What have you done with the garden that was entrusted to you?

— Antonio Machado

By Eddie SantoPrieto

I had two fathers and possibly more. I had uncles, older cousins, as well as elders from the community who were to me as fathers in some respects. But the two that were most influential were my biological father, Edwin, and my stepfather, Vincent. Both were polar opposites of one another.

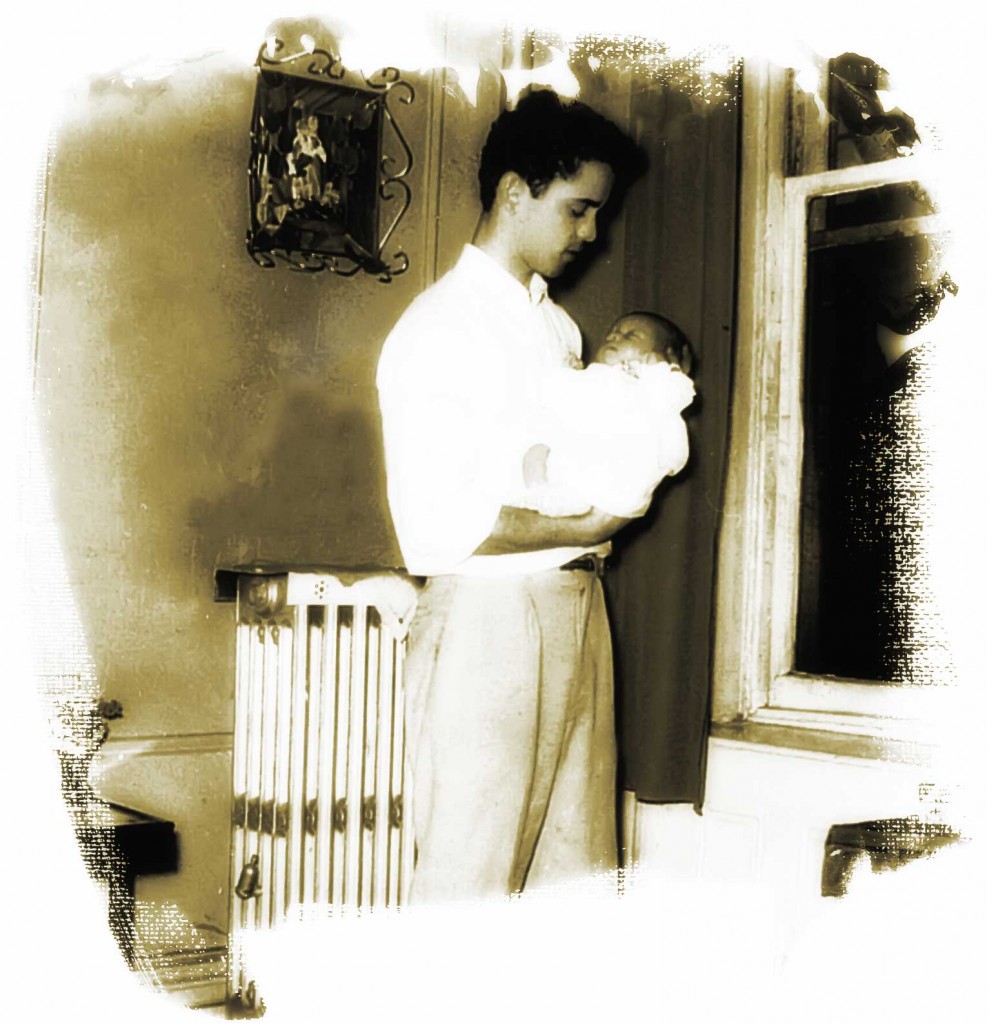

My father was almost all yang: penetrating intelligence, extroverted, creative, charismatic — he was everything a little boy wanted as a father. I adored him — worshiped the very ground he walked and I wanted to be just like him. My father passed on to me the gift of the thirst for knowledge and I could never repay him for that. My father’s example taught me that there was a higher purpose in life and he taught me love for knowledge, beauty, and truth.

My stepfather, Vincent, was almost all yin — he was easy-going, definitely not cerebral, loved doing things with his hands, and loved music. As a child he would take me to his various jobs and brag to his friends and co-workers that I was a genius. Then he would tell his co-workers something like, “Go ahead, ask him anything,” and they would and I would almost always get the answer right. He used to get a big kick out of that. Vincent, instead of resenting my intelligence, supported it. Any other man would’ve felt insecure, but not Vincent, because he was easy going almost to a fault. Not that he was a pushover, he wasn’t, he had the hands of a carpenter, large and rough, and I had seen him knockout a much larger man with one punch. He was just less confrontational than my father. Vincent’s example taught me dependability, consistency, “showing up” as he used to put it.

These days it’s popular for talking heads and politicians of all stripes to go on at length about fathers and fatherhood. On one side, there’s the myopic notion that almost all social ills can be placed firmly on the shoulders of fathers — or “absent” fathers. Of course, this is just a form of scapegoating. Sure, fathers are important, but a father being more “present” doesn’t automatically translate to a better, more just society.

I once helped create a leadership development workshop that emphasized relationship-building skills. Leadership is about being able to connect to people, not forcefully leading them by the nose. Whenever I would ask workshop participants to list what they perceived as leadership qualities, nurturance — a core relationship- tool — was almost never mentioned. When our culture emphasizes breadwinning and individual success at the expense of caregiving, the welfare of our children is at risk. A father’s absence impacts the development of his children: development of social skills, self-esteem, and attitudes towards achievement. But how we define masculinity and gender roles, and essentially relegate men to a role defined by absence is quite telling: the father’s role is out there in the “real” world. More importantly, our culturally warped understanding of masculinity contributes to various forms of maladjustment, such as lack of impulse control, incompetence, dependence, and irresponsibility. The son of a psychologically absent father experiences a weakened identification with what it means to be a man, and the daughter of such a father experiences a weakened relationship to the masculine principle.

Yet, in the name of family financial and psychological welfare, our legal system emphasizes the importance of the father’s job, and therefore his absence, and award child custody to the mother nine times out of ten. When societal attitudes are discourage the father’s active nurturing involvement in the family, then we see the fragmentation of family relationships so common today.

Don’t misunderstand my point: I am not advocating for some misdirected notion of “men’s rights” at the expense of women and mothers. I am saying that we need to redefine what it means to be a man.

In the end, we are all flawed creatures. We all make mistakes. As for myself, I would say that if you were to ask my son, he would give at best a mixed review. More likely, I don’t think he would characterize me as a “good” father. And he has good reasons for his view. I guess I too am all too human. I guess what is important is not to get too stuck in who’s “wrong” and who’s “right,” but to do the right thing at the right time because it is the right thing to do at that moment.

And yet my own experience leaves me with the feeling that a good father requires more than getting the task done right. Perhaps fatherhood is more about being who you are and revealing that vulnerability to those you love. When I reflect on the relationships between fathers, sons, and daughters, I am reminded of the words of the poet Rumi: “Out beyond rightdoing and wrongdoing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there.” My son will one day be a father and if he can take even a little of what my own fathers/ mentors gave me, then he will be a man, for ultimately, it’s only men that can initiate boys into manhood.

My name is Eddie and I’m in recovery from civilization…

Thank you for sharing those beautiful words Eddie. “Perhaps fatherhood is more about being who you are and revealing that vulnerability to those you love.” I too appreciate all of those men (and women) in your life that helped to shape you into the person you are. Have a great Fathers Day.

When my children’s father died, i wasn’t very inspired to find a substitute father for them. Oh, i tried a few times, but i was looking for someone who would have the same values. As a couple, their father was the one who bestowed liberties, while i bestowed firmness. No decision was made without the children as the first consideration. We worked as a team, dividing the time for play, education and chores.

The problem with being a single mother was the number of men who felt the father figure the children needed had to be a strong disciplinarian figure. My children had been raised without corporal punishment, without forceful disciplines. I could make them wince just by telling them i was disappointed in their actions. I did not feel they needed a strong disciplinarian figure, just a kind man to help guide them.

They developed their own solutions. Using their grandfather as the measuring stick, they adopted their own father figures among my married friends. Although the personalities of the figures they chose were different; they were alike in one respect. The father figures they chose put the welfare of the child first. That’s all that can really be expected of any father; or mother.