Jingle Bells, played the tune from somewhere, in BoneyM’s revoltingly sweet tones,

Jingle bells, Jingle bells, jingle all the way

Oh what fun it is to ride

On a one-horse open sleigh.

“Dad?” His son’s voice, trembling on the verge of panic. “Dad?” There’s another one.”

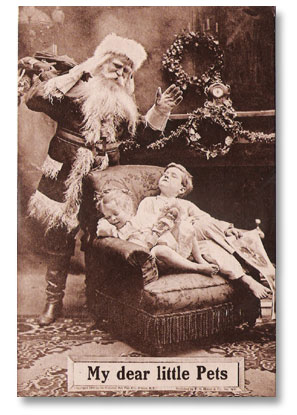

“Don’t look at them, Davey.” He fought down his irritation. He needed to make allowances for the boy’s phobia – god knew he had to make allowances for a lot of things – but this was beginning to get to him. This time of year, one didn’t even have to step out of doors to encounter them. One only had to turn on the TV or open the newspaper. They were everywhere.

But it wasn’t the ones in the papers or on TV that frightened his son, it was the ones on the street corners and in the stores. One couldn’t take him anywhere without panic attacks but one couldn’t leave him alone at home either. Sean gritted his teeth and resisted the urge to crush the boy’s hand in his own, to cause pain and tears. “Don’t look at him.”

“But he’s looking at me, Dad.” The boy’s voice, now perilously close to the familiar wail. “He’s looking at me!”

“Nobody said you have to look back, did they?” But he took the boy’s hand and pulled him round so now he was between David and the object of his fear. He smiled apologetically at the fat man across the street; the fat man looked back and smiled benevolently. “He’s smiling at you, Davey,” he said, but the boy only tugged harder at his hand. “Dad?” let’s go, please?”

“All right, Davey.” He tried his best to keep hold of his temper, but it was difficult. His son needed to be helped, he often thought. It wasn’t easy for the kid either, having to live with a father he had virtually never seen till just half a year ago. It wasn’t easy coping with the trauma of the loss of his mother, almost before his very eyes; and now this phobia.

He remembered the last time he had talked to Phoebe over the phone. He hadn’t seen her then in well over a year, since after the divorce. He had sent her a cheque every month and that was it. But his conscience had been pricking him after he listened to the others in the mess hall talking about their kids growing up without them, so he had finally phoned. Phoebe had been surprised to get his call, surprised and not wholly pleased. He had sensed the coolness right through the static of the really pretty bad connection. She had said, yes, the boy was fine, and no, he couldn’t come to the phone and talk because he was sleeping. It had seemed a bit odd that he would be sleeping then, so early in the evening Phoebe’s time, but he had let it go. He had not thought it worth phoning again.

But Phoebe was dead now, victim in her own home of some psychopath so sadistic that when they had found her she could barely be recognized any more as a human being. The madman had never been caught. And Davey, who had been in the house at the time and slept through it all, was now his charge – along with the responsibility of making a new life after a decade and a half, all his working life, in the army.

Poor kid. faced with the sudden loss of the mother who was all he had ever known as family in the five short years of his life, forced to live with a father who was not only a stranger but had certainly been blamed by Phoebe (being who she was) for everything that had ever gone wrong (like “You can’t have that toy because I have no money and that’s because your dad is such a bastard”), he must feel like a prisoner of war. And on top of that he had all this fear – of darkness and of closed spaces and of this and that and whatnot. A fear, of all things, of Santa Claus.

He should have left the army long ago, he knew. If he had left early enough, Phoebe and he might still be married. The boy might be growing up as a normal kid. But soldiering was all he knew, and it was not easy to decide to throw away an entire career, after making Colour Sergeant Major, just because his wife was not happy with him being away so often and so long. But he had had the stubbornness in him too, and once she had left there was no further point even thinking of leaving. He probably would have been in the army now, Phoebe or no Phoebe, but for the Taliban rocket-propelled grenade that had left his right foot a shattered stump. He had just been discharged from hospital, artificial foot and all, when the news about Phoebe had come. And after that he had been given a medical discharge anyway.

The snow had begun to fall again, thin and drifting, from a sky the color of slate. Sean turned up the collar of his coat and pulled the boy’s conical woolen cap down over his ears. He saw another street-corner Santa ahead and cursed silently. If he had seen the man in time he would have taken the boy by a side street. But then in the side street you’d probably find another Santa there too, especially now, three days before Christmas.

Besides, how long could you feed a phobia? At some stage the boy had to learn to face his fears. Yes, but, he cautioned himself, not all at once. Go slow.

He could feel David tense up all the way through the boy’s hand and his glove. This time it was worse because this Santa was on this side of the street. For a moment he considered taking the boy across and re-crossing, but that would have been really too ridiculous. Besides, the entrance of the store was only just beyond the Santa, so if they went across the street they would just have to come right back again.

“Ho ho ho,” said the Santa, and tolled his ridiculous bell. He beamed at them, a fat red man in a white beard. This was bad enough. But he was fatter than the last Santa, and redder, and more jovial, and that made things much worse, because the boy was more frightened by fat red Santas than by thinner and paler and more morose ones.

“Dad -“

“It’s all right, Davey.” He dropped a note at random into the Santa’s little plastic chimney and smiled. “Sorry,” he said, almost pulled off balance by the boy’s frantic tugging. “He gets a little nervous –“

The Santa smiled widely. His teeth were discolored. He shook his head a little side to side and was still tolling his bell when they entered the store.

It was easy enough to see the Santa in the store, with his line of children, and easy to avoid that section though a smiling store assistant tried to usher them that way. “We’ll be all right,” he said, and took David up the escalator to the real shopping section.

Later, he phoned his oldest remaining friend from the days before the army. The friend was a psychiatrist, bald and portly and suffering from high blood pressure and incipient diabetes, but he was still a friend.

“So,” said the friend, across the hundred-odd kilometers of snowing darkness between them, “and you haven’t noticed this before?”

“How could I? I’ve only had him since January. You see many Santas around in January?”

“His mother didn’t mention it?”

“His mother didn’t mention anything to me. His mother didn’t talk to me if she could avoid it.”

“Ah. And he’s scared of Santa, and what else? Only Santa?”

“Hell. Santa and darkness and being alone and I expect every day to find something new he’s scared of. “He looked out of the window at the darkness. Snow floated down in the light, glinting momentarily. “I don’t know what he’s scared of.”

“When did you first notice he was scared of Santa?”

“Early this month.” they had gone out to the store and he had seen the Santa there, and there was as yet no line of kids standing in front of the Santa, so he had taken the boy along and walked over, thinking to give him a little treat. But the shivering had started right then, shivering so intense he had felt it all the way in his own shoulder. He had turned and seen the boy’s face, white and sweating. “Dad…no.”

“Davey? What’s wrong?” he had crouched down and looked the boy in the eyes, with alarm and puzzlement. It had seemed to him that his son was about to faint. “Davey?”

“I can’t…not him; Not Santa…Closs.”

“He said Closs?” asked the psychiatrist. “Not Claus, Closs?”

“How does it matter? Closs, Clause, whatever. His teeth were chattering all over the place.” Sean had fought down his irritation long enough to take the boy away from the Santa, who had been staring at them with some puzzlement. Later he had asked the boy what had bothered him, but he had only shaken his head and refused to speak.

“And then one time he was watching a TV programe where Santa was coming down the chimney – you know, one of those kid’s flicks – and he began hyperventilating and screaming something about the chimney. I had to shut off the TV. Most of the time he’s pretty good about the TV though. He’s much more scared of real-life Santas.”

“You have a chimney?”

“All the old houses in this town have chimneys. Not that they are used, most of them. Mine isn’t.”

“Is your son scared of the chimney?”

“He hasn’t mentioned it since. But I don’t know what he thinks inside his head.”

“And before this his mother had been killed, last December? What happened there?”

“I don’t know the details. Some psycho entered the house at night and slaughtered her, a couple of days before Christmas. Left her, just about turned inside out. The neighbor found her the next morning. He, Davey, was still sleeping.”

“Um… It must have been traumatic. Maybe he associated Santa with his mother’s death. It happens sometimes.”

“So what’s the way forward?”

“You can’t possibly take him to a country where there is no Santa till Christmas is over? Saudi Arabia or somewhere like that?” The psychiatrist answered himself. “I guess not. Look, Sean, I’d like you to bring him to me tomorrow. Come early and you can stay the night. I’ll observe him.”

“All right.” he could adjust his time. He still had no regular job and the pension was still paying the bills. “I’ll be coming.” In the car, taken out after so long, driving carefully not only because of the snow but because his right foot was fake and could so easily slip off the accelerator – or press down hard. He’d see. Christmas traffic. Snow and ice. A metal foot. A kid who was a shivering neurotic and who more probably than not looked on him – his dad – as his jailer. What a mess.

He looked in on the boy in his room. He was sleeping, the night light on, his thumb in his mouth. He looked at the boy and then he went to bed.

He woke in the middle of a dream, one of those dreams that were so real that they were not distinguishable from reality, only this had not been a dream once. He had been riding shotgun at the head of the convoy, scanning the brown dusty hills on either side for the enemy, the driver in the right hand seat hunched forward over the wheel, studying the road for signs of a buried mine, and still going as fast as he could. It had been a very quiet day apart from the noise of engines. They had not even seen the occasional farmer in turban or Afghan pakol. And that was strange, but he had shrugged off the strangeness, because he was going on leave at the end of this trip. He could almost taste the beer.

Then it was that the Taliban had sprung their ambush and the first RPG had slammed into the door on the driver’s side, smashed through and exploded, reducing the driver to chunks of bloody flesh and apart from a brief confused moment of blood and pain he had known nothing more until he had woken up in the hospital.

It was the same in the dream, only he had been in the shotgun seat, knowing the ambush was coming, anticipating it, but unable to do anything about it, waiting for the tongue of flame and the explosion, the thread of tension stretching until it had to break – but it did not. He snapped awake.

Dimly, he realized that the darkness was much greater than it should have been, and it was colder. The lights from the street were still entering through the top of the high window, but the little glow from the thermostat was off. He reached out for the table lamp. As he expected, the lights were out.

Damn. If there was a blown fuse in the mains, he’d better do something about it before they all froze. And if the boy woke and found himself in the dark, he’d start screaming the house down. If there was any way he could get the lights working, he’d better get on with it.

He took the torch from the bedside drawer by touch and turned it on. The light was fitful and dim – worn out batteries. But there was enough to see by. He moved quietly to the door, shuffling in house slippers, and moved downstairs to the living room. On the way he paused outside his son’s door. The door was slightly ajar so he closed it. There was no sound from inside. The boy hadn’t woken yet.

Down in the living room it was very cold. He skirted the sofa across the room from the fireplace and went down to the basement. The torch lit up the circuits, but the fuses were all intact. Damn again. Maybe the snow had taken down some power line somewhere. He shut the box and went back up. The torch was so weak now he could only see the floor right in front of him.

That’s why he almost stumbled on the boy before he saw him.

The boy lay on his back, arms and legs spread wide, head thrown back. The centre of his body was one huge gaping red wound. Shards of bone mixed with blood that was still running. Steam rose from looping coils of entrails.

He stepped back, the torch falling from his hand, a shriek tearing at his throat. “Not Santa Closs,” a voice yammered inside his head. “Not Closs, not Clause. He didn’t sleep through the murder after all. Santa Claws, that’s what he was saying. Santa Claws.”

In the darkness of the fireplace, something began to move.

That was one sick husband to have had! 🙁 The boy must have been seen it coming I guess!

WOW! : ))

Gruesomely appropriate. Happy Holidays Bill!

Totally gross! Had me captivated the entire time. Those damn fat guys in the red suits. Thanks for the tale.

Now Santa Claus has taken on the same evil appearance as deceptive clowns. Poor kids. They’re going to start trembling at everyone who wears a mask. Very well written, by the way. It gave me a good shudder.