By Karla Fetrow

The Magic of a Word

There are some words that capture your imagination immediately; that trigger the mind with want; even need. An indiscernible craving fills you for something not truly remembered, but desired. This was the way I felt the first time I heard the name, “Jucitan”. Pronounced “WHO-chi-tawn”, it sounded like the wind, whispering its secrets and like the ghosts of an ancient world mourning for a fable.

The first time I saw the name, Juchitan, it was broadcast across the top of a stark, black and white poster. Underneath the label was the portrait of a man with numerous hands covering his eyes, his ears, his mouth and strangling his throat. “Where is this town?” I asked my companion. “What is its significance.” He admitted, he didn’t know.

It was the third year following the peso crash. My translating job was gone. The American businesses that had utilized my services no longer wished to invest in Mexico. For awhile, we supported ourselves through buying perfumes in Mexico City and selling them in Puebla, along with the wire work handcrafts we made. At first, it was enough, but as the crash deepened, Puebla was no longer big enough, varied enough to keep us in business. Once everyone had bought a certain number of perfumes, bracelets and hand bags, there was no need to purchase more for awhile. We needed to find some new towns, some new clients, who would set aside a small part of their grocery money to feed their vanity. We began traveling.

Traveling often meant hitching a ride on the big trucks to save the cost of bus fare. We never knew where they’d drop us off, but if it was near any town at all, it would do. It didn’t matter to us; small town, big town; even villages had the potential to trade a meal and a place to sleep for a new necklace and pair of earrings. We had become nomadic, pushing south toward Guatemala until we ran out of merchandise, then returning to Mexico City to start the cycle again.

One day, who knows when as it was a day like any other, with a steaming sun flattening the tall grasses, and the cracked sky etching out palm trees in the distance, our driver, who hadn’t been very talkative the entire trip, suddenly pulled over. “This is as far as I’m going today,” he informed us. “It gets hot out here. Too hot. I’m going to take a nap and finish up tonight when the air is cooler.” We looked at each other uncomfortably as we opened the door. There was no one. No traffic, no gas stations, no thrown together shacks selling food and beverages, only a gravel turn off that dropped sharply out of sight. “If you take that gravel road down to the bottom of the hill, there’s a village,” he said helpfully. “You can probably find something to eat and a place to stay for the evening.”

That sounded appealing. Hunger, a constant companion, was currently clamoring for attention. We left our host, who was already climbing into the bed at the back of his cab, with a final gracias and adios, and shouldered our back packs. The walk was several kilometers, but the grade was easy. It turned and slipped gently, bit sharply into the sides of thick, moist earth, the prairie grass bending over and waving, casting glistening shadows over the trail. A flight of parakeets startled, their bright colored bellies shooting about like lighter than air pin balls.

The village was much like any other; small, wooden shacks or bamboo housing spread over a concrete foundation; the smell of fresh tortillas scorching the air, a cantina where a few worshipers crouched in fold up chairs around card tables stamped with “Corona” signs. A Brahma bull browsed casually nearby, tethered to a fence post. We skirted carefully around it and pulled up chairs at an empty table.

The proprietor had a large grin. “What will be your pleasure?” He asked, apparently already filled with pleasure at having two strangers patronize his establishment.

“A tecate and a coca cola for the senorita,” answered Victor. When the proprietor’s eyebrows shot questions in my direction, Victor added, “she is a little girl, yet. She still likes soda pop better than beer.”

While he hastened to comply, he murmured gently as he set down the bottles, “a soda pop in hot weather can feel good. There’s nothing wrong with that. Some people never do get around to much else, and there’s nothing wrong with that, either.”

We could see that he was settling down to visiting with us and asking some questions about the busy outside world heard only in rumors at his door, so Victor quickly took the time to ask him if there was anyplace we could get something to eat.

“As a matter of fact,” said the man, “my Isabella has some fresh beans and rice on the stove right now, along with a plate of hot empanadas.”

The menu sounded good and we ordered. As we replenished our diets, we fed the good senor’s own appetites for news, philosophies and discussion. The evening stole in with scarcely any notice beyond the refreshment of a cool breeze. We inquired about a place to sleep and the Senor offered his home for the evening.

We were happy to notice that his house was probably one of the best accommodations in town. It was made of bamboo, with large, paneless windows draped over with netting, a snug, thatch roof and concrete floor. There were various hammocks slung throughout the room he led us into, as though he was accustomed to having overnight guests. In the morning, after some more beans and rice, with a bowl of melon and pineapple thrown in for variety, Victor asked our host when the next bus arrived in the village. The senor shook his head. “No buses come here,” he explained. “But a truck comes through here every day to take people into Juchitan who want to do business.”

That name; dropping like a bulging bubble of water from a faucet; splashing with a clear, tinkling sound. Victor and I looked at each other in amazement, then he asked, clearing his throat, “you live close to Juchitan?”

“Why yes,” we were told, “it’s only about thirty kilometers away.”

Something stirred us deep inside. The ride, packed into the back of a truck with twenty other people on their way to the market, we scarcely remembered. The sensation was like that of traveling home after a long and wearying journey, realizing soon the bends and dips will carry you to familiar landmarks. Only there was nothing familiar about this journey, unless you counted the recesses of sub-conscious thought; that area that longs for what has not yet been articulated.

In the heat of day, the early afternoon, the plaza was barely alive. We approached a market woman selling candies and asked where we should sell. She shrugged. “Sell where you like,” she told us. “no one will bother you.”

That was some information well worth digesting. We had never heard of a town where street vendors weren’t bothered. We were always told, inevitably to move on or to battle for a spot in the local market. Cautiously, we explored the small park and decided to set up shop at its entrance. The market lady immediately came around to see what we were selling. “Jewelry!” She exclaimed excitedly. “You’ll do well. We all like jewelry here; and perfumes,” she added a little wistfully.

Victor promptly took an interest in the woman’s candies, then after buying some, offered her a discount on any of the perfumes. Her eyes snapped with pleasure as she blessed us then returned to her stand, cradling her new treasure.

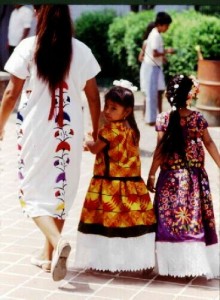

As the sun settled on the horizon, the town came to life. Juchitan is a lady of the evening, elegant and well-attired, in flowered dresses and hair piled high. Our initial amazement at being told we could sell unhindered, turned to astonishment at the crowds that gathered quickly and eagerly around our stand. In the middle of our success, the thong around us suddenly parted and a tall, incredibly beautiful, Spanish appearing woman stepped up to inspect our wares. Nobody spoke as she handed a basket she was carrying to a young girl who had been following her, and bent down to examine some earrings. They waited breathlessly as she opened a bottle of perfume and carefully sniffed its contents. She frowned a little as though puzzled. “American?” She ventured.

“The senorita brought them from the United States,” explained Victor, pointing at me.

“They have no alcohol.”

“The senorita says alcohol is bad for your skin. These are essential oils. You only need a drop or two.”

“I see. Does the senorita speak Spanish?”

“Si, hablo espanol,” i told her. I’m not often shy, but I always fall just a little bit in love with beautiful women, something that seemed to amuse Victor.

She smiled as though she understood the quick glimpse of admiration. “Underfed senorita, what else do you do beside carrying essential oils across the border?”

“I make earrings, necklaces, bracelets.” I pointed out the ones that were mine on the stand.

“You own your own business. You speak your own mind. You must be a Juchitan woman.”

While I pondered her remarks, she bought several items and handed them to yet another member of her entourage. “Do not stay at the hotels here in town,” she advised us. “They will charge you much and you will lose your profits. There is another hotel town the road about two kilometers from here where all the traveling sales people go. They will not rob you. They will ask reasonable rates. Knock at the gate and tell them Senora Alcazar has sent you.”

When she left, I noticed several young people fell in behind her, walking quietly and respectfully, carrying baskets of fruit, beverages, packages of food and merchandise. When she left, the real sales began. We stuffed our pockets so full of money, we were afraid of it falling out on the sidewalk. When we ended the evening, we had sold all the gold wire earrings we had made and half of the perfumes we had carried with us.

We were a little nervous about walking down the street with our expanded pockets, but nobody even turned and glanced at us. We hailed a taxi which took us to the hotel the Senora had advised us to visit, and knocked on the door. As the lady had said, the gate opened wide when we pronounced her name.

Our quarters were modest; a double bed in the middle of a tiled floor, with a small, painted table and two matching chairs, but the price of the accommodations was modest as well. Most of the tenants were sleeping in hammocks outside their rooms. It was insufferably hot, even with the ancient ceiling fan spinning lazily around. We wished we had hammocks as well. We opened the door, deciding we didn’t really need that much privacy.

During our first days in Juchitan, we didn’t really take much time to assess our surroundings other than noticing an enormous fondness for jewelry. Everyone wore it; children, teens, businessmen, market women, farmers and wives. We were even asked to make baby bracelets; specifically with red beads and amber, to ward off evil. I strung together half a dozen a day, and the mothers studied the patterns patiently, trying to decide which one would be the most effective against bad spirits.

It was only after a few visits between Mexico City and Juchitan, that we began to notice other subtle differences that made Juchitan society a little different than the norm. It began with Pacifico.

Pacifico was the hotel’s maid. While we were slowly noticing the strong family structure behind the hotel’s operation, Pacifico was noticing us. By our third visit, he had become bold. He would saunter into the room any time he noticed we were crafting jewelry, sit down on the bed beside us, try on several pieces, and generally bribe us out of a gift by promising us the cleanest, freshest sheets, which he rarely delivered.

My first thought concerning Pacifico was that he was the most badly spoiled maid I had ever seen. He skipped the rooms he didn’t want to clean. He spent long hours pouring over our beads when he was supposed to be laundering clothes. He hid from the Senora up on the roof when he thought she might send him on an errand. Sometimes, she would hunt him down, dragging him by the ear when she found him, scolding and telling him what a worthless servant he was, but she never would fire him.

I finally asked one day, when he had become so chummy he had started borrowing my blouses, how it was that the Senora put up with so much of his foolishness. “Don’t you know?” He asked, fluttering his eyelashes. “I’m special.”

This didn’t enlighten me. “How are you special?”

“Manita, isn’t it apparent? Somos hermanas.”

“You’re special because you’re gay?”

“Si. The Senora will never get rid of me. I bring her luck.”

We rarely saw the Senora at first, unless she was chasing down Pacifico. One day, this all changed. A scandal occurred on the upper floor when the Senora discovered her husband had been renting an apartment for free to a young prostitute in exchange for her favors. While the Senora chased the prostitute out into the yard with no more than the ragged ends of some clothing hastily thrown together in a shopping bag, Pacifico hid behind our door. He peaked out the window, obviously pleased that her husband’s ear was the one she was dragging about today instead of his. “You sit in the hammock and take care of the babies,” she scolded. “That’s all that you’re good for. I’ll run the hotel”

She plopped two small children into his lap, then hustled off, probably in search of Pacifico. The husband jiggled the babies a couple of times, secured them into one end of the hammock, then promptly fell asleep. “Isn’t the Senor the proprietor?” Whispered Victor.

“No,” said Pacifico, placing a finger to his lips and beckoning us to the far end of the room. “The Senora is. The men own nothing in Juchitan. Everything is run by the women.”

Later that day, the Senora invited me over for coffee. “You are an American, yes?” I nodded. “I am an American, too. I live in North America. That makes me an American.” She laughed as though she had told a good joke.

“You are different. You are from another country, but in many ways, you are not so different. You speak two languages, Spanish and English. So do I, Spanish and Zapotecan. You have learned a trade. I also have a trade. You have different customs. You cut your hair and wear men’s pants, but you follow rules. I too, have rules.” She nodded significantly toward the upstairs rooms.

“We are Zapoteca. We have been here before the Mayans, before the Aztecs. We are the first people.”

The Land of the Two-Headed God

The Zapoteca god of creation has two heads, one turned to the east, the other the west. One is feminine, the other masculine. In its four arms, it balances the planets, and rotates them around in a galaxy of stars. The upper torso has breasts, and the lower; thick, stout legs; both masculine and feminine. The child born both masculine and feminine is blessed because this child has the closest attributes to the duo-sexed god. The women are more blessed than the men, for the women understand the first growing spark of life and painful joy of giving birth.

“Among the Zapoteca, it is far more important to have baby girls than baby boys. The women have the most wisdom. They run the businesses, the schools and the homes. When a baby girl is born, the best of everything is given to her; the best food, the best clothes, the best education. The boys; what would you have done with them? They waste their gifts. They drink. They are careless with money. They get into foolish brawls. It’s better not to allow them too much.

“Each time a Juchitan woman makes a successful transaction; a new business deal, puts a child through school, marries off a daughter, improves her home, she buys a piece of gold jewelry to symbolize her success. You are a Juchitan woman and you should wear some gold now,” she advised. “If you do not wear gold the god of fortune will think you despise his gifts. ”

“How does Pacifico bring you luck?” I asked her.

“When a child is born a homosexual, he will never forsake his family. The other boys will run off and marry, maybe even forgetting to pay their respect, but the homosexual does not. He will always be there for his mother, his father, his unmarried sisters. How much luckier could a family be? Now, if a homosexual can bring his family so much luck, than by all practical purposes, a business can certainly profit from his presence. People will see him and think, ‘ah, this family is so clever and successful, they were able to afford the services of a homosexual,’ but as you can see, Pacifico is a very poor worker.”

“Then how can he be lucky? He is wasting your money for his wages.”

She smiled. “He brought you, didn’t he? He was once in the employ of Senora Alcazar and she sent you here. You wear boy’s pants and cut your hair like a boy, but you are not a boy. You are a senorita. You have a companion, but he is not your husband. You are foreign, and that will surely bring me luck.”

It was difficult to believe, in the marvelous new affluence Juchitan provided for us, that here was the center of revolution. The image of the strangled man slipped from our memories as we settled deeper and thicker into genial life of Juchitan society. Having left family to help family survive, we discovered a new family, a gentle family, covered with gold bangles and flowers. We slumbered peacefully in the rhythm of afternoon coffee with the Senora, small children playing by our doorstep, our evening sales prosperity, and Pacifico’s furtive visits. I introduced my best friend, a young Mayan girl named Lola. The Senora clucked worriedly over her. “You are too small,” she said. “Your family didn’t take care of you.”

“Everyone is small in my family,” protested Lola. “It’s the way we are.”

“Then you didn’t get enough to eat. You are Mayan. You should be taller, stronger. What has happened to your proud people?”

She didn’t say this as a question, but rather as a mournful, nostalgic statement. The Zapoteca memory is long and lingers beyond the transitory currents of recent history. It remembers what was, while painfully conscious of what is now. The Senora knew. Juchitan knew, while war rumbled and gossiped in the background.

The war came to us. We heard the first shots. It was late in the evening. We were in our quarters, stringing beads, preparing ourselves for the next day’s sales when the guns were fired. The hotel was immediately shut down, the gates closed, and everyone instructed to stay in their rooms. Victor, however, couldn’t stand the suspense. He bribed Pacifico to let him out so he could find out from the neighbors what was happening.

The ruling government in Mexico City had replaced Juchitan’s chamers of local government with their own members. The people of Juchitan were taking them back. During the next few weeks, we saw bloodshed in the streets, soldiers standing guard around the government offices, and nightly protests. One night, we were told to either pack our stand and return to the hotel, or join the protesters who were surrounding the zocalo. We joined the protesters. That night, the crowd threw rocks and bricks at the palace, and the rebels stormed the doors. The military was thrown out, and the favored representatives of Juchitan reinstated. “This is the way it always is,” explained Pacifico. “The government comes and takes over our offices, and we throw them out. They come again and again, but we throw them out. This is our war.”

The war spread. Rebels created road blocks and hijacked buses. Troops lined their tanks around the Capital City of Oaxaca. The seeds of discontent blew into the hot southern wind, settling in Mexico’s federal district, and blossomed. The war continues. It blows north, disguised under a hundred faces, a hundred excuses. It gnashes at the borders, using drugs to elevate its status, but it is most critically and essentially a war against a culture that calls itself the first people. It is a war against a two-headed god, both male and female, against an amazing society where women are dominant, where the men rarely work but will lay down their lives for their matriarch leadership, and where having a homosexual child is the greatest blessing the gods can bestow on a family. It is a war against beauty.

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Grainne Rhuad and Paul Bugnacki, LCSW, Subversify Team. Subversify Team said: In the loveliness of Juchitan the feminine blossoms~ http://subversify.com/2010/05/21/within-the-heart-of-revolution/ […]

Oh underfed senorita, I did not know thou couldst speak Espanol.

How I wish I could visit Latin America, just once.

Call me crazy, but I see nothing “beautiful” about either faction in this war – instead, all I see is one social establishment waging war on another. Since both societies in question judge the individual based on arbitrary criteria (such as gender or sexual orientation), I am equally appalled at both establishments: in my book, the supreme value (that gives all others any real meaning at all) is the sovereignty of the individual – not the collective or the gender or the sexual orientation and any social order that does not recognize that (most, in fact) I find worthy of revulsion.

As one who hates social repression of all kinds, I hope that the two-headed “god” dies along right along with all the others – leaving a “god”-less world of social anomie that the individual can assert his/her own will-to-power and fill that void with values of his/her own creation (not those of society).

The beauty in this story comes not from the re-occuring skirmishes but from the people. A people who have a place for everyone from the regal women to those blessed with differences. It is a place of honor that we rarely see provided in our western culture, this honoring of that which is different, strong, lovely and beautiful. I see even beauty in the men who take on a slower role, one that many westerners would consider feminine, but which is anything but.

No, to me this story is not about the conflict but about the people whose unsung songs exist withing the conflicts. The beauty is there.

Great job, Karla. This is a novel-caliber short story. Your at your best here, and shining in prose and viewpoint. Regardless of political ideology, this is a true-to-life episode that happened, that was experienced, and learned from. Perceptions form from our experiences. Yours is a voice that demands to be heard, and this is a culture that is thankfully, finally, getting some Subversify attention.

Si, Bill el carnecero, hablo espanol, but it’s been a long time since i’ve been to Mexico and i’m dreadfully out of practice. Mexico is easily my second most favorite place in the world, and the only reasons Alaska tops it is because Alaska is my homeland with its own cultural array of wonderful people and it has more wilderness. There is something about Mexico that makes you forget time exists. You become entrenched with a wonderful diversity of cultural distinctions and open minded philosophies rarely seen in the US melting pot, which has boiled so long, there is a taste of sameness in every bite instead of the wonderful bursts of flavor in lumps of carrots, potatoes and meat cooked just long enough to make them flavorful. Mexico absorbs without assimilating. There are Spanish towns in Mexico, Italian towns, French towns, Danish towns, indigenous towns, provincial towns that cling to centuries old traditions, ostentatious American colonies and the modern, International industrial complex of Mexico City. There are even towns absorbed in witchcraft and magic. They all add to the flavor.

Christopher, war is never beautiful, but the first attacks made were by the Mexican government against a very beautiful people. When the peso crashed, and the rest of Mexico went to its knees with millions of people out of work, millions of people homeless, while the elderly and small children died openly and daily in the street through starvation, Juchitan and its surrounding area was primarily unaffected. It had depended on and asked nothing of the government. The people lived simply, but lacked for none of their basic needs. The land is highly agricultural, supporting a variety of food products and the fishing is good. Their craftsmanship in weaving, embroidering and clothing manufacturing is considered the best in all Central America; even their hammocks are the finest. They mine and smelt their own gold, something i didn’t know until i had been there several years. The government only wished to intrude on the Zapoteca governing body to seize control of their natural resources.

The Zapotecan people survived the invasions of the Olmec, the Mayan, the Aztecs and the Spanish. Their two-headed god represents the balance between male and female. This thousands of years old society long ago favored women as their leading constituents as they believed women would handle their financial affairs with the most wisdom and would be the least likely to lead them into war. I have never heard a Zapoteca man complain about his matriarchal upbringing. In fact, i knew many who were elevated to high positions because of their intelligence, diligence and sense of fair play. The ones, like the Senor i illustrated, who had no great ambitions, were perfectly content to remain in their positions which left them like pampered, well-fed, well cared for housewives. You speak of individual choice, but what struck me was these men had individual choice yet still remained loyal to their matriarchal leanings.

It is a terrible thing to destroy a culture as each culture has its own beauty. The Zapotecan culture is the foundation from which all North American tribes sprang; most of which are matriarchal in their philosophy and social net-working; although to various degrees. My main reason for presenting this culture was to illustrate a people whose belief system is the exact opposite of the Western world’s largely patriarchal society which cannot even begin to imagine what it would be like to be born into a world where women and homosexuals were favored. In essence, the war against Juchitan is a war against the Native American people by the gimme, gimme culture of Capitalistic enterprise.

Grainne an Mitch, thank you for seeing the underlying soul of the story. Although i generally try to take an objective view, it becomes very difficult when i write about a people or culture i love. The Zapotecans taught me much in my search for my Native American roots. They are as important to Native American history as those Eastern nomadic men are to the believers of the Bible.

[quote=grainnerhuad]The beauty in this story comes not from the re-occuring skirmishes but from the people. A people who have a place for everyone from the regal women to those blessed with differences. It is a place of honor that we rarely see provided in our western culture, this honoring of that which is different, strong, lovely and beautiful. I see even beauty in the men who take on a slower role, one that many westerners would consider feminine, but which is anything but. [/quote]

I think you completely missed my point – I wasn’t referring to the skirmishes here (I personally find violence to be just another part of the animal world – and we *are* animals, after all…) but to the arbitrary designation of roles based on such things as gender or sexual orientation at all. Granted, the way they do it is rather novel (matriarchy) but that means nothing to some one who values the sovereignty of the individual above all else: I absolutely *hate* social orders that ascribe value to people based on such criteria – to me, the only society that has any rational basis for existence is a strict meritocracy (where no one is given any special privileges based on stupid things like what they are born with or what their personal preferences).

For those reasons, I find this society just as repulsive as a traditional Western patriarchy and I would happily see it die in a maelstrom of anomie (along with all other social establishments that don’t respect the sovereignty of the individual).

@Karlsie,

I got all that – I understand how these people have survived attempts at control from the feds, how they are proud of their heritage, the unconventional take on this artificial concept of male-female duality (it’s a load of crock – as the duality exists only as a social construct and only has power if people believe in it) and all that jazz. Of course, such things mean *very* little to me in and of themselves: in my book, the *only* attribute of merit is the relationship between the collective and individual – in other words, whether the collective recognizes the individual of sovereign or not (everything else is secondary – for *that* relationship gives all else meaning and value) and from what your story conveys the answer seems to be “no.”

If anything your article reminds me of why I hate human society in general so much – it seldom judges people on their capability or what they may be willing to contribute, but rather focuses on asinine traits like gender or sexual orientation (as evidenced here by denying males property and giving preference to homosexuals – if they practiced the reverse I’ll bet you would be crying “sexism” and “discrimination”).

I forget who once said it (it was either Lucretius or Seneca) but the quote goes as such “the dream of the slave is not freedom, but to own a slave of his own.” I can see why some one who is accustomed to living under the slavery of Western civilization would appreciate the slavery the people of Jucitan practice – it’s as though the slave under one social establishment suddenly became the master. If you love that type of slavery you can keep it: I say to hell with both forms of slavery – I’m going out to the country to wait for this disease called civilization to run its course and die.

Christopher, in all reality, i actually agree that “superiority” based on gender, race, nationality, or anything else that doesn’t reflect individual ability but rather a popular view is a crock of shit. However, considering that most of the world is so entrenched in patriarchal perceptions of how things are done they aren’t even aware when their thinking is entirely masculine influenced, i still feel it was appropriate to reveal the other side of the coin. In many supposedly emancipated Western countries, single women with children comprise the largest percentage of poverty stricken or low income families. The highest percentage of domestic violence is committed against women. While women are anxious to prove their abilities in what has been considered a man’s field of expertise for centuries, many have few ideas of how to present their perceptions without the emasculated view or by selling their sex. Hillary Clinton, Margaret Thatcher, Condelezza Rice; battle axes in a woman’s clothing. The super heroines of movies kick box, carry guns and murder. Even the campaign to bring women into literature is a weak dick; mediocre dialog, perceptions set from the view of the pampered, the spoiled, the condescending rich using a bleeding heart as their instrument. Give me a freakin’ break. These women couldn’t care less about her sisters in struggle or they would learn to struggle by their sides.

It’s time for women to recognize their true strengths, their true capabilities. They don’t have to mimic men. They don’t have to be their puppets. They do have to learn who they are as women, what they truly believe, the limits as well as the expertise of their abilities without the flim flam of physical appearances, the battle of the sexes to “prove” who’s best, and the bleeding heart syndrome to weep your way into the media spotlight.

Seeing the treatment of the Mayans when I went to the Yucatan was disturbing. The indigenous people of that area were treated worse than the Native Americans here were treated. Rather than a large reservation, they had a small acre. Even under those conditions, though, they continued to grind their corn with a smile on their face, though the smile may have been for the benefit of the tourists. The treatment of the animals was equally disturbing. There was a monkey kept on a short piece of thick twine that would choke him when he fell off the deck since his feet couldn’t reach the ground. I tried to speak with the owner, but to no avail.

Space Eagle, the Mayans received a very raw deal. Most of the tribes that live on the Yukatan Peninsula do not own the land they are living on, even though they have lived there for hundreds of years. They are “allowed” to stay there, but are not allowed to own more than a certain amount of livestock, grow more than a certain amount of food, or to acquire more than a few basic material possessions. Two or three times a year, the federales spread out through the villages, checking to see if any show signs of affluence such as new clothes, well stocked cupboards, televisions, refrigerators, etc.

Most of the indigenous villages are destitute, whether they own their land or not. They are the last to be hired, the last to receive services, the first to be signaled out and have their bags checked on the buses and trains. Because of their intense poverty, they have a very indifferent attitude about animals. All animals are potential food. It’s one of the things you learn to accept.

The Mayan girl i mentioned in the story had eight brothers. Two lived in Mexico City and one in Morelos. The entire family made handcrafts. Lola worked the street artist circuit, picking up goods the family had made, traveling from Yukatan, to Oaxaca, than on to Mexico City where she met with two of her brothers, traded goods, and transferred money to their safe home in Morelos. She was one of the lucky ones; striking to look at, highly intelligent, well educated and able to speak Spanish, Zapotecan and Italian, as well as read Mayan heiroglyphics. She told me the tales they spin to the tourist crowds concerning Mayan history and their pyramids were very inaccurate, a subject i might try and treat some day.

[…] Within The Heart Of Revolution Submitted on:Tuesday 1st of June 2010 02:27:40 PM voted by 5 users […]

Hello, I came to your blog and started reading along . I decided I would leave my first comment. I dont know what to say except that I have enjoyed reading the postings. Nice blog. I will keep visiting this blog very often…