“In truth, it was a gallant sight

To see a thousand men of might

With guns and cannons, day and night

Fight sixty crafty Indians”

— Anonymous; Yreka Journal (1873)

When the first white settlers came to the fertile valleys of western Oregon in the early 1850’s, one of the largest and most independent tribal constructs they would encounter were the Modocs.

The Modoc peoples had lived near and about their Great Lake (now called Tule Lake) since around 1650CE. They hunted, fished, and sometimes ate the wokus, or freshwater-lily bulbs which were plentiful on the shores of the lake.

Resenting encroachment by white settlers who brought cattle, fences, and measles to the region, the Modoc adopted a simple tactic – when their land was taken, they raided farmhouses. When their game was killed or stolen, they stole cattle in turn. When their people were shot for sport, they shot white settlers.

This did not sit well with the newcomers.

Ever-more-strident demands by the settlers to the fledgling state government in Oregon City, Oregon did not fall on deaf ears. The state raised the Oregon Volunteers, a citizen militia to deal with the Modocs and force them to a reservation which was set aside in the upper Klamath valley. Through this process, the 3,000-strong Modoc tribe was reduced to a shadow of themselves – some 300 people.

Schonchin, the Modoc chief, and Alfred Meacham, the superintendent for Indian affairs in Oregon, reached the reservation-accord in 1864. Under its terms, the Modoc would decamp for the northern part of the Klamath valley and attempt to live in harmony with the Klamath tribe, which had also been located there.

The Modoc attempted to build homes on the reservation land and make a life there. Continued mistreatment by the Klamath tribe (longstanding rivals of the Modoc) resulted in the Modoc making further attempts to relocate within the reservation. By 1865, they’d had enough.

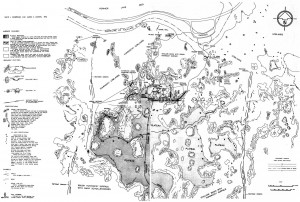

The Modoc left the reservation and returned to their homeland on Tule Lake, on the present-day border between Oregon and California. Part of this land contained significant lava beds, one which contained an extinct crater with caves in the sides and some collapsed lava tubes on its perimeter. The collapsed tubes formed near-perfect trench-lines in the rough shape of a square. Beyond the collapsed tubes were lava-fields nearly a mile long in all directions from the crater. Elevation from the base of the lava fields to the crater was not great – perhaps 150’ – but the natural ‘lava fortress’ could not have been better constructed if designed by military engineers; it provided four distinct fields-of-fire, a water supply at Tule Lake, and a natural corral for livestock, plus caves in which the women and children could take shelter.

The Modocs had long used this geographic feature, which they simply called “The Stronghold”, as a natural defense against other warlike tribes.

By this time, another Modoc leader, Kie-ent-poos, had assumed the mantle of chief from the aging Schonchin. He attempted to work with Meacham to enable the Modoc to attain separate tribal status and hence, their own reservation. This was recommended by Meacham in 1870.

Kie-ent-poos had beaten Meacham to the punch. He had already removed his people to their former home near Lost River. By that time, however, several dozen settlers had taken up residence in the ancestral home of the Modoc. Kie-ent-poos and his band harassed these settlers for over a year, attempting to force them off the land.

Further negotiations with the Modoc proved unfruitful, and in April of 1872, the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C. issued orders that the Modoc were to be removed to their former reservation in the upper Klamath valley, peacefully, if possible, but by force if not.

The stage was set for conflict.

(Ancestral Modoc stronghold; from 1870’s lithograph – Modocs under Kie-ent-poos depicted conducting defense.)

Far before it was a state, Oregon was a place of contrasts.

During their stay at Fort Clatsop at the mouth of the massive Columbia River, Lewis and Clark used one word over thirty times in their journal to describe the day – ‘Rain.’ West of the Cascade Range, rain is the Original Fact, and it was the rainfall and temperate climate in the fertile valleys which made northwestern Oregon a destination for so many settlers.

In the 1840’s, wagons left St. Louis, Missouri by the hundreds, many with crudely-painted slogans on the wagon-canvas, “Oregon, or Bust!” The Federal Government, anxious to have another non-slave state in the Federal Union, offered free land to anyone who made it to Oregon and who could make material ‘improvements’ (many times, that meant nothing more than a cabin) to the land they claimed. People who were sick of the cities; in trouble with the law; restless; or who just wanted to see the land made famous by both Thomas Jefferson and Lewis and Clark went west, following the map made by the Lewis and Clark expedition, then picking up the Columbia in the far interior near Shoshone country in present-day Idaho, following the Columbia as it passed through the Cascades and into the interior of the Willamette River valley.

Many headed south, finding the new agglomeration of shacks, houses, brothels and drinking establishments at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers not to their liking (while this would become a proper city in the 1850’s – at the flip of a coin, it was named “Portland” – and while there was a proper ‘city’ and future state capitol just to south at Oregon City – many still wanted solitude). These southern-sojourners founded small cities in the southern valley: Salem (a former resident of Massachusetts saw to the name); Eugene (named after its founder), and Corvallis (a frontier-English corruption of the phrase “Core of the Valley”).

(Tule Lake – Oregon/California border)

Several had heard of gold in the Applegate district in far southern Oregon – the city of Jacksonville, Oregon, became the center of gold mining activity in the 1850’s – for a time, more gold was pulled from the veins in and around Jacksonville than out of the big claims in northern California. Settlers came for the gold – and stayed for the climate, which, while more-arid than the northern part of the state, agriculture (particularly ranching) was more than possible.

In central Oregon, the contrasts between the western and southern part of the state are even more dramatic.

Oregon is volcanic country. The fertile valley farmland was created through volcanic eruptions over thousands of years, and in the central part of the state, large lava-fields cover the landscape. Dramatic canyons have been carved over milennia by rivers which eventually empty in to the Columbia to the north, and in the south-central part of the state – Modoc country – it’s possible to see small, lush, well-watered valleys with a mile or two of lava fields.

Trapped both by the lava which is just under the ground-level and by the natural sandstone formations nearby, Tule Lake and Klamath Lake are the major water-features of south-central Oregon. These lakes are home to large numbers of migrating birds, freshwater fish (some of which are endangered), and lush vegetation nearby, the reeds of which are useful for weaving durable mats which local Native American tribal peoples used both as flooring and walls for temporary shelters during the summer months.

(Lava bed – Southern Oregon)

Everywhere else, there was abundant game. Deer lived in the broken woodlands which dotted the region, and thrived on the berries, fruit and grasses which grew nearby. Hunting was a main occupation of the Modoc, who used everything the deer provided – bones for construction materials and tools; hides both for clothing and shelter; meat for food.

While it’s now known that the absence of rainfall and the nearness of bedrock-to-surface makes this a very fragile ecosystem, the settlers knew nothing of this. They ploughed the land, killed most of the game, began draining smaller lakes for more farmland – and in the process, destroyed the lifestyle of the local indigenous peoples.

In letters home, the settlers both praised the southern Oregon area and spoke of the sameness of things – one said, “There’s two seasons here – hot; and cold.” Another marveled at the fact that perfectly workable farmland could be next to “…an ocean of rock….”, as the lava-beds were described.

In the spring of 1872, the Modocs had quit the reservation system for good. Kie-ent-poos led his people to a place called Lost River, not far from Tule Lake and their ancestral home, where they took up residence. Spring turned to summer, and finally to fall, as the Superintendent for Indian Affairs, Alfred Meacham, attempted to get the U.S. government to allow the Modocs to stay on their ancestral land. In November, with civilian/settler complaints mounting, Meacham was replaced by Thomas Odeneal, who shared none of Meacham’s enlightenment or behavior toward the Modocs.

Odeneal wasted no time in making his presence felt. He ordered Major John Green of the U.S. Cavalry to round up Kie-ent-poos and his band, “…peacefully, if possible; by force if you must….”, and return them to the reservation in the upper Klamath valley. To that end, Green sent Co. B of the 1st Cavalry to Lost River.

(Modoc Stronghold map — from 1873 survey. Note interlocking tubes on plateau – a natural fortress)

Fighting a delaying action, Kie-ent-poos lost one of his men to gunfire, killed one cavalry soldier, and gave his band of around 300 people time to break camp and evacuate to the Stronghold, the Modoc’s ancestral place of defense near both Tule and Klamath Lakes. The Battle of Lost River was over, and the U.S. Cavalry had been dealt, while not a major defeat, a taste of what was to come.

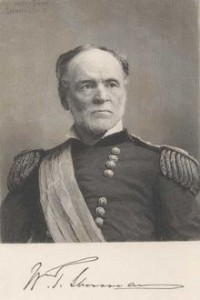

By this time, the Modoc issue had been elevated to the highest levels of the War Department. William Tecumseh Sherman, by then the commanding-general of the U.S. Army, personally ordered the Department of the Columbia (then possessed of around 1,500 officers, men, supporting personnel and other ranks), to move on southern Oregon and crush the rebellion. President Grant was apprised of the situation and approved Sherman’s order.

The 400-odd soldiers and volunteers under Lt. Colonel Frank Wheaton had every reason to believe that they would be successful within the week. Outnumbering the Modocs by 8 to 1, they deployed from the railhead near Klamath Falls to an area just to the west of Tule Lake.

(General W.T. Sherman – 1870’s)

Marching in the cold didn’t harm their morale – these troops had seen no action, and were, in the words of Lt. Colonel Wheaton, “Rarin’ to go!”Arriving in the early part of January, 1873, Wheaton encamped his men and began planning his assault.

Standard issue Army boots were the first thing Wheaton ordered from the commissariat in Portland – over 1,200 of them. The lifespan of an Army boot, not designed for use on lava, was about a week. Keeping his men drilled in that climate and environment proved daunting, as well.

In the meantime, the Modoc had rounded up or rustled all of the available cattle, and had them in the Stronghold’s natural corral (a large collapsed lava tube). They had brought several month’s worth of supplies with them. All they needed to do was wait.

On January 17th, 1873, Wheaton attacked with 400 men.

Marching up the slope in a light fog, the Army troops shredded their boots within the first hundred yards of marching. The Stronghold itself, a 150m/diameter lava-plateau with interlocking collapsed lava tubes serving as natural trenchlines, was the inner-defense which the Modocs would use after luring the Federal troops in past a series of outposts (snipers, placed in small collapsed lava-domes about fifty yards from the trenchlines).

Kie-ent-poos allowed the Federal troops – now with bloody feet after traversing 250 yards toward the Stronghold’s plateau – to get within fifty yards of the outposts.

Orange flame stabbed out from the rocks as Modocs began shooting Federal troops as they emerged from the fog near their outposts. Soon, the reek of blood joined the smell of cordite from Federal and volunteer panic-fire, as well as the sulfurous smell of the lava fields; Wheaton’s men managed to retreat back to their camp, leaving 37 dead and three wounded to the mercies of the Modocs.

Three shots rang out over the next forty minutes from Modoc outposts – their snipers were killing the wounded. Modoc war-cries were heard on the lava-slope; they were looting the bodies.

Now, every Modoc who wanted one had a U.S-Army issued Springfield breech-loading rifle, and all the ammunition he’d need. The short-range Winchester lever-action rifles with their smallish 30-caliber ammunition could now be relegated to outpost-duty.

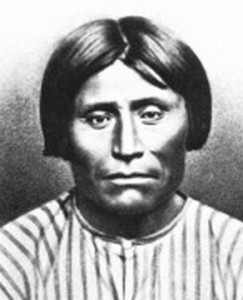

(Modoc warrior with Army-issue rifle)

The First Battle of the Stronghold was over.What had happened was considered impossible, from Wheaton up to the highest levels of command in Washington – precisely fifty-three Modocs had bested an entire U.S. Army column of 400 men, inflicting 10% casualties and losing nearly an infantry-company’s worth of rifles, ammunition, and other equipment.

Wheaton was immediately replaced by Colonel Alven Gillem of the 1st Cavalry. Kie-ent-poos continued to pull water, freshwater clams, fish, and wokus from the lakes, and consolidate his position.

The Modocs suffered no casualties.

Looking around their camp, Federal troops could not believe their eyes.

This was not the Oregon about which they had read. Dead grass; scrub; sagebrush – the land itself scabby with outcroppings of lava. One soldier wrote home to his family, “This ain’t the Oregon we thought it was”, he began, after remarking on the unique sulfurous smell of the lava-beds. “This place is Hell – Hell, with the fire out.”

Hearing of the defeat of Wheaton, Grant immediately did two things; he ordered General Canby, commander of the Department of the Columbia, to the Tule Lake encampment to sort things out, and he ordered the establishment of a peace-commission to attempt the peaceful resolution of the Modoc crisis, with Canby holding a pivotal role in this commission. (Alfred Meacham, the former commissioner for Indian Affairs, was to head the commission. Odeneal, the new commissioner, was not a part of the peace commission).

(Gillem’s Camp – Modoc War)

Further, through his old friend and commander of the U.S. Army, General William Tecumseh Sherman, Grant ordered an additional 1,000 troops sent to the lava beds immediately in order to begin a siege.

Grant’s intent was that this crisis would be resolved, one way or another, by the end of spring; 1873.

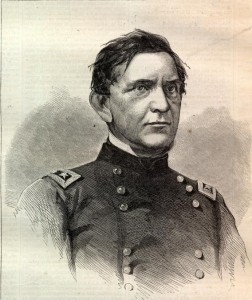

(General Edward Canby – photo taken ca. 1865)

Colonel Gillem, for his part, immediately began a strategy of ‘gradual compression’ of the Modoc stronghold. By this time, Kie-ent-poos had supplies for six months, and a constant water supply. Gillem intended to reduce the Modoc’s ability to wage war by cutting off the Modocs and forcing them to rely completely on their stored provisions. Retaining 370 men in the original camp to the west of the stronghold, he also ordered a Captain Mason to take 350 men to the east of the stronghold near a natural feature called Hospital Rock.

In the meantime, preparations were underway to encourage the Modocs to negotiate a peaceful return to the upper Klamath reservation. In order to pressure the Modocs to the peace table, General Canby ordered Colonel Gillem to move his encampment within three miles of the Stronghold. This was accomplished by April 1st, 1873.

In the Modoc stronghold, there was dissention.

Kie-ent-poos’ council, consisting of Schonchin John (the son of the former chief, Schonchin); Scarface Charley, Hooker Jim, Boston Charley and Curly-Headed Doctor all counseled that Kie-ent-poos attack the peace commissioners and in so doing, destroy the morale of the Federal government and its representatives, forcing them to leave the Modocs alone.

This naïve thought-process was resisted by Kie-ent-poos, who had seen much of what the U.S. government was capable. He argued that the resolve of the U.S. government would not be broken by attacking members of their peace commission, and that the result would likely be quite the opposite.

Scarface Charley put a woman’s shawl on Kie-ent-poos and began mocking him as a woman for his desire to make peace with the U.S. government and its troops. Under this pressure, Kie-ent-poos made the fateful decision to go along with the ambush of the peace commission during a meeting scheduled for April 11th, 1873, at a ‘peace tent’ halfway between Gillem’s camp and the Modoc stronghold.

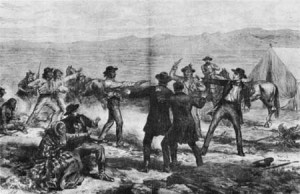

(Assassination of General Canby – April 11th, 1873)

This meeting – the first between a general officer of the U.S. Army and a native American chief during the Indian Wars – was to have a tragic outcome.

On April 11th, the commissioners, along with General Canby and two interpreters, arrived at the tent in the morning hours to find Kie-ent-poos, Scarface Charley, Boston Charley, and Curley-Headed-Doctor waiting for them.

Kie-ent-poos began by requesting that they be left alone on their ancestral land, and that the Federal government grant them amnesty for what had happened before during their resistance of Federal authority.

Canby countered by stating, as he had during prior meetings, that the Modocs lay down their weapons, and trust the Federals to protect them and look after them.

Signaling the others, Kie-ent-poos drew a revolver from under his overgarment and shot General Canby at point-blank range in the face. Schonchin John severely wounded the Indian Affairs commissioner, Meacham, while Boston Charley shot and killed another peace-commissioner, a Reverend Thomas. The rest fled, managing to evade the rifle-fire of the other Modocs.

The result was predictable.

(Coehorn mortar and caisson)

In February, Gillem had ordered two howitzers and five Coehorn mortars from the Presidio in San Francisco. These had arrived in late March, and were already deployed within range of the stronghold.

Already realizing that the flat-firing howitzers (a form of cannon) would not be effective against the rock-formations of the stronghold, he ordered the mortars (a device which fired an exploding-projectile at a 45-degree angle; which projectile was intended to explode over the heads of the defenders) brought forward and deployed in a manner which would enable them to drop their shells well-inside and over the stronghold.

Gillem’s gun-lines were laid-in and ready by April 1st. He awaited the results of the peace-commission, which he received in the form of echoed gunfire from the peace-tent on April 11th.

A courier relayed the news by horseback – General Canby was dead. Meacham was severely wounded, and wouldn’t live the day out without immediate care. Thomas was dead.

Gillem immediately wired Washington for instructions.

Kie-ent-poos and his band rode hard for the stronghold. While Schonchin John and Scarface Charley bragged to the others, Kie-ent-poos began deploying the other men to preselected positions to deal with what he knew was coming.

Gillem, to the west of the stronghold, decided to wait and coordinate a proper assault.

He ordered fresh rations and ammunition brought up, and the last of the men deployed. The volunteers had long since departed, leaving when their enlistments were up; this was a U.S. Army operation, and Gillem was leaving nothing to chance.

His assault would be two-pronged, and decisive; while Mason’s men attacked from the cover of rocks on the east side of the stronghold, Gillem’s men would attack up the slope again (reinforced boots having been secured from the Presidio in San Francisco, along with the mortars), while a detachment secured the water supply from Kie-ent-poos’ men, thus denying the stronghold any fresh water.

Deprived of water and under constant attack, Gillem was betting that Kie-ent-poos would surrender.

The first of the Coehorn shells began falling on April 14th.

Curley-Headed-Doctor, the Modoc shaman, had participated in a cult which was gaining wide acceptance throughout North America.

Called the “Ghost-Dance”, this was a sub-cult of native American beliefs; participants in the Ghost Dance were said to be immune from the white-man’s weapons. Curley-Headed-Doctor had introduced the Ghost-Dance ritual to the Modocs, and they were of the belief that they could not be harmed in battle.

The first of the mortar shells killed a woman and two small children, destroying the Modoc’s belief in the Ghost-Dance cult, and undermining Kie-ent-poos’ authority over the 175-odd Modocs left in the stronghold. Kie-ent-poos did not have to tell his people any longer that this would be a fight to the end; the continued crump of mortar-fire in the distance, followed by the scream of jagged metal through the air of exploding mortar-rounds told that tale all too well.

For twenty-four hours, round-the-clock bombardment of the Stronghold had not produced one casualty among the men; the only casualties remained the one woman and two children initially killed by the first shells. The lava-caves, while crowded and cold, provided the best natural shelter from mortar-fire.

Kie-ent-poos waited. He knew that the mortar-fire would have to stop before an assault.

On April 15th, Gillem ordered his men up under cover of nightfall to nearly the same positions they’d reached during the January assault. This time, they made makeshift rock-walls from the lava which was to-hand; they waited for dawn.

(Dismounted Federal Cavalry in rocks – Modoc War)

Near dawn, a soldier accidentally discharged his rifle, and Kie-ent-poos knew that the soldiers were nearby, and awaiting orders to attack. It was about this time that the mortar-fire stopped, and he put his Modocs in position to repel the Army regulars who’d been sent to drive him from the stronghold.

The first day’s fighting saw some Modoc snipers and pickets displaced to the main stronghold, but no casualties amongst the Modocs. Several soldiers were killed by Modoc rifle-fire from the stronghold; Gillem ordered his field-commander, Captain Green, to have the men dig in as best they could behind their rock-walls and wait for morning. Twenty-three soldiers were dead (around 8% of their effectives).

On the morning of April 16th, Gillem and Mason ordered a cautious advance.

Reaching the plateau of the stronghold, they were met by desultory fire from some aging Modoc men, who quickly surrendered.

The other Modocs were gone.

Contemporary Army reports, when studied over 100 years later, are a study in blame-placing. Where had the Modocs gone? How had 175-odd people, mostly civilians, managed to escape in the middle of the night through Army picket-lines? Blame was placed on native American scouts; the weather; the terrain – but it was a simple fact that the Army hadn’t counted on the resourcefulness of Kie-ent-poos and his band.

The Army had won – they’d occupied a barren stretch of lava, captured a handful of cattle, a few old men – and nothing else.

Gillem immediately sent out patrols to determine where the Modocs had gone. His efforts yielded no results. Gillem camped the men in the stronghold, and continued to send out patrols.

On April 21st, two scouts reported that there were Modocs sighted four miles south of the stronghold hear Hardin’s Butte. Gillem immediately dispatched a patrol to intercept these Modocs, and to determine if Hardin’s Butte could be used for observation and artillery.

(Hardin’s Butte – Modoc War)

The main patrol, under Captain Evan Thomas of the 4th Artillery and Lieutenant Thomas Wright of the 12th Infantry consisted of 68 men. Thomas was the son of the Adjutant-General of the U.S. Army, Lorenzo Thomas. Two of Thomas’ officers were sons of prominent Army generals – none had experience fighting the kind of guerrilla war which was the province of Indian fighting. Thomas kept his men in a compact column, and failed to deploy ‘flankers and skirmishers’ (men on the flanks and ahead of his column, whose job was to seek early contact with any enemy and to prevent ambush).

It took the entire morning to cover the four miles between the Stronghold and Hardin’s Butte. As Thomas called for a break, and as his men were taking off their boots and sitting down to their rations, withering gunfire broke out from the top of Hardin’s Butte.

Caught literally with their boots off and sitting down, Thomas’ men could do little else but die. While they attempted to deploy up the butte toward their attackers, their casualties rapidly mounted in the face of accurate Modoc rifle-fire; again, the stink of blood added to the smell of the lava and the reek of powder from the panic-fire of Thomas’ men.

In 45 minutes of savage, one-sided fighting, Thomas and Wright were both dead, along with 2/3rds of their joint-command (45 men total). Just as suddenly as it started, the firing from the butte stopped. The moaning of the wounded was shouted-down by the voice of Scarface Charley – in halting English, he said, “All you boys what ain’t dead better go on home. We no want kill you all in one day!”

Thomas’ remaining men needed no encouragement. The march which had taken them four hours over lava took them one hour to retrace, as they ran, stumbled, and crawled from the scene of the Battle of Hardin’s Butte.

It took them until April 28th to return to Hardin’s Butte to retrieve their dead for burial.

Gillem was replaced not long after by Colonel Jefferson C. Davis of the 23rd U.S. Infantry. Davis put together cavalry patrols to cover as much country as possible, with the aim of tracking down the Modocs and bringing them to heel as quickly as possible.

One of these patrols encountered the main band of Modocs on May 10th at Dry Lake, southeast of Hardin’s Butte. During the skirmish that followed, one Modoc was killed, but the Cavalry troopers suffered no casualties themselves, holding on in good order in spite of being surprised by the Modoc war party.

At this time, Hooker Jim’s band, which had quarreled with Kie-ent-poos, left the main band of Modocs and headed north. They were rapidly surrounded and picked up by one of Davis’ cavalry patrols not far from Dry Lake on May 22nd, 1873.

Hooker Jim and several of his men, to save themselves from hanging over the Canby affair, offered to track down Kie-ent-poos and the rest of the Modocs.

(Kie-ent-poos; photographed just before his hanging; October, 1873)

Hooker Jim led several units of U.S. Cavalry and Army regulars to a spot near Clear Lake, where Kie-ent-poos and the ragged remains of his Modoc band were camped. Learning that their position was hopeless, Kie-Ent-Poos, still wearing the uniform-jacket of the dead General Canby (complete with medals), surrendered to elements of the U.S. Cavalry.

The Modoc War was over.

Kie-ent-poos was around thirty years old at the time of his capture. At no time during the course of the conflict did he command more than 53 fighting-age male participants, losing only 13 of his band; seven being noncombatants. He had fought four engagements against 675 well-armed Federal infantry and cavalry, including two howitzers and two mortars, inflicting over 100 casualties.

One Hundred Ponies

“I have a bad heart about those murders. I have got but a few men and I don’t see how I can give them up [to be hanged]. Will they [the commissioners] give up their people who murdered my people while they were asleep?”

— Kie-ent-poos; during his trial

On October 1st, 1873, Captain Jack (as Kie-ent-poos was known to the U.S. Government), Boston Charley, Black Jim and Schonchin John were led into the crisp early-fall air from their airless cells at Fort Klamath, Oregon. The thirteen steps to the gallows were a foregone conclusion; their trial (by a U.S. Army Military Commission), while not a farce, was a far cry from justice.

Standing on the gallows-trap, the hangman carefully adjusted a rope around Kie-ent-poos’ neck. A U.S. Army chaplain asked him in his turn if he wanted to go to heaven. Captain Jack/Kie-ent-poos asked the chaplain to describe this ‘heaven’. The chaplain stated that ‘heaven’ was a place where he could go to ‘be with god’ after he died.

Kie-ent-poos replied, “If this heaven is such a wonderful land,” he said, “I will give your family one hundred ponies, and you may stand here in my place.”

Kie-ent-poos and the others were hanged shortly afterward.

The remainder of the Modocs – -now, around 155, minus those who had surrendered earlier – were sent to a reservation consisting of 5.75 largely-barren square miles near the Quapaw Indian Agency in Oklahoma. Confinement, disease and malnutrition did the rest.

Epilogue:

In the early 1900’s, in exchange for a little over $500,000, the last ‘chief’ of the Klamaths sold the tribal lands of the Klamath and Modoc tribes. The payment was less than a dollar an acre.

In 1909, less than a dozen Modoc were given permission to return to the upper Klamath reservation.

In 1945, the same Klamath chief went to Washington to support a bill which, in effect, ‘liquidated’ the Klamath and Modoc tribes in the eyes of the Federal government.

Acknowledgments and Reference Reading:

This article would not have been possible without the following books, materials and publications:

“Hell With The Fire Out – a History of The Modoc War” – (Arthur Quinn; Faber and Faber Publishing; 1998)

“The Modoc War – History and Topography” – (Thompson; National Park Service Publications; 1971)

“The Indian History of the Modoc War” – (Riddle; Stackpole Books/Frontier Classics; 1914 [reissued 2004])

National Park Service Publications (various; 1979-2004)

Oregon Historical Society; Harper’s Weekly (photography)

Modoc Naming Conventions and General History:The overall history of the Modoc people is difficult to reconstruct, due to the few remaining Modoc and the oral traditions which were not recorded at all by their white opponents, and which were difficult to retain during their diaspora. Pronunciation of Modoc lingual-constructs is problematic to English-speaking people; to that end, many of the only known ‘names’ of the principal Modocs are those ‘given’ them by English-speaking people. Kie-ent-poos’ name comes down to us as he was the chief of the Modocs and the architect of the resistance. Many whites called him “Captain Jack”; toward the end of this narrative, I have used this name only as a reference-point during his trial and subsequent execution.

Canby and Custer: General Canby was a regular-Army general-officer. G.A. Custer had been temporarily promoted to that rank (it’s called a ‘brevet’ rank) during the Civil War; while he often wrote and signed correspondance with his ‘brevet’ rank even after he had been reverted to his permanent rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, Custer was not a general during the Indian Wars. When he was killed at the Little Big Horn, he was a permanent Lieutenant-Colonel.

‘Brevet’ ranks were often issued by the U.S. Army to fill the gap between what was available and what was needed from a human-resource standpoint. This practice was stopped during the Spanish-American War, and has never been reinstituted.

Meacham and Odeneal: Meacham was replaced by Odeneal as Indian Affairs commissioner for the likely reason that he was simply more in-tune with the ideas of the Federal government regarding the Indian ‘question’. Meacham was actually a forward-thinking man for his time, and could likely have defused the entire problem very early on if allowed to do so.

Assassination of General Canby:Much has been made of ‘why’, regarding Kie-ent-poos’ assassination of General Canby. I believe it can be chalked up to his age – he was in his early thirties at the time, and had never seen real combat, much less a political crisis of this magnitude.

The Lava Beds National Monument: This monument was created largely out of the vision of a handful of people who believed in preserving the place as well as the history. Thanks to the climate, much of what was there during the war still exists — the revetments built by the Army troops out of lava-rock near the stronghold, the howitzer and mortar-placements, plus the Army corral and other structures are still plainly visible. Bones are still visible in the Modoc ‘corral’ within the stronghold; a sharp eye can still see riccochet-marks within the Modoc trenchlines.

(I can’t emphasize enough the vista which awaits a visitor to the Lava Beds — the stronghold itself is little more than a lava plateau, about 150yds across. Access in every direction requires a 200yd walk up a six-degree slope, with the plateau at the top. The plateau is not flat, however – although it looks that way from the base. It’s full of the previously-mentioned interlocking trench-lines, natural deadfalls, and caves. You get a small idea of why it took the Army nearly six months to dislodge the Modocs when touring the place.

The Modoc Tribe : The Modoc were officially ‘re-recognized’ as a people by the U.S. Government in 1978, after years of requests from those who remained. Today, the Modoc are split between the new Klamath reservation in Oregon, and the Quapaw reservation in Oklahoma to which they were sent in 1873. The Quapaw band number around 200, and are all direct descendants of the survivors of the Modoc War.

Hiking the Stronghold and Hardin’s Butte: Hiking the stronghold isn’t for the faint of heart – this is forbidding country, and while I’ve hiked most of the battlefield, it’s truly exhausting work. For most people, Hardin’s Butte is an all-day affair in the summertime; taking double-canteens is HIGHLY recommended due to the unvailability of any kind of water nearby.

If you do decide to hike to Hardin’s Butte, you’ll be rewarded not just with a magnificent vista of the lava beds and surrounding countryside, but if you’ve a sharp eye you might just find one of the elusive Springfield cartridge-cases from the battle there. (Note: Removing artifacts is not permitted; you must turn them in at the visitor’s center).

Will, thank you for this detailed account of American history I knew very little about.

Reading it I found it difficult to judge the actions of either people. Differences in culture, beliefs and a certain naive arrogance on the part of “civilized” white people who knew no better in some ways exonerates their actions.

The sad thing is that today we’re repeating the same mistakes and demonstrating the same lack of respect and arrogance toward people whose culture and belief systems differ from our own. We may not be taking colonizing their land, but we are economic colonists nonetheless and displacing indigenous people just as effectively.

Sadly, we are destined to repeat past mistakes. We may have made technological advancement, but as sentient beings we haven’t really evolved much past the point of barbarity at all. Man’s inhumanity to man is as evident today as it was in day of the Modoc.

Great piece Will! Very pro, very detailed history. Great to see history pieces with heart and giving attention to native americans. Damned true conclusion at that.

Mila; Mitch — thanks for your commentary and support.

In truth, this story should be a feature film – it’s got everything, when you stop and think about it. It’s better than the story of the Alamo (with apologies to my Texas friends); the statistics were certainly more lopsided – the terrain is even more inhospitable; it truly does look like Hell; with the fire out.

-W

You’re right, it would make an excellent feature film.

So? What are you waiting for? *grin*

You’ve done the research… now… write the film script!

[quote=W.D. Noble]In truth, this story should be a feature film – it’s got everything, when you stop and think about it. It’s better than the story of the Alamo (with apologies to my Texas friends); the statistics were certainly more lopsided – the terrain is even more inhospitable; it truly does look like Hell; with the fire out.[/quote]

Actually, I’d say that the two battles are more or less equal – yes the Alamo defenders didn’t have to contend with terrain as much the Modoc did, but their numbers weren’t significanty different (about 200 defenders of the Alamo to about 300 Modoc) yet the Alamo defenders faced a far larger opponent (over 2,000 Mexican troops) and were cornered (the Modoc had at least a few opportunities to run).

Disclosure: I happen to live in Texas, so I might have a small amount of bias in favor of the Alamo defenders on account of that…

When you compare the Alamo to the Modocs, you have two very polarized views; on the one side, you have US Colonialism pushing South and Mexico resisting; on the other, you have the US pushing North and the Native Americans resisting. Both are the effects of centralized cultural clashes.

Malice, dear rainbow sister, proof that a sound can be heard around the world, i find this point in time very poignant; the last great conquest of American Colonialism for domination. From that point on, you read about very few clashes between settlers and the indigenous people. The twists and turns of history become very curious, as we’ll try to illustrate over the coming weeks in our coverages of Arctic Rim populations.

Will, i’m very excited about your piece and feel it’s one that will “grow legs”, as you like to say. The academic presentation was exemplary, and one that will help us put together the pieces of a history that is seldom talked about, yet is so crucially a part of who we are today. The Modoc wars aren’t actually the end, but the beginning of a saga that Malice so accurately perceived, continues to be a pertinent issue.

Great historical view of this event Will. I am familiar with the lava beds and the Tule Lake area from our many trips between Yuma and the Tillamook coast, but never knew this story. It is too bad that we had two old Civil War Generals as President and Commandent of the Army; the Indian Affairs agent Meacham, as you said would have been able to solve the problem easily.

Was it Chief Red Scout of the Oglala Sioux who said, “The white man made us many promises, more than I can remember, but they kept just one; they promised to take our land, and they took it.”?

Bill, it should cause shame for a lot of Americans that they have to be taught their history by an East Indian dentist, but in this case it’s a fact – that quote is accurate, and while it’s the product of an anonymous Sioux elder, it’s still true.

(Another which I’ve always found ironic was from an Athabaskan chief who, as he lay dying from a bullet wound – “Your great-grandchildren will rise up and curse you. They will be like us.” This was in the 1870’s. I’ve thought of that from time to time when reading the history of the hippie-movement in America.)

-W

[…] universityofcalifornia.edu/browse/azBrowse/Modoc+War. E-mail Jonathan L. Fischer ¢ Follow …Hell With The Fire Out (A History of the Modoc War)An online magazine offering an alternative, subversive perspective to mainstream media. … By this […]

Say, you got a nice blog post. Really Great.

using this as my essay. tankzz<33

The picture used on this web page to depict a Modoc warrior using a military rifle has been proven to in fact to have been a Warm Springs Indian scout. The military used Warm Springs Indian scouts to help them track down Capyain Jack and his band of Modoc people.