Yesterday being veterans Day, I was reminded of the following. I wrote this right after my tio (uncle) passed away a couple of years ago. This story is based on true events. Some of the details have been changed, but the story is true…

What Really Matters, pt. 1: Tio Jaime

If we evolved a race of Isaac Newtons, that would not be progress. For the price Newton had to pay for being a supreme intellect was that he was incapable of friendship, love, fatherhood, and many other desirable things. As a man he was a failure; as a monster he was superb.

— Aldous Huxley (1894–1963)

“Cpl. Jaime Rosario, present arms!”

… silence

“Cpl. Jaime Rosario, present arms!”

… silence

“Cpl. Jaime Rosario, present arms!”

… silence

There is a faint sound, barely audible, and I realize it’s Taps playing in the background. I don’t know where it’s coming from, it’s barely distinguishable. It’s a crisp, clear November morning and each time my cousin’s husband, a member of the US Army, barks out, “Cpl. Jaime Rosario, present arms!” (or something like that), the ensuing silence is like a knife into my heart. The shock reverberates through me like a shot in the dark of night and my tears well in eyes before rolling down my cheeks.

It breaks my heart…

It’s Christmas morning early 1960s in New York’s infamous Lower East Side. My three cousins, Edgar, Miriam, and Jenny are young children and they’re crying because there are no gifts under the tree for them. They are crying not because they didn’t receive gifts, but because they thought they had done something wrong for not getting any gifts at all. There is no heat in the apartment; it’s cold, and the oven is on full blast, hardly making the kitchen bearable. Water is boiling on the stove. My aunt Sylvia cries silently, not knowing what to tell her children.

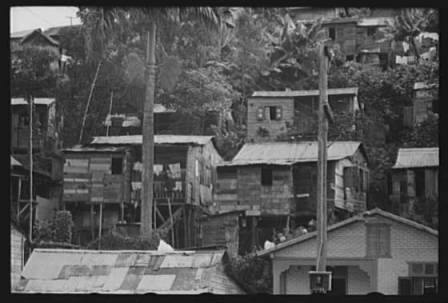

We all lived in the same building on the Lower East Side: 704 E. 5th St. I liked to joke that if a bomb had been dropped on “704,” the Rosario’s would have ceased to exist because most of us lived in that tenement building. I was only half kidding. It was a rat-infested building — a cold water flat — and the bathtub was situated in the kitchen. It wasn’t uncommon to be eating dinner while a family member bathed. The apartment had no toilet; we had to share one down the hall with the apartment across from us. The owners were derelict in all their duties except one: they were prompt in collecting the rent.

Too many of us lived in that two-bedroom apartment. Togetherness in those days was a little different: having your own “space” wasn’t an option. We were working poor, children of first generation Puerto Ricans, factory and garment industry workers, janitors, washerwomen. There was just one TV, owned by my uncle, Jaime, and all the children would all gather at his apartment to watch King Family Christmas Specials on this HUGE monstrosity of a TV that had maybe a 9-inch screen. Togetherness was different in those days: it was cold and huddling together on my uncle’s big bed was also about keeping each other warm. To have your own space in those days meant you froze your culo off.

Tio Jaime bursts into my aunt’s apartment and yells out, “Why is everybody crying?” My cousins, through the gaps in their sobbing tell Tio that they didn’t get any gifts and they don’t know why because they had been good. My uncle looks around, and in his unique comical way, he opens his eyes in wide exaggeration and yells out, “Aha! Here is the problem!” Pointing to the closed, securely latched window by the fire escape, he explains that the reason Santa Claus didn’t leave any gifts was because that, “Sangana mother of yours forgot to unlock the window and he couldn’t get in! C’mon! He left your gifts at my place and told me to make sure I came and got you.”

We never knew until many years later what Tio did — not until we became older and understood what had happened. Unable to bear the sadness of his nieces and nephews, he sacrificed so that everyone would have at least a little something for Christmas. Many years later, my cousin Cynthia, Tio Jamie’s daughter, would joke that her Barbie died of starvation that year because they gave Miriam the Barbie Oven — you know those ovens with the light bulb inside that let you bake muffins and stuff like that?

We could never really thank Tio because he hated for these acts to be known. For him, it wasn’t being valorous or a committing a good deed, it was what had to be done — nothing extra, he liked to say. He did this many times, more than we will ever know.

Togetherness was different in those days, I think, because to have your own space meant your loved one would not receive a simple Christmas gift. It wasn’t an option…

Many years later, as a university student, I began a preliminary study on fatherhood within the Puerto Rican context and what I read in the research literature troubled me because it didn’t jibe with my own experience growing up Puerto Rican in New York City. While it was true that my own father was often absent, I also had the luxury of surrogate fathers like Tio Jaime who offered a conscientious model of masculinity.

“Cpl. Jaime Rosario, present arms!

… silence

By now, my cousin’s husband’s voice is cracking with emotion and he too is crying because there is no answer. My heart breaks open and it seems that there’s a hole in my life and the crisp November wind blows through it mercilessly.

It breaks my heart…

My uncle served in the military and was part of that famous Puerto Rican unit, the 65th Infantry Regiment (also known as The Borinqueneers).

A Company, 1st Battalion…

Tio never talked about his service, but my cousin’s husband discovered that he participated the famous landing at Inchon, Korea to free surrounded US Troops. His unit received the Presidential Unit citation, The Meritorious Unit Commendation, and two Republic of Korea Unit Citations. My uncle detested violence and he was wounded during the war for which he received the Purple Heart Medal.

But that wasn’t what Tio was about. I’ll always remember Tio Jaime for his raunchy sense of humor. He was like the Puerto Rican Sid Caesar — he was hilarious. He always had a good joke that would make you laugh from the belly. He was more about humor and facing life’s hardships with a laugh. Smiling in the face of adversity is how I will always remember Tio, forever thanking him for that gift.

“Cpl. Jaime Rosario, present arms!”

… silence

Love,

Eddie

“Unable to bear the sadness of his nieces and nephews, he sacrificed so that everyone would have at least a little something for Christmas. ” Very moving, you brought him to life again with your words. Thank you.

Now you must tell me (because I am a little dense) what it was that he did; what was his sacrifice to get the kids presents?

” Smiling in the face of adversity is how I will always remember Tio, forever thanking him for that gift.”

A beautiful tribute.

Excellent writing, Eddie! Thank you.

I also found the story very touching. Having spent my childhood in a very harsh and minimal existence, it is easy for me to imagine the type of sacrifice Tio Jaime had to make in order to provide his nephews and nieces with Christmas. We may be separated by differences in rural and urban life styles, but in our experiences with positive characters determined to overcome their hardships, i think not so very different at all. You grace your work with a very literate style.

@Benni: Good question! It’s the type of question that makes writing better. Part of writing in the “blog style” (which has dominated much of my writing these past few years) is that it has served to cut my writing short. My challenge is to be able to get a point qa cross within on one-page MS word page (12 pt. times new roman). In many ways, this isn’t good.

At the time, my uncle was a factory worker making very little money, working long hours. I assumed he made sacrifices because he barely made enough to survive. I remember, for example, his having to go to the emergency room after one winter storm because he had frostbite. His boots had holes in them. I gather that that old ratty coat we would secretly make fun of was because he made the choice of having his wife patch it up rather than buying a new one.

@Saynt and Mitchell: Thanks. If any of you get a chance, check out the link to the documentary about the “Borinqueneers.” It’s a little-known story. I tried to convince my uncle to agree to be interviewed for the documentary, but, as was typical of him, he didn’t want the exposure. He always felt war and violence was completely, utterly wrong.

@Karlsie: I couldn’t agree more. Shared adversity (when it is perceived as SHARED) is the greatest community organizer in the world. This is why I believe that, as more people are thrown into the maws of the Beast, the greater the potential for all of us, regardless of culture and race, to come together.

What a lovely man. You are so good at making the people you love real for your readers. I thank you for all of the stories you share.

This is a story I know well too and you are correct it doesn’t matter if we are urban, rural or somewhere inbetween. If we have lived even a little of this we KNOW. And hopefully we don’t try to forget, that is the greatest saddness to me, people who forget where they came from, the paths and the people who brought them there.

Your Tio, what a man!

[…] [Editor’s Note: Do checkout Eddie’s latest article over at subversify.com] […]