Dog Sled Race. Nearby communities were already feeling the pinch of the early cold snap, and their own fuel supplies were beginning to dwindle. To fly in a million gallons of gas and fuel would be risky and expensive. It was estimated that to deliver the gas by air, the price, which was already nearly seven dollars a gallon, would soar over nine dollars a gallon. No American company felt they had the ship that could make the delivery. When Russia offered to deliver to Nome, with their tanker, Renda, the Native Corporation, Sitnasuak, was ready to accept.

From the very beginning, the Renda was burdened with obstacles. The Renda had to receive waivers from four different countries to pass through their waters, including a special waiver of the Jones Act that requires all goods transported by ship between US ports be carried in US flag ships.

The 370 foot ice class tanker left Russia in mid-December and picked up more than 1 million gallons of diesel fuel in South Korea. When a plan to pick up gasoline in Japan didn’t work out, the ship received a waiver of federal law allowing the foreign vessel to dock in Dutch Harbor in the Aleutian Islands, where it picked up 300,000 gallons of unleaded gasoline.

In the meantime, Alaska’s weather was anything but traditional. December began a series of storms that broke snow fall records on the western coast from Nome to Cordova. The Anchorage Bowl accumulated five feet in a matter of days, while parts of the Kenai Peninsula closed down their roads while they cleared them. Avalanches covered the Turnagain Arm, stranding Girdwood for a week. Further south, Valdez, the great snow fairy land of Alaska, was buried under nine feet.

Cordova took the main brunt. After receiving more than fifteen feet of snow, it gave up on trying to measure the continuing snow fall. It had arrived at a moment of intense crisis. The towns people were desperately trying to dig their way out and remove the heavy accumulation from the roofs of their homes and public buildings while gales roared across, sweeping more snow into their paths. All able bodied people were working, but they ran out of shovels. Additional snow moving equipment was flown in and the fight continued, but at times, it seemed like a losing battle. Roofs caved in. Boats keeled over, damaged or crushed by the snow storm. Many of the residents were forced to seek emergency shelter.

Nome’s hope for a traditional winter was shattered by early January. The heavy blizzards that dumped record snow falls in Cordova and Valdez also broke their snow fall records when three back-to-back storms dumped 17.5 inches of snow on the town and surrounding area, making it the wettest December in 60 years.

The December precipitation was followed by plunging January temperatures, once again throwing the entire state into the grips of sub-zero temperatures. Nome’s coldest day, on January 3rd. with -37F tied the record for cold weather that had not been broken since 1917. Nome was shivering now, and the success of the Renda, which had at first seemed just a wise precaution, became crucially important for the Arctic town that would not see another opening in the ice until May.

In the meantime, the Renda was battling with its own difficulties. On January 6th. the tanker that had navigated around four countries and had been told it was too puny to dock in Japan, had to turn around in the Bering Sea because of a faulty valve. The local residents held their breath as the Renda docked in the Aleutian Islands. The Coast Guard had only one functioning ice breaker to help the heavy tanker plow through ice that was two feet deep in some places. There were three hundred miles left to go, on the most brutal expedition yet undertaken in the twenty first century. Would they make it, or would they be iced in, forced to abandon their project until spring? The Renda announced it would continue its journey.

The Renda plowed ahead, with the Coast Guard Cutter, Healy, just in front of it, slicing a path through the ice the tanker could follow. Their efforts could be called nothing short of heroic. There were times when the ice was so thick, and the weather so cold, the ice immediately began re-forming as soon as the Healy cut through it. The unyielding ice billowed and swelled in the sub-zero temperatures, crushing against the Russian tanker, sometimes pushing it from its path so that it would have to re-navigate its direction. At times, the Healy and the struggling tanker were able to crawl at just a few miles a day, its progress so slow, a person walking over the frozen sea would have overtaken it.

On January 14th. the Renda was, finally, just a few miles from Nome and looking for a “parking spot” in the uncooperative ice. The days of excruciatingly slow journey wasn’t understood very well by the pondering public, but the native population, so familiar with the Arctic Sea, understood the difficulties involved. They even have names for the different types of ice conditions. Said Mayor Edward Itta in a correspondence with Captain Carter Wilson as reported by the Alaska Dispatch:

‘Siku iluaqsilaaga‘ – means the ice is not cooperating.

‘Siku tatiruq‘ – the ice is very tight; not loosening (sometimes because the ice has formed or piled on itself in such a way that it becomes interlocked).

‘Siku nuutqanaruq‘ – the ice is stopped; not moving.

‘Saqviatchuq‘ – no current.

‘Iikalginnaruq siku‘- the ice is stopped because it is grounded (by ice ridges that are deep enough to be stopped by grounding on shoals or shallower water).

‘Siku nutqanaruq saqvaq suammigluni naga iluitgluni’– the ice is not moving because the current is too weak or from the wrong direction to move the ice.

‘Annugim aqmatinnitka‘ – the wind or lack thereof or blowing from the wrong direction is not favorable to opening the ice, etc..

The captain jokingly asked if there was a term for when the ice was being nice. Nice or not, the Renda found a place to port in the treacherous ice rubble of the Northern Sea with the guidance of the local community. The final step was underway; transporting the fuel to the coastal town. The difficulties were not over yet. It was now a matter of transferring the fuel without spilling it. The organizers for the transfer had already anticipated this, and had prepared a system whereby a hose would be attached between the tanker and the dock.

The captain jokingly asked if there was a term for when the ice was being nice. Nice or not, the Renda found a place to port in the treacherous ice rubble of the Northern Sea with the guidance of the local community. The final step was underway; transporting the fuel to the coastal town. The difficulties were not over yet. It was now a matter of transferring the fuel without spilling it. The organizers for the transfer had already anticipated this, and had prepared a system whereby a hose would be attached between the tanker and the dock.

This procedure involved a number of precautions. First, the tanker needed to sit in its spot, so the ice could form rigidly around it. This would preventing tilting or rocking that could result in a fuel spillage. Environmental Protection laws required they could only work in daylight hours. In January, Nome has just five hours of daylight per day.

On January 17th., the fuel was finally running through the two parallel, seven hundred foot hoses. Senator Lisa Murkowski, along with a number of other state representatives, flew into Nome to celebrate the successful mission and congratulate each other on it. The truth, however, is that the State of Alaska had very little to do with the Renda’s journey apart from clearing the paperwork obstacles and providing an ice breaker. The entire two month labor of will and determination had been planned, financed and organized by the Sitnasuk Native Corporation.

The journey of the Renda was incredible, a modern day illustration of the little engine that could. It brought out the best in human qualities; inner strength, bravery in the face of adversity, cooperation, integrity, diligence and unflagging commitment. It had done something that had never been done before; cut through the unforgiving, unyielding ice of the Arctic Sea to bring over a million gallons of fuel to a far northern coastal town.

The journey of the Renda was incredible, a modern day illustration of the little engine that could. It brought out the best in human qualities; inner strength, bravery in the face of adversity, cooperation, integrity, diligence and unflagging commitment. It had done something that had never been done before; cut through the unforgiving, unyielding ice of the Arctic Sea to bring over a million gallons of fuel to a far northern coastal town.

It also, subtly, raised the question of human behavior. When the tanker first began its journey, many of the citizens in the warmer, more comfortable climates, with a solid grid work of road connections and plenty of fuel, criticized its efforts as an unnecessary burden on the tax payers. The tax payers had not paid for it, and if they had, another question raises to the surface. Nome, along with Kotzebue, is the lifeline for the Arctic villages that often struggle through the winter with repeated fuel shortages and an economic base that does not always allow them to pay their energy costs in full. It is rich in history as one of the earliest gold rush towns, a rush that opened the door to settlement and statehood. Most importantly, it is part of the network of towns and villages that comprise the State of Alaska as a whole. Thirty five hundred citizens or twelve thousand citizens; each town and village deserves the umbrella protection of winter survival.

While Russia continues to be looked upon with distrust by Western media, it has proven once again to Alaska it can be a good neighbor. It made a promise and it delivered, despite the obstacles placed in its path, despite the criticism of its slow progress. It put aside any political differences it might have to be of assistance without asking how long it would take, or how great the difficulties it might anticipate. The State of Alaska warns that it’s not over until the Coast Guard cutter has safely returned to port and the tanker has been dispatched to Russia, but for many joyful Alaskans, it is over. The impossible task had been made the possible. Fuel was running through their pipes. They could look forward to another fine Iditarod, with a warm welcoming committee instead of shivering fans and cold shelters. They could ride out the next three months of Alaska’s decidedly non traditional winter, without worrying about losing their fuel before spring thaw. The only thing left to do was heartily thank Russia for being a neighbor, a friend.

http://www.adn.com/2012/01/09/2253848/thickening-ice-raises-worries.html#storylink=cpy

http://www.alaskadispatch.com/article/update-renda-final-position

Some good news for a change.

But… I can see Russia from my front porch! Yep, there’s a dog named Russia across the street. Well, that might be his name. I don’t really understand Spanish too well, except for the cuss words.

LOL, Space Eagle. I sometimes feel sorry for Palin as she uses a lot of colorful Alaskan expressions without really reflecting on their meaning. Her home in Wasilla isn’t even on the coast, which would make it extremely difficult for her to see Russia, but the truth is, we have Russian communities all over Alaska, so in a sense, we do see Russia from our back doors. On a very clear, cold day, the most northwestern coastal points can in fact see the coastline of Siberia shimmering in the distance.

Even during the Cold War, Alaska had no real quarrels with Russia. The main anxiety was that the US missile bases placed near our towns would be a target. In fact, we’ve had more explosive arguments with Canada and Japan over fishing rights than we’ve had squabbles with Russia. We have much of the same demographics as Russia. Most of our climate is harsh, as is theirs. Most of our people are rural. Russia has some large cities clustered near its southeastern borders, but the large percentage of its towns are small and rural. Russia shares the same fish and wildlife, the same natural resources. Trade back and forth from Russia has been going on for two centuries. The Inuit people have cousins and brothers and grandparents in Russia. For centuries they’ve crossed the winter’s frozen sea to visit them.

Russia isn’t evil. It’s full of the same wonderful people you would find anywhere. It’s full of thinkers, inventors, artists and musicians. It’s full of laughter to keep a cold day warm, strong backs to brave the forces of nature, and conversation to lighten a campfire. I think the more we put aside our imagined differences with Russia, the more we let go of our fear that its a monster filled with vicious cartels, the more we allow ourselves to listen to them, the more alike we’ll find ourselves to be and more determined to enter the new age without war.

Yeah, Alaska used to be an Imperial Russian colony before the idiot Tsar sold it to the US.

Well the “Idiot Tzar” sold it to feed his starving people which is something a Monarch should care about-However, it no longer seems so. But, family is family…Yes? And the Russians seem to remember that better than The State Government did. BTW, so did South America, they just couldnt get through.

I think the Tzar’s decision to sell Alaska might have had a lot to do with prudence. The fist shakers of “infidels” were roaring behind the Monroe Doctrine, taking an unkind view of Eastern influence on the Northwest American seaboard. They had already pretty much booted out Russian settlement in Washington, Oregon and California. They were riddled with anxiety over the spread of the Russian Empire into Alaska and probably would not have hesitated to declare war in order to put an end to it. Selling Alaska was the cheap way out.

In some ways, Russia won. They left behind a culture that had already been educated in Russian schools, converted to the Eastern Orthodox religion, and were well integrated with Russia through marriage and employment. The early American settlers found a people that had already adapted to one culture without tremendous risks to their own, and were easily absorbing the American pioneer culture. This adaptation became a distinct feature of Alaskan settlement and continues to be an astonishing aspect of its growth. No matter where a person was originally from, after a few years in Alaska, an attitude is developed of “we don’t care how things are done there. This is how we do it here.”

This attitude is giving it sharp characteristics and i can see it becoming its own country, choosing its ties and alliances. It’s probably only a matter of time before even our legislators will begin reconsidering the advantage of being a state.

What a great post!