I had just dropped off to sleep when there came this terrific knocking on the front door.

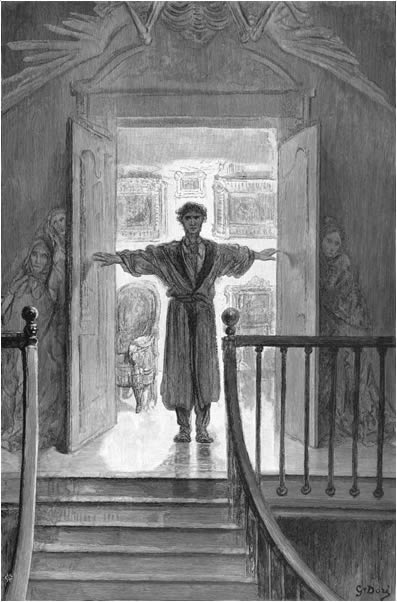

Cursing, I got out of bed and went downstairs to the door. The knocks were so loud that the door was threatening to break from its mounting, and I just managed to get it open in time. I agree I wasn’t thinking too clearly – the proper response when someone bashes at your door in the middle of the night is possibly not to throw it wide open for them.

But, anyway, that’s what happened. My concern was at the moment for my door; doors are expensive; and hiding under the bed wouldn’t have stopped whoever it was from breaking it down anyway.

So I threw open the door a millisecond before it would have disintegrated and goggled at the knight in chain mail on my doorstep.

“I’m sorry if I disturbed you,” the knight said politely. “It’s just that I’m rather in a jam, and I’d appreciate a little help.”

“What kind of jam?” I asked, politely stepping aside to let him in. At moments like this one I tend to act in some ways like an automaton, even if my heart feels like it’s going to explode through my chest any moment.

“It’s a long story,” he said, stepping in and looking for a place to put his lance down. It was so long that he had to lean it against one corner of a wall and the tip reached the ceiling. I looked outside before closing the door, but there was no horse in the street.

“I thought you would have a horse,” I said, shutting the door. It felt a foolish remark, but evidently not to him. “Horses don’t get to heaven,” he muttered, dumping his shield with a clang on the floor.

“Heaven?” I picked up the shield – it was very heavy, so heavy that I staggered a little – and propped it against the wall. It had a heraldic emblem of a red cross on a white field. “What are you talking about?”

“I’ll get to that.” He walked over to the chairs, squeaking slightly at every step. “My damned armour is getting rusty,” he said. “Not that I’m surprised. I’m surprised at nothing any more.” Sighing, he sat on my most prized chair; an antique carved piece I’d bought at auction. With a splintering crash, the chair collapsed.

“Sorry about that,” he said, indifferently. “You can say what you want, but it was going to happen. Everything happens to me.”

“Look,” I said, carefully, “that chair was worth a great deal of money, so I think it’s something that happened to me as much as it did to you.”

“Ah, it would have collapsed anyway; it must have had dry rot or something – it was old enough. Besides” – he scrabbled in the wreckage and handed me a piece of paper – “this might be a treasure map or something.”

“But –“

“And anyway, your troubles are nothing compared to mine. All you’ve had is a broken chair. I’ve been kicked out from heaven,” he said, sitting on another chair. I held my breath, but this one held though it creaked horribly. Then I realised what he’d just said.

“You’ve been kicked out from heaven?”

“Are you deaf? That’s what I said, didn’t I? I’ve been kicked out from heaven, that’s what I said.”

“You’re telling me you’re dead?”

“No longer,” he muttered. “That’s just it. No longer.”

“Let me get this straight.” My head felt as though it was wobbling insecurely on my neck. “You came here from heaven? You’re dead?”

“I think I told you I wasn’t dead any longer.” Now he sounded distinctly miffed. “I don’t know why you can’t understand simple things I tell you.”

I gulped. “Why have you been kicked out from heaven?” It seemed to be the best way of humouring this lunatic.

“Ah, there’s the rub.” He removed the heavy helmet he wore and rubbed his face. It was heavily bearded and he had longish greying hair. His face was pale and deeply lined, his eyes set so far back in their sockets that they merely emitted a grey glitter. And only now did I realise something else – I could see him clearly, even though I had, in my hurry, forgotten to turn on any lights. And with this realisation a faint foreshadowing of fear came on my soul.

“Ah, there’s the rub,” he repeated, rubbing away. “I was in heaven a good long time; eight hundred years, a thousand, something like that. All very nice, if you like things that way.”

“You didn’t?”

“Don’t interrupt. Heaven’s all right, as I was saying, but it’s deadly dull. Not a single tournament or skirmish, not even a decent drinking session or game of dice. But you learn early on to keep your thoughts to yourself, so you don’t get into trouble.” He paused and began rubbing his beard.

“I said, didn’t I, that I’d been in heaven a good long time? Well, I was there ever since I died in one of those Crusades – I don’t rightly remember which. Anyway, I had a high old time in those years, killing the infidels, burning their homes, raping their women, and selling their children into slavery. All that was all right, you know; and by special blessings of the Pope and all, we went right to heaven because we’d done a great and good thing.

“And now yesterday –“ his beard shook with emotion as much as rubbing “– they tell me that all that’s now officially declared evil and so I’m a sinner and I’ve to get out of heaven, after all these years and all.” He bent his head on his hands and began to sob. “After all these years!” he blubbered.

I made as if to pat him on the shoulder, but thought better of it. His shoulders were thick with chain mail and surcoat. He’d never have felt my pat. “So,” I said, “they told you to leave heaven. Then what? I mean, what did they tell you to do, become a ghost or something?”

“No, no, it’s far worse than that.” He raised his grey shining eyes to mine. “I protested. They told me to go to hell.”

“Hell?” I looked around. “Hell, I mean, I know this isn’t much, but for all that – well, it isn’t hell.”

“Isn’t it?” he said darkly. “If you really think about it, the way you all live…but anyway, they didn’t tell me to go straight to hell. That’s something, isn’t it?”

“Depends,” I said cautiously, waiting for what was coming next.

“No,” he went on, as though I hadn’t spoken. “They told me to take a night’s detour through earth. They said I could be alive that long – and if I could do something that still counted as a good deed, they’d consider re-admitting me to heaven.”

“Just you, alone?”

“How should I know? There were thousands of us on those Crusades. But how does it matter to me what happens to others? I’m I, after all.”

“So you’re here to do a good deed, and you want me to help you? Is that it?”

“That’s it,” he said, looking almost pathetically grateful. “That’s just it.”

“Well,” I said slowly, “if you’ll pardon me for asking – why pick on me?”

“Why not pick on you? Your door was right in front of me when I arrived. Whom should I pick on otherwise, the King of Sweden?”

“All right. Let me think.” Under normal conditions, in broad daylight besides, I might have possibly had a doubt or two regarding his account. I don’t really know why I believed him. Maybe because this was the dead of night and conditions were far from normal. Maybe because he was armed and armoured and I was in shorts and a sleeveless T shirt. Maybe because he just looked like he was telling the truth – and then there were the glowing eyes and the fact that I could see him clearly in the dark. “You’re here only for the night?”

“Just for tonight, and half of that’s over,” he said hoarsely, leaning towards me. His halitosis made me recoil. “You know, I have a sneaking suspicion they won’t even wait until dawn. They’ll just pull the plug at any moment and say the night’s ended in some part of the world. So…”

“So, really, you haven’t any time.” I stood up and paced back and forth in the darkness, past the wrecked chair. “What do you want me to do to help?”

“You haven’t any problems I could set right, do you?”

“No,” I assured him, and then added, “none that can be put right in a night, anyway. Troubles I have plenty of, but not the sort you can help solve.”

“Try me,” he said, his grey eyes glowing in their pits with pathetic desperation. “Please, try me.”

So I told him a few of them. He blenched.

“No, I see what you mean,” he said. “You really can’t think of any little problem you have for me to put right?”

“Listen,” I said slowly, “you did say heaven was deadly dull. Who knows? Hell might be a better place.”

“I’d rather not take the chance,” he said. “I mean, I’m used to heaven and all.”

I can’t really say why it seemed important that I help him – it just did. So I paced back and forth some more, and thought – thought hard. Ultimately I went upstairs and got my cell-phone. With a sigh of relief, I found that her phone number was still on it. I was afraid I’d deleted it.

She was still up, of course. She had always been a queen of the night. “It’s going to cost you,” she said when I’d explained the situation. “I mean, this is really going to cost you.”

“I was afraid of that,” I said unhappily. “How much?”

She laughed her rich husky hooker’s laugh. “You’d turn white if I put a price on it, so I won’t. But I’ll want some favours. Big favours. Huge. I’ll call them in when the time comes.”

“Listen,” I said desperately, “I’m not asking for any bloodshed or anything, you understand? It’s not as though anyone’s going to die.”

“Except your mad friend who thinks he’s been kicked out of heaven?”

“Except him,” I agreed. “But he’ll re-die, not die, and it’s his lookout.”

“Just tell me this,” she asked then, slowly, “why are you doing this for him? Just what is in it for you?”

“Nothing,” I informed her. “Nothing at all. I just feel sorry for the bugger. And also,” I added as a crash sounded from downstairs, the sound evidently of the creaking chair finally giving up the struggle, “I need him to stop smashing my place up.”

“Okay,” she said. “It’s your lookout. I’ll play my part – for now.”

I went back downstairs, slipping the cell phone, now in silent mode, into the pocket of my shorts. The knight was prodding a third chair, apparently testing it for strength. “Look here, Sir Knight, I have an idea. Chivalry is still good currency in heaven, I assume?”

“Chivalry?” he asked, turning slowly, his face uncomprehending. “What’s that?”

“You know – suppose you saved a damsel from rape or something. That would count?”

“It would depend on whether she was a good Christian,” he said, turning back to the chair. “If she is, then that’s fine. If she isn’t…”

I thought back to my – uh, friend’s – throaty chuckle. “I can assure you,” I said, “that she’s not a veiled Saracen infidel. Not by any stretch of the imagination.”

“All right,” said the knight, and stood up. “She’s in trouble, is she?”

“Yes,” I told him, and calculated how long it would take for my friend to set up the scene. “You’d better get going soon,” I said. “She’s just prayed to the Lord that she’s in desperate trouble, and the Lord told me about it…” I wondered if he would swallow this rubbish; he did. I then felt a brief vibration in my pocket. “In fact, the Lord says that you’re the only one who can save her.”

“Where is she? And what is the trouble?”

“It’s a bit of a way,” I told him. “We’ll have to take my car, since you have no horse. As for the trouble – you’ll find out when you get there…”

Of the entire episode, that car ride was the strangest. The knight’s immense lance was sticking out of the rear window, his shield and helmet clanging together in the back seat, while he held tight to his side of the dashboard with sheer terror as I drove through the utterly deserted streets. If anyone saw us, I didn’t see them. Maybe they were too drunk to care anyway.

“Relax,” I told the knight, afraid he’d carve holes in my dash; but he didn’t stop his tooth-clenched muttering. I realised he was praying.

From my house I drove right across town to one of those narrow mazes of lanes where any but the residents would be utterly lost. In fact, I was an old resident, which is why I knew precisely where I was going. My friend was a former resident too – and for a little time tonight, she, like I, would be a resident again.

I stopped near a dark old building from which a strong smell of something oily and greasy came. Across the street was the old church she had mentioned. It was dark, small, and deserted.

“It’s time,” I said, and got out to open his door. His relief at stopping was so great that he almost fell out, and would have had the door not been slightly too small to comfortably allow him and his armour. He stood near the car and shivered. I fetched his lance and his shield and helmet, one by one, and gave them to him.

“Where is this lady?” he asked.

“She’ll be right along,” I said. “You begin walking that way.” I pointed.

“Aren’t you coming?”

“You want this good deed to go to your credit only, don’t you? What good would it do to share it with me?”

He nodded and shambled off, uncomplaining. Again, I was struck by his extreme gullibility, but I had no time to dwell on that. I fished out my cell phone and hit the right buttons.

“Where is your friend?” she asked at once. “I’m scared. You know these are real crooks here.”

“Have they noticed you yet?” I asked soothingly.

“I’m nearly sure I’m being followed.” The edge in her voice was clear. “I should never have let you talk me into this.”

I watched the knight, still visible now because of his little glow of light. “He’s coming,” I said. “He’ll be with you in a few minutes.”

“He’d better. And suppose he can’t handle them?”

“I’m there too, aren’t I?” I got back into the car and turned on the engine, keeping it in neutral. “I’ll be there so fast you won’t have a hair on your head touched.”

“It’s not the hair on my head I’m worried about.” She was about to say something more, but then I heard a scuffling noise, as of someone running, and a gasping scream. At the same time the knight broke into a lumbering trot, his lance under his armpit. I heard him yelling something, even as I trod on the accelerator and shoved the gearshift to first.

From where I was parked I had to make two separate turns to get to her, something I’d not quite planned on – they had charged her a bit further from the place, the mouth of a dark alley, I’d counted on. So it took me longer to reach her than I thought it would. So by the time I got there, it was all over. My friend was backed up against the wall while the knight pinned one attacker to a dumpster with his lance through the man’s jacket collar, while slapping another back and forth across the face with his free hand. A third attacker lay on the road, peacefully sleeping.

I got out of the car. The knight turned his glowing eyes to me. “Have I done it?” he asked.

“You’ve done it,” I affirmed.

“Thank you,” he said. If he smiled I couldn’t see it under his helmet. A moment later he had vanished, quite without any kind of fuss, like a soap bubble collapsing. He was simply gone.

“I suggest you go too,” I told the one who – released from the dumpster – stumbled forward and began vomiting. The slapped one had already taken to his heels. The sleeper kept sleeping.

“Told you we’d be in time,” I told my friend, helping her into the car. “Where are you parked?”

“He just vanished,” she kept repeating. “He just…went away.”

“You’re right,” I said. “I suppose he was telling the truth after all.”

An hour later, I got back into bed, telling myself I’d sort it all out in the morning. I thought the excitement would stop me sleeping. I was wrong. In five minutes I was sleeping the slumber of the utterly exhausted.

I hadn’t slept an hour when I was woken by a thunderous knocking.

I stumbled downstairs to the front door and threw it open just in time. Outside, one three-fingered hand raised to knock again, stood a one-legged, one armed man in a tattered kaffiyeh and half an explosive jacket.

“Salaam aleikum,” he greeted, pushing past me. “I’ve just been kicked out of Paradise because they suddenly decided suicide bombing was a sin, and I kind of need your help…”

Hahahahaha, very ironic tale, Bill. Great dialogue.

Good humorous story. No good deed goes unpunished.

Well at least the powers of heaven are being even handed kicking out Suicide Bombers and Knights alike.