Twenty Years of Change

November, and winter has moved in, solidly creaming over the landscape with a thick layer of snow. The earth and sky meet in a single blurred testimony, leaving only the trees and the houses to mark the boundaries of earthly and celestial visions. The termination dust gathered late; much later than childhood muses remembered. A friend who hasn’t visited Alaska since he left over thirty years ago wrote telling me he remembered how, in the midst of fishing, hunting and harvesting during the summer, the first light sprinkling would gather on the mountains, announcing the approach of winter.

Funny how quickly memories can fade when you are a part of the continuity of changing seasons. Thirty years ago autumn began around the same time as school started, in early September. The leaves turned rosy or bright yellow in their preparations for winter. The mornings were frosty and the evenings, crisp and clear. They were rewarding times; a time between seasons. A time to take the load of your back awhile. Soon enough, the vegetables canned or frozen would be brought out to compliment the dinner table. Soon enough the smells of baking would fill the house as frozen rhubarb and berries were made into pies or served on pancakes. Soon enough the pile of split wood in the shed would be used and in the blue dusk of morning the axes would ring as they snarled into the piled rounds. For a few short weeks, the work was finished.

When the winter came, there would be other challenges. Keeping the driveway plowed, the automobile running, rescuing friends from a ditch. People often remark how Alaskans all seem to have broad shoulders. This is because from the time they were seven or eight years old and had at least sixty pounds to lean with, they were initiated into the arts of successful car pushing. These aspects haven’t changed much over the years. Outside the City of Anchorage, life styles are still highly subsistence based. With the first heralds of spring, seeds are nurtured in window sills, the snow is dusted away from garden patches, the long routine of filling the potholes in private driveways, of clearing the yard of winter’s debris, of preparing the groundwork for new construction begins. The mechanics are tinkering under their cars. The back hoes, the tractors, the bob cats, the loaders are brought out, their engines cleaned, their tires patched. Fishing poles, dip nets, fly rods are unloaded from the closets and the tackle boxes refurnished.

Yard work in a rural home is a summer long activity. Alaska has some of the fastest growing and most aggressive plants in the world. Within a week after the last of the snow is gone, the weeds come up. Alder, willow bushes, devils club can be cut to the root and still grow back to four feet tall within a month. Fireweed grows over six feet tall. A freshly paved road will show weeds pushing through the cracks before summer’s end.

What has changed is the climate; so delicately that the changes have seemed almost imperceptible. In 1990, I returned to my home in Alaska after a ten year hiatus in Mexico. It was early July. The family said we were having a spectacular summer, with warm sunny days temperatures in the seventies. But on the near mountains, there were still patches of snow, rivets and gullies we had always considered a permanent factor. The breezes blew gently down from the mountains. I could feel their snow melt, their icy promise of winter. I shivered.

Winters’ first snow fall came in early October. The years spent away made me feel like it had come too soon, yet my memories chided me. By Halloween, it almost seemed pointless to put on costumes as the snow was usually knee deep and the temperature sitting around zero. The costumes were stuffed inside snow clothing and boots, with only our make up or masks proving we had put out the effort to wear a disguise. Time had preserved the image of the environment, but had erased the memories of the cold.

It didn’t take long to get those memories back. My first year home, I lived at the end of a three mile off-road that received very little traffic and no state maintenance. My cabin was heated with a wood stove. As the days grew colder, I stayed up later at night, feeding the fire, and waking earlier in the morning to stoke it back up.

Each snowfall presented new challenges to my driving skills. A wet snow meant a thick, icy glaze over the road, full of slush that clumped and knocked inside the tire wells. A pile of light, fluffy snow meant very little traction, sleet meant it was better to simply put on ice skates. There wasn’t really any such thing as holing up until the bad weather was over because blizzards, snow flurries and white outs were part of everyday winter life.

I spent about as much time getting myself out of a ditch as I did going up and down that three mile road. I learned a new trick with my tire jack. It wasn’t just handy for changing tires. When a wheel dropped over the edge of the road, burying one end of the car up to the axle, I’d bring out my jack, crank up the offending end, lean against it and push it over. Sometimes I’d have to repeat this exercise two or three times, but eventually my car would be back on solid pavement. My childhood pushing muscles were becoming rather well developed.

By the second winter, I had traded my heavy bodied mid-eighties Malibu in for a much lighter Ford Tiempo. My brother, the mechanic, sneered about it, calling it a tampon, but there was one advantage to this otherwise nondescript machine. I didn’t need my car jack. If it plowed into a bank, and it did so with greater aplomb than the heftier sedan, preferring to bury itself up to the windshield than sink a wheel rigidly into a ditch, all I had to do was put it in neutral, jump on the bumper a few times, and I could usually loosen it up enough to drive out. If I had an adult passenger or two with me, we could just about lift it out.

Entering the Decades of Bizarre Weather

There was some talk about global warming back then, but it was basically idle speculation. There wasn’t any real evidence other than some rapidly shrinking glaciers. The winters came promptly, in early October and reluctantly shrank away by mid May. But, beginning with that first summer when I returned, described as spectacular, a new pattern began to emerge. The normally overcast days became less frequent. The sunny days would roll over, one into another, in stretches of a week or two at a time, with each clear day nudging the temperature a little higher. It was almost as if the sun streaming down in rustling waves was trying to show just how spectacular it could be.

My second year home, the returning sun of spring was so enthusiastic, it was sixty-four degrees by mid-April. This was extraordinary for a climate that rarely saw more than fifty degrees throughout the entire month of April, which was often included in the winter months, as it could turn treacherously cold or snow at any time, but that year it didn’t. What was even more extraordinary was that we had accumulated nearly nine feet of snow that winter. The snow had only just begun to melt when the sun decided to do its warm up dance. It cast a brilliant, uniform sheen over the covered landscape, a sheen that looked liked like a smoothly rolling ocean of diamonds.

It was an invitation to play my six year daughter could not resist. She dashed off the main trail and into the undisturbed snow field; immediately sinking up to her neck. The rapid change from winter to spring’s first kiss had melted the snow pack just under the glistening blanket. She was literally swimming in snow. Regina had been learning English ever since we’d first arrived, but in her surprise and panic, she reverted to her native language. Her cries of “ayudame! Ayudame,” caught my immediate attention. The slush and water rose up around my waist as I waded in to assist her. I had to break into a bit of a swim myself in order to grasp her hand and pull her into safety. Yes, Virginia. In Alaska, you can drown in mud puddles.

That summer heralded a stint of week long eighty degrees weather. The locals were enthralled. Eighty degrees was an occasional luxury that happened when nature was being especially nice; a day or two to notch away in the mind as to what paradise really feels like, but a week long was just something we entertained in our dreams.

The most peculiar aspect about that year fading so quickly from memory as even more peculiar years took their place, was that when the more typically cooler days of overcast skies and rain took its place, the change was announced by thunder and lightening. Thunder is relatively common on the Cook Inlet, but not lightening. Lightening appearing in the sky was about as likely as, well; being struck by it. The odds just weren’t in its favor.

But that year, and during subsequent ones, we began witnessing lightening storms. As the dramatic cymbals of nature announced the weather change, huge black clouds rolled in, slamming against the mountains. We didn’t receive the usual sprinkles and drizzles that announce the beginning of our rain season. It poured. It rattled on the roofs for hours before settling down to the normal patter of our summer rain. It became normal, after a few years, and speculation died down as to whether or not we were experiencing global warming. After all, our winters were still cold. Never mind that a few summers later, we had record breaking hundred degree temperatures in areas that rarely had a high of over sixty-eight degrees. The thermometer still dropped below zero by November.

That was before we had a series of winters so bizarre, we had names for them. There was the undecided winter. The first frosts came at their normal times, midway through September, with a respectable blanket of snow by late October. Then, just when it began to drop down to zero, a warm snow storm came in, mixed with sleet and rain. Another cold spell hit, followed quickly by another rise in temperatures. The rapid rise and slide on the thermometer became the pattern of the entire winter, sometimes dropping or climbing to extremes of forty degrees in a matter of hours.

Then there was the pie avalanche year. The snow was particularly enthusiastic that year, burying barely frozen ground with a few good feet before the serious cold set in. The cold spell was long, creating a thick crust of hard pack over the soft layer underneath. When it broke, it brought freezing rain before delivering another foot or so of snow. Another cold spell came, freezing the new upper crust, followed by another snow storm. The layers of snow and icy hard park built up. By February, the thick accumulation of termination dust teetered precariously on the mountain tops. With the first warm touch of sunlight, the snow resting on its slippery ice slope began tumbling down. As each layer was warmed by the strengthening sun, it tumbled like the filling of a pie turned sideways. Nearly every snow covered mountain top in Alaska avalanched.

In first place, was the winter that never came. Even the youngest Alaskan who was more than a toddler at the time, remembers it. Sometimes the frost came, but it melted away in a rain storm. By November, new grass was springing up from the exposed ground. It wasn’t until Christmas that we received our first snow, but it was mixed with sleet and rain. January, our coldest month, basked in thirty degree weather. March came to remind us it’s still a month of unpredictable, wintry weather, but by then, spring was firmly on its way. A winter that lasts only a few weeks is not a winter at all in Alaska.

The victory cries of global warming were very short lived. The next few years seemed to see a return to normalcy for Alaskan weather. The typical overcast skies returned in the summer, with spells of sub-zero temperatures in the winter, and the term “global warming” was carefully crafted into “climate change”.

When You Know There Will be no Reversal

Memory, so fickle, so willing to be altered, however, didn’t pick up on the subtle changes. Eighty degree weather had become so common, the locals complained if there weren’t at least a few remarkably hot days. Autumn moved in later and later. The pumpkins that were typically carved and placed out on the porches in early October, waited until the week before Halloween as more and more often the pumpkins rotted before the holiday instead of remaining frozen in place. One of the more notable differences was in the use of the yearly permanent funds. Usually distributed in the first week October, the most common uses for the bonus was to take a vacation, pay winter’s high energy bills or save it for Christmas shopping. But, with winter coming in so late so often, people began hedging and crossing their fingers that the ground would still be warm enough for just a little more construction. Often, it was, and then there would be an extra flurry of work activity as sheds were built, porches finished, the new well settled in. More and more, the dividend was used for land improvement instead of vacations and shopping.

Elementary science teaches you that white reflects back light and black absorbs it. This basic principle applies to the science of permanent snow coverage. The more the glaciers, fjords and snow caps melt, the more dark earth is exposed to absorb the heat from the sun. Last year, an astonishing thing happened. The summer, that had been so typical, was accompanied by warm rains that extended well into September. At the end of the rain season, a strong wind blew in, straight off the Inlet, much warmer than our usual north-westerly gales that herald in the winter. When it was spent, every bit of snow that had in the past, always decorated our high mountain tops; was gone. It had been dwindling steadily for years, greenery spreading up bare rocks that had once been covered with snow, but now there were no ribbons of white, no tidy blankets at all.

The changes have been slow, so slow they blur and what had once been considered unusual now feels normal. While other parts of the world alternately suffered between drought and flood, Alaska enjoyed a beautiful summer. It came in gently. The ground had not frozen completely before the first snow so as the snow melted, it sank, drying the mud puddles more quickly than usual. By mid-May, the leaves were furling open and the grass was over-taking the bare earth. The rains came evenly in between long spells of sunny weather. The long rain season, which usually lasts at least a month and generally comes in July, held off until late August. When the sky cleared near the end of September, it was as warm as an August day. There had been no frosts, no freak snow flurries, no sudden drops in temperature.

Construction crews that had worked frantically all summer to meet a cold weather deadline, idly filled in ditches, brushed off bike paths and added touches of black top to the roads. Yard work was carried through until there was absolutely no remaining interest, and tired bodies began to yearn for those vacation days of cozy fires and hot coffee, with nothing better to do than stay warm. Bicycles, usually put away by now, pressed for one more day of recreation, than another and yet another, the cyclists basking in the amazingly long autumn. Each day, the locals looked at the mountains, waiting for that telling coat of termination dust that would announce winter was creeping down and would arrive in the lowlands within two weeks. Yet September rolled into October and the mountains stayed bare.

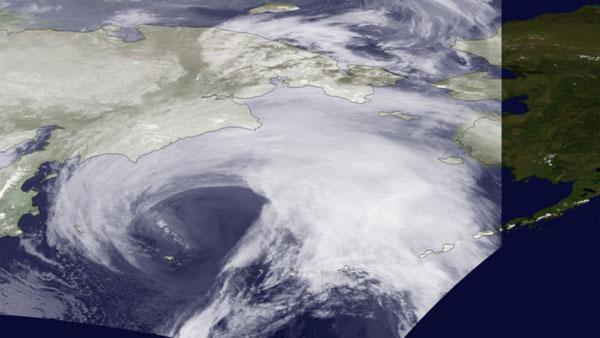

Winter finally came to us on Halloween. The sky clouded over. The temperature dropped. By evening, we had our first layer of snow. It seemed our weird weather had settled back to normal, but this wasn’t so. A massive storm front of hurricane proportions moved up the northwest coast toward the Chukchi Sea on November sixth, causing a statewide emergency alert. It wasn’t the size of the storm front that worried the residents, although it was one of the most massive on record, or even the winds. At this time of year, the Chukchi Sea is usually covered with ice, but this year the storm hit open water. It was the storm surge that kept people sitting on the edges of their seats. According to the news broadcasts, at least thirty-seven communities experienced some fallout from the storm, ranging from minor flooding, to power outages, to residents taking refuge in school shelters.

The big scare turned into only a minor boom by Alaskan standards. As Alaskans shook their heads, laughing at the storm that drove them to buy extra supplies and prepare to knuckle down, they stated the one cardinal rule that all seasoned veterans go by; never, ever try to predict Alaskan weather. What we can predict is the climate will continue changing. Many of the villages slammed by the storm had already been suffering erosion over the last few years, with plans, but very few funds, for moving further back from the coastline. The Big Storm could simply be the prelude to other storms which, finding a new playground in open water, will alter the coastline, change the jet stream and create new bizarre patterns that will eventually be considered normal.

We adapt. One of the harshest climates in the world is gentling its hand, but in the process, will set the precedent for climate change everywhere. The question of the new era will not be how to reverse the effects already set in motion, but how to live with them. It will not be how to avoid natural disasters; drought, floods, earthquakes, tornadoes and hurricanes, but how to survive them. Nature is oblivious to status, gated communities, well protected homes. It doesn’t care about your religious denomination, if you’re a friend of pets, or harbor guns in your basement. It has only one question for you. When you meet it face to face in its full wrath, will you be prepared? The answer is, only if you are able to adapt.

[…] Subversify […]

[…] Subversify […]

[…] Subversify […]

This is poppycock! We had snow in Texas for two years in a row. We generally only get snow once every ten to fifteen years. That’s PROOF that there is no global warming…

…according to Texas Republicans.

Ha ha, Space Eagle, every time the temperature drops to zero, we have a few people who say, “where’s the global warming now?” Apparently, they believe global warming means the Earth’s temperatures will raise uniformly around the world, and all at once. Nor do they consider the effects of hot and cold displacement. An ice shelf that breaks away from the main continent in the region of Nova Scotia today, would meet the ocean as colder, fresh water, sinking to the bottom and changing the ocean’s currents. This cold current would then alter the temperatures in previously warmer areas; the contrast allowing snow to fall in Texas a year or so later; the main reason climate change presents a more accurate forecast of what will happen.

I’ve been studying the maps, trying to formulate exactly what this massive pressure system will do next. I don’t truly believe it has spent itself. Once a system has reached the Chukchi Sea, it has no choice but to bend and travel back down. Warm air pushed up into the Arctic, bringing a very temporary warm spell (twenty five degree weather) then cooled off as it traveled back down, plummeting us back down to sub-zero temperatures. It could continue moving back down the coast, cooling off Vancouver and even northern California; a mini sample of global warming followed by global cooling.

I must be getting old, or weather is really changing, or parts of my youth have long been forgotten by ‘others’. Having grown up in the 50’s and 60’s in Alaska I find this weather climate change very upsetting! August always found us looking up into the mountains – once the clouds lifted we looked for the snow; if it was there that meant next week it would be lower – winter was coming. There was something comforting and reassuring about that – we Alaskans knew what to do – the southern types did not and they feld south – we remainded thankful their noise had left. I still can see the first high snows on the mountians and it fills me with warmth – Winter Was Ours – not theirs!

Kenn, even ten years ago, Alaskan winters were specifically for Alaskans. Not now. Even film producers who used to do all their Alaskan plots in the state of Washington, are now moving their cameras up here in all kinds of weather. There is no longer avoiding rush hour traffic from Anchorage to Eagle River. Even during hours when there should be no flood, and with a four lane highway, there is a solid stream of traffic coming in and going out of both towns. We have begun to joke that it won’t be long before traveling between Anchorage and the valley will be like traveling between LA and San Diego.

I used to find our bizarre weather disturbing. Now i just see it as the inevitable effects of climate change. Maybe we could have done something about it forty years ago before the amount of greenhouse gasses began accumulating and our ozone layer depleted, but we didn’t and now all that is left is speculation as to how much of global climate change was man made and how much is nature’s cycle. Since we are changing, it doesn’t really matter who was at fault. What matters is what we do to prepare for it.

On another note, the storm did drive in about twelve inches of snow to the Cook Inlet. The dog mushers and snow machine riders are very happy, as are the snow plows that hear a ca-chink in their pockets each time they clear a driveway. We had a couple of years where there were no snow plow demands at all; only for sand on icy driveways; and the snow machine shops nearly went out of business.

Karla, having lived in my area of Northern California for a long time I can tell the differences as well. I wonder sometimes if because we as humans move so much and don’t set in roots, we tend to miss the small things that add up to change.

Nature will do what nature does but not only do we need to be on the watch for things like storms, etc. We need to be on the watch for how the changes can benefit our areas. Alaska already with a long summer sun may just be our new bread basket and protecting that resource for Alaskans is something that should be looked at.

I really enjoyed that, K. I notice you didn’t classify this as a travel log, but it’s actually one of my favorite travel related stories I’ve ever read. It paints quite a beautiful and yet tragic picture of Alaska, and helps to illustrate that global warming is a reality and is changing the weather all over the place.

Sure, there have always been earthquakes and wars. But the earth reacts to the environment that its creatures develop and has done so for millions of years. Just as it does today, only the ruination is so much greater today…just as the consequences will be.

And I’m very happy to know you’re safe 🙂

Grainne, i agree. The climate is changing and ignoring the significance will only bring problems that didn’t have to exist. Alaska does have the potential to be the next bread basket, but most of our law-makers only see our wealth in non-renewable resources and real estate development. Most of their real estate dreams hang in the Matanuska Valley, with some of the richest natural farm land in the world. Instead of encouraging the farmers, the real estate agents and banks wish to push them out and pave over their property with condos, apartments and businesses.

While we are getting warmer, some areas might find that putting in some cold weather crops will help boost their food supplies. Other areas that have been (and will continued to be) accustomed to frequent flooding, might wish to build a canal system to trap the flood waters for irrigation.

I think the greatest danger is to the coastline. Both the west and east coast are rapidly eroding. I’m sure this is true of coastal cities all over the world. While it isn’t possible for everyone to just pick up from their coastal home and move inland, a little emergency preparedness is smart. Keep a supply of matches or lighters in a safe dry place, and always on hand. Know how to make a fire without gasoline. Keep at least one flashlight and plenty of extra batteries. Buy a camp stove and make sure you have fuel for it. Keep a stock of canned foods and put dried foods in air tight containers. Learn basic first-aid, and keep a full first aid kit on hand. Learn how to walk at least a mile a day with a heavy back pack. Become familiar with hammers, screw drivers, axes and saws. Keep these basic hand tools in a safe place. Always have plenty of extra blankets and warm clothing, and put them in a safe, high place, preferably plastic wrapped. Be prepared to assist others. Hospital masks for air filters and buying a water container with a built in filter system is also a good idea.

Mitch, the storm kept our temperatures bouncing all over the place; dropping down to zero and climbing to the high twenties several times in a matter of a few days. I don’t doubt it’s busy traveling down the coast down to see what new mischief it can create. Climate change would not be so devastating if it didn’t mean it’s upsetting the entire stock pile of oil facilities and nuclear power plants. The industrial pollution is far more damaging than a flood or earthquake. If we stop stabbing the earth, she can begin to heal now, with us. If we wish to continue to be suicidal maniacs, taking as many with us as possible before going loudly into the night, she’ll just heal without us.

Thank you for that splendid post. I seriously like the website and thought that I’d let you know! 😀 Thanks a lot, really love