The Hegelian Dialectic

Mexico is at war. The violence has escalated enough that in mid-October of this year, U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice traveled to Puerto Vallarta to meet with her Mexican counterpart, Patricia Espinosa. Their appraisal was that the violence was due to the rising feuds between drug cartels, making national security a priority for both countries. A recent grenade attack in Morelia during the height of a September workers’ celebration killed eight bystanders and injured 100, raising the death toll from drug violence this year to more than 3,700.

According to an October 25th coverage in Newsweek, the escalated violence is a reaction to President Felipe Calderón’s aggressive moves against the cartels. When he came to power in 2006, he needed “a signature issue that would make him look strong,” says Shannon O’Neil, a Mexico expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, and announced he would use federal troops to target narcotraffickers. He argued that the offensive would reduce drug-related violence and weaken the influence of drug cartels. But as the body count climbed upward, Calderon’s strategy shifted. The military surge had turned into a war to eradicate the drug trade—something most experts agree is nearly impossible. Bodies have been piling up ever since. In 2006, between 1,500 and 2,000 people were killed; this year the toll is already at 3,725.

Calderon’s signature issue has overlooked many of the causes for Mexico’s political unrest and calls upon an expediency of law that only exacerbates the conditions of unhappiness. The Human Rights Committee in Mexico City, wrote an open letter to President Calderon, sharing some observations regarding the justice reform package that was approved by the Mexican Congress. Of particular concern to the organizers was the proposal to modify article 16 of the Mexican Constitution to allow prosecutors, with judicial authorization, to detain individuals suspected of participating in organized crime before they are charged with a crime. This pre-charge detention would be possible for a period of up to 40 days if “it is necessary for the success of the investigation, to protect individuals or goods, or when there is a justified risk of flight.” The 40-day limit could be extended for up to an additional 40 days if the circumstances that gave rise to it continue to exist.

The committee purports that this proposed 80-day limit would be, by far, the longest of its kind in any Western democracy. In other countries, the limit for any form of pre-charge detention, or preventative detention, is generally less than seven days. In the context of combating terrorism, for example, the maximum period allowed for pre-charge detention in Canada is one day; in the United States, Germany and South Africa it is two days; in Italy and Spain it is five days; and in Ireland and Turkey it is seven days. The United Kingdom recently extended the time limit for pre-charge detention for certain terrorism related offenses to 28 days, making it the Western democracy with the longest pre-charge detention time. However, British courts have yet to adjudicate on whether this is consistent with human rights law, although previous case law indicates that such a long pre-charge detention period is not permitted.

A second provision in the new Constitution would remove from the judges the power to decide, in cases involving one of a prescribed list of offenses, whether a defendant should remain in jail or be provisionally released pending and during trial. Although the Constitution propounds innocense until proven guilty, the alterations would grant an arbitrary means of prolonged detention without the obligation of criminal charges.

The Policies of War

President Filipe Calderon was already facing a country in turmoil when he took over the reigns of running the country of Mexico. The oil industry, which has maintained a stability in Mexico’s economics for years, is floundering. Maintaining a policy of processing its own oil, Mexico no longer has enough reserves for selling oil in foreign markets, pulling out as the second highest provider next to Canada in sales to the US industry. Their only recourse is in off shore dwelling. They don’t have the technology for this type of development, and have been forced to write a new resource development policy of lease sales in order to entice foreign investors.

Ten years of introducing Capitalist free enterprise has not improved the conditions of Mexico’s fifty million poor. In a move to protest the number of McDonald’s, Walmarts and other foreign corporate chains that have monopolized Mexican business interests, the working class organized and petitioned for “a day without gringos”. For one day a year, they would refuse to patronize any business whose investment came from foreign soil. Seeking the popular vote, many governors of state enthusiastically joined this venture that calls for a boycott on American schools, goods and stores. However, it’s very difficult to measure the impact of this strategy on foreign investment as after receiving state support, the day officially mandated was for May Day, a holiday that had already been set aside as a worker’s celebration.

The price of a five percent annual inflation rate has had a shocking effect on the Mexican populace. Even though a freeze has been placed on certain pantry items and goods, the overall impact has been so high, many working Mexicans have been without enough funds to adequately feed, shelter and clothe their families. The problem has been especially evident in the state of Oaxaca, historically Mexico’s poorest region, where thousands of people have migrated into the United States in an attempt to end their poverty.

For the first time in eighty years, a candidate was voted into the highest office from PAN; the National Action Party, instead of the historically dominant Institutional Revolutionary Party. PRI places the blame for its defeat on a fracturing within party loyalties. Lopez Obrador rose to the forefront as Calderon’s leading contender under his own party banner, the National Democratic Convention. For the first time in modern history, Mexico has three political parties struggling for dominance.

The Legitimate President

Calderon won the election by a slim fifty-one percent of the vote. Obrador claims the election was won by intimidation and fraud. His supporters continue to wield an offensive against the ruling government. What began as a simple teacher’s strike at the beginning of Calderon’s tenure, quickly turned into a conflict of such grave proportions, the incumbent President, Vicinte Fox, was asked to serve as mediator.

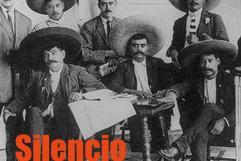

Oaxaca City was no stranger to seize. In 1985, Mexico’s Revolutionary Party set up camp directly across from the palace headquarters, and retained their position throughout the years, up to and during the uprising that resulted in a coup by Calderon’s government. News during the 2006 action against the city of Oaxaca was scanty and desperate. From May to November 2006, a coalition of striking teachers and leftist supporters blockaded the city to demand the resignation of the state governor, driving out tourists and paralyzing traffic, commerce and tourism.

Witnesses spoke of a military invasion of 5,000 that had been labeled a police force and included helicopters and tanks. Citizens were unduly harassed and attacked. Protestors were jailed or murdered. Their last pleas were to humanitarian committee’s in which they declared they had no food, no water, and feared each day for their lives. Telephone lines had been cut and there was only one remaining radio station. Then there was silence.

The political divisions remain, but the violence has died out, at least for now. Most of the graffiti and damage has since been removed or repaired. The striking teachers got some of the pay raises they demanded, but their leftist allies got little: about a half-dozen protest leaders remain jailed. The unpopular Gov. Ulises Ruiz, who was accused of being responsible for the death of 52-year-old Lorenzo Cervantes when a convoy of armed gunmen opened fire on the protesterś camp outside Radio Ley, remains in office, and little progress has been made in investigating the case of Brad Will, a New York journalist-activist shot to death during the uprising.

Oaxaca City is quiet now. The resistance encampment is gone. The graffiti and slogans have been washed from the walls. Tourists have been encouraged to return, although the ones who remember Oaxaca’s old days, complain that the town has become too contrived and too aesthetic to retain its charm. The street vendors have been removed, along with their colorful trade and system of barter.

The lull in Mexico’s politics is a quasi- peace. The methods of resolution have been ones of violence and repression. Although the drug traffic is just cause for concern; gangland and cartel killings have spilled over on both sides of the border, victimizing innocent civilians and small children in its slaughter; there are many factors involved with Mexico’s unrest. The drug war is a convenience label to divert attention from other, crucial issues and maintain US sympathy for Mexico’s need to build an army. This army doesn’t address Mexico’s poor. It doesn’t address the concerns of its popular leaders. A recent poll found that only 25 percent feel safer because of the surge, with 50 percent unconvinced the strategy will work by the time Calderón leaves office in 2011. Hundreds of documented cases of human-rights abuses committed by soldiers have not helped the government’s case either, drawing into question the wisdom of using federal troops as a police force.

What has been ignited is a war on poverty; a war to stifle the voices of people with legitimate concerns for their families and ability to provide for them. It is a war that is being carried out in every country where economic policy has not helped its people to thrive. It’s the dirtiest war of all.

How sad. A cause where people attempt to make a stand for their civil rights is shut down due to capitalistic take overs and drug trafficking. The governmental militia remains defeated to the drug cartels? I sure hope that the 40 day detention works and makes an overall change. We really are blind to international societal dismay. Damn the Walmarts! Mexian officials are equally to blame for allowing foreign monopolistic empowerment over their own people and small businesses.

Maya, i would examine cautiously any legislated action that infringes upon basic human rights. Up to eighty days without charges isn’t a tool; it’s a weapon. It’s a legal means of holding any person without preamble or probable cause. When such gateways are opened with public approval, we are, once more, surrendering free choice in favor of the illusional policy of safety.

I don’t believe the drug cartels can be detoured through arbitrary confinement any more than i believe you can enforce the peace. There is an immutable law; for every action there is a reaction. The business of drugs has been a profitable one; both in Mexico and in the United States. The beneficiaries don’t include just some wealthy gang lords. It includes politicians, attorneys, police officers and border guards, all taking their cut in the perpetration of the trade. It includes the nation’s addicted as well as the growers, the chemists and the highly professional dealers of drugs. It includes billboard advertising; guilty of dangling unknown delicacies in front of exploring minds. It includes the contradictory statement of “no to drugs” while pushing pharmaceutical companies.

You would have thought by now America would have realized the futility of backing legislative force against a popular recreational drug through its experience with the prohibition era. It didn’t. All it has learned was to accept alcohol as a legal drug. It continues to send millions of dollars each year to other countries to support their military’s supposed war on drugs. These funds are more often than not channeled into a war against its people; the poor, the desperate, the struggling to survive. We close our ears to their pleas because we must take care of our own safety. While the jeopardized few become many, while violent action against them provokes further violent action, our safety net grows smaller, becoming a prison. You might as well wish for Santa Claus to visit you as wish that a bad law will be successful in curbing drugs and ending the violence.

As a country we produce very little and import a great deal. The government prints money and borrows and borrows. The pound collapses (the worst is yet to come). Inflation is inevitable and the only way the government, who borrow in

Hey there! Someone in my Facebook group shared this website with us so I came to look it over. I’m definitely enjoying the information. I’m bookmarking and will be tweeting this to my followers! Excellent blog and superb design and style

[…] the year 2008, Condeleezza Rice visited Mexico to give a hand to President Felipe Calderon’s government in its efforts to reduce […]